CONNECTOR INTERVIEW: PAINTING AND POLITICS BY JODI HAYS

OCT. 19, 2017

CONNECTOR INTERVIEW: PAINTING AND POLITICS BY JODI HAYS

OCT. 19, 2017

I chose to ask four painters about the role politics might play, however broadly, in their practice. The interview with Mark Brosseau, Brian Edmonds, Christina Renfer Vogel, and Donna Woodley is in conjunction with the exhibition, Eyes Like Enemies [at ESPS: East Side Project Space, Nashville, TN]; a show in which I present two painters whose work allows for formal concerns to be “disrupted” by other “informants” like language, history and biography.

No space is apolitical. Each space (including galleries, museums, artist-run spaces and non-profit art spaces) hold a set of knowns, or conditions under which they work — against or with our art ecosystem. These conditions are sets of rules they break or set. I would offer, as well, that these spaces offer their own critical pedagogy. The space that Eyes Like Enemies occupies a temporary space for a temporary space, calling attention to issues of real estate and class.

- Jodi Hays, October 2017

Jodi Hays: How is painting political (as a hopeful act, in the studio, resistance)?

Donna Woodley: Painting can be political in its content and materials. Chris Ofili's The Holy Virgin Mary (1996) is an extremely “political” painting that deals with religion, hip hop culture, and the objectification of women. One of the materials used is elephant dung as claws that uphold the painting. One of my greatest resistances is to not let what other people may think govern what I paint about or allow those thoughts to prevent me from making something that I had in mind to make.

Mark Brosseau: For me, political relates to people, or groups of people, working together for the advancement of the greater good as they perceive it. This involves dialogue with those who both agree and disagree with you, and will almost always involve compromising in order to make any real progress. Somehow now, politics and moral values have become intertwined, much to the detriment of political activities. Instead of focusing on how to reduce suffering and improve the quality of life for the largest number of people possible, we get squawking about what is right and wrong. That isn’t political — that’s proselytizing.

Ideally painting is political in that you are creating a dialogue with your viewer where you will work together to form a better understanding of the questions that drive your practice. This dialogue towards a larger good is a political act. Work that takes something from current events and tries to understand it, tries to explore the root issues involved, and allows for growth of both the artist and the viewer, is always essential, but particularly in tumultuous times like the ones we find ourselves in now. If you are making work seriously, then this dialogue with the viewer is a key component. You should not only feel like you are getting a greater understanding of the questions you’re asking, but that your viewer will have an invitation to begin this conversation with you.

Mark Brosseau in Eyes Like Enemies at ESPS: East Side Project Space (Nashville, TN)

Christina Renfer Vogel: Thinking about politics more broadly, in relationship to power, obviously there are all sorts of dynamics at play — in academia, nonprofits, and museums and in galleries at every level, from artist-run spaces to blue chip mega galleries. There has been progress, but we know there needs to be greater equity, that we are in need of a higher level of representation for women and people of color, from the work being shown to the people who are in leadership positions. At this point in time, I think we all have a responsibility to be conscious of that inequity and to do our part to create more balance in our field. Not everyone considers this a priority, and that baffles me.

As artists, we have a platform to present ideas by overt or subtle means; we can raise questions, provoke, and encourage dialogue. But addressing politics through our work is only one way to be political, and our actions may be more significant; I’m talking about our behavior, the way we treat one another and the way we take action. We can all do the work to create a more equitable and inclusive artistic community, to provide opportunity for others, to promote and support each other, and create change. I hope to contribute to making that kind of space as an educator, and I hope that my students will go out in the world and do their part to think beyond their own self-promotion, to also consider how they can help to build a supportive community and field. It all comes down to relationships and how we treat one another, and so we can make change on a person-to-person level.

Christina Renfer Vogel, Beyond, 2014, oil and acrylic on paper, 22 1/2 x 30 1/8"

Jodi Hays: Do painters have a responsibility to speak about political issues with work? What has been your position? Has it changed? Why/Why not?

Donna Woodley: I believe that painters have a responsibility to speak about whatever is in their minds and hearts to speak about whether it's political or not. That does not mean that they are obligated to speak politically if they do not make generally work with political content. That also doesn't mean that they can't wake up one morning and decide to make work that has political content. My work is centered around mostly socially engaged content. My work can be viewed through a political lens; however, it was not made for the purpose of politics.

