INTERVIEW: ADAM ROWE

SEP. 21, 2023

INTERVIEW: ADAM ROWE

SEP. 21, 2023

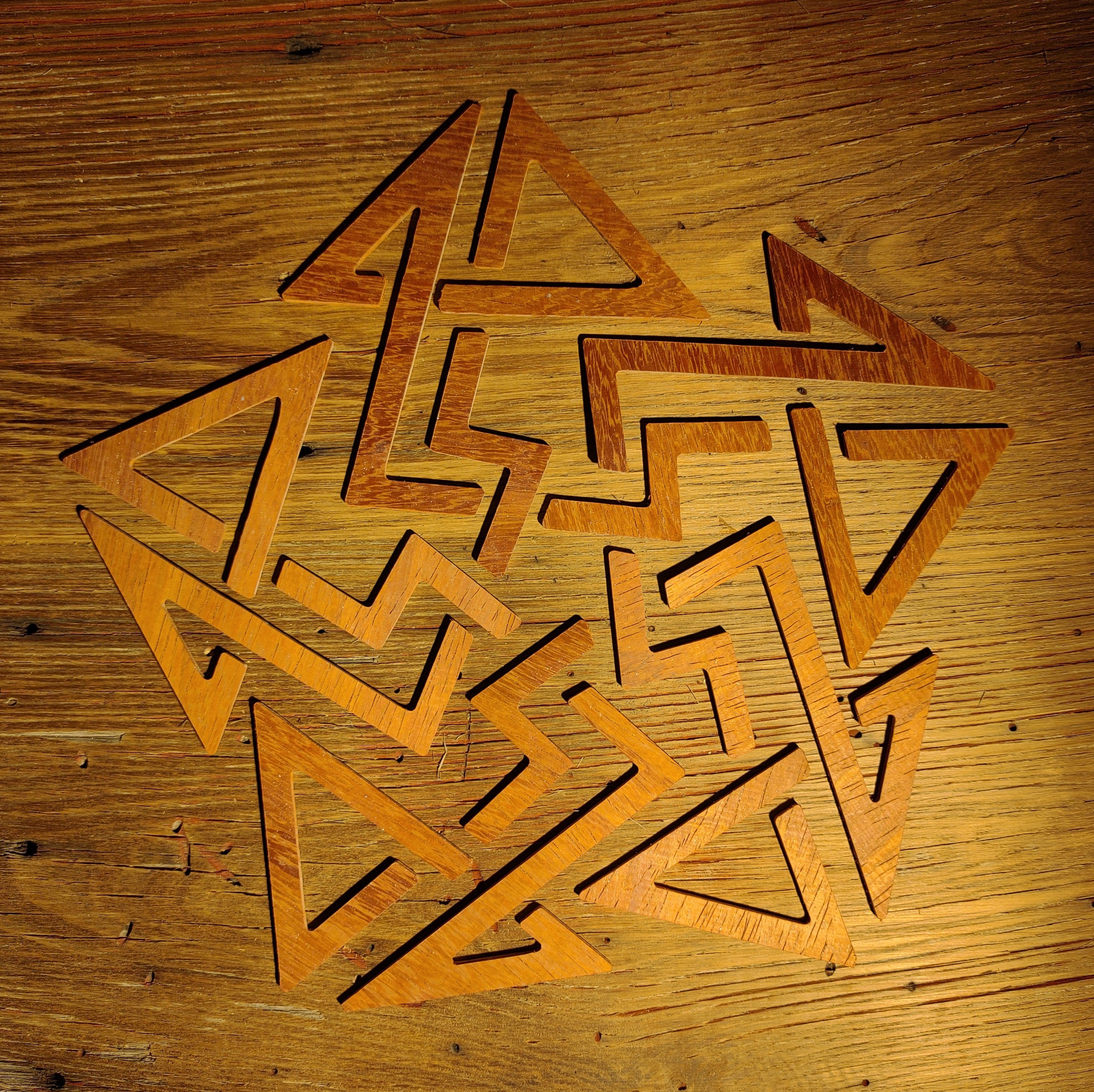

Rachel Bubis: You use