Donna Woodley, Kelsheika, 2016, oil on canvas, 30 x 36"

Mark Brosseau: Given my definition of political, what I think is really being asked here is do painters have a responsibility to speak about current events with work? For that question, I would say the answer is ‘no’. In the same way that a scientist or mathematician can pursue research that has little to do with current events, I believe an artist can undertake a practice that has investigation as the root. This doesn’t mean that the artist (or scientist or mathematician) can pretend to exist in a vacuum — it is important to know about what is going on in the world, have discussions about those things, and take appropriate action when one feels called to do so. I just don’t believe that appropriate action ever needs to involve my paintings. I’ve always struggled with this: felt like I was being a coward or shirking some level of responsibility. But, I’m realizing that practices where investigation is the basis for making work are now more important than ever, as the norms of communication shift more and more to shouting but never listening — telling but never asking...

I’ve always been more of a scientist than a story teller. And, I tend to be drawn to work that is more empirical — work that is undertaking an investigation and attempting to contribute to our greater understanding of the universe. For me, a lot of propaganda is forgettable once the message is received. The point of the work is that message, so once that message is communicated, the work has no more purpose going forward. Work born of investigation will invite viewers to be a part of that investigation, pushing the collective understanding forward. There are a small handful of artists who are able to make work that is empirical in nature but can also function as propaganda. Most of this work involves investigating a personal or cultural history where the act of making the work is a way of asking questions about that history and its relevance. Kara Walker, Jacob Lawrence, Kathe Kollwitz, José Clemente Orozco, and Leon Golub are a few that come to mind.

Jacob Lawrence, Barber Shop, 1946

Brian Edmonds: Art can certainly provide social commentary or promote social change. However, I don't think an artist has a responsibility to use their work to speak out about political issues. My position has always been the same, regardless of the political climate. As an artist you have to decide if that is what you want your work to do or say. Sometimes the subject matter chooses you. Regardless, you have to stay true to yourself, not only as a painter but as a human being.

Brian Edmonds in Eyes Like Enemies at ESPS: East Side Project Space (Nashville, TN)

Christina Renfer Vogel: I don’t think painters — or artists in general — have a responsibility per se, but there is certainly an opportunity to engage political issues through our work. We must deeply consider the broader context of our work in relationship to its message and what it means when we put our work out in the world. A thoughtful framework from the curator and/or artist is essential.

Image or text-based painting might seem like the obvious way to deliver a message or take a stand, but painter Tomashi Jackson makes exhilarating, devastating abstraction that is engaging history and addressing what it means to be living in our time. She is just one example.

I do consider my work within the context of making paintings today, through a feminist lens, but I don’t think that’s enough to claim my work as political. I have found that I need to compartmentalize. I strive to be politically active and aware, but I don’t want that to enter into my work in the studio at this time, and I am aware that it is a privileged position to choose that separation.

I have noticed that there is an urgency and anxiety amongst my students in response to the president and his administration like I have not seen before, and more of my students are interested in working through political issues in their work, especially as it relates to identity, due to real feelings of alienation, anger, and fear that is a direct result of the election and its aftermath.

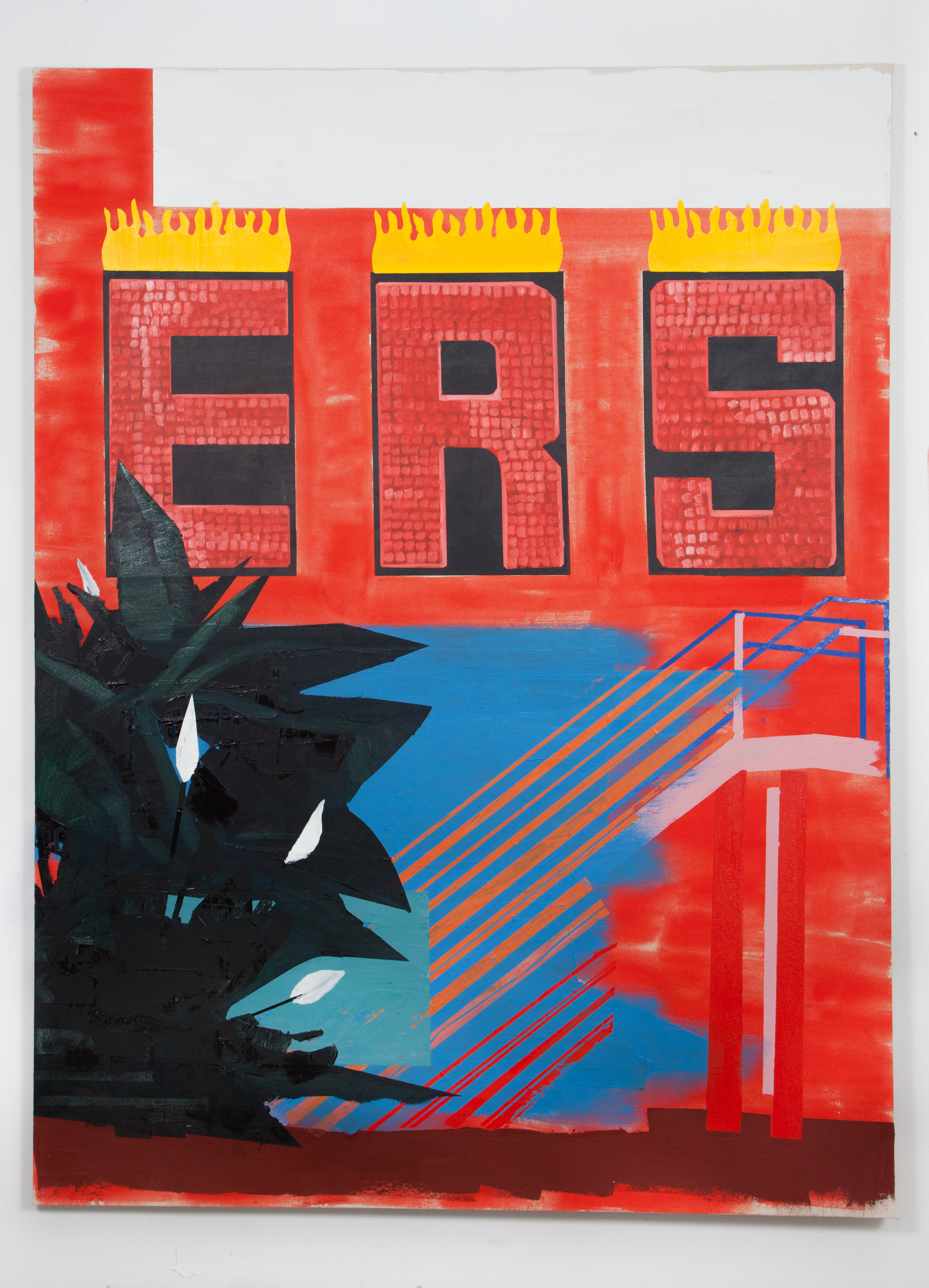

Jodi Hays, ERS (Emergency Recovery System)/Peace Lily, 2017, oil on canvas over panel, 64 x 48"

Jodi Hays is a painter who received her M.F.A from Vermont College, her B.F.A. from The University of Tennessee, and studied Foundations at School of Visual Arts (SVA). She lived and worked as an artist in Boston for a number of years where she was Assistant Director at the Cambridge Art Association. She moved to East Nashville in late 2005, teaching and curating, working with artists like William Pope.L and Shaun Leonardo, to name a few. She maintains a studio and pop-up gallery (Dadu). She was a founding member of Coop Gallery and continues to teach. She shows her work with The Red Arrow Gallery (Nashville) and Show and Tell Art and Design (Charleston, SC).

Donna Woodley is a painter whose most recent works merge the examination of black culture and fine art. She decided to pursue the life goal of a working visual artist after twenty years of working as an accountant. This journey has sparked her passion for painting currently informed by discourse concerning black women and their experiences in American society. She has served as gallery assistant at Tennessee State University’s Hiram Van Gordon gallery in addition to teaching assistant at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts during her undergraduate studies. She resides in Nashville where she is emerging within the art community having participated in a number of group exhibitions.

Mark Brosseau was born and raised in Vermont's Northeast Kingdom, where his desire for discovery was fostered in school through math and science classes, and at home through afternoons exploring the forest that surround his home. He received his BA from Dartmouth and his MFA from the University of Pennsylvania before spending a year painting and making prints in Iceland as a Fulbright Scholar. He lives in Greenville, SC with his wife and two dogs, and is a member of Tiger Strikes Asteroid Los Angeles.

Christina Renfer Vogel holds a MFA from the Massachusetts College of Art and a BFA from Tyler School of Art, Temple University. She has exhibited widely, including recent solo exhibitions at Augsburg College (Minneapolis, MN) and Julia Martin Gallery (Nashville, TN). Christina joined the faculty at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in 2013 where she serves as Assistant Professor of Painting and Drawing.

Brian Edmonds (b.1974) is an artist living in Alabama. His recent shows include The Lost Sea (Huntsville), DUSK: Embossed (Manhattan/Saint Chamas, FR), DO IT YOURSELF (Brooklyn), White Hours (Cyprus) and OFF THE WALL (London). His monoprints are currently available through DUSK editions in Brooklyn, NY. Brian’s work can be found throughout North America and Europe. In 2012, Brian launched the online exhibition space Curating Contemporary. Since its inception the site has hosted over 30 exhibitions. He has also maintained the Curating Contemporary blog during this time. The blog is a source for upcoming exhibitions, studio visits, and interviews he has conducted with artists. Brian’s writings and interviews can be found in the catalogue for Clayton Colvin’s Space Mountain as well as the online journal Figure/Ground Communication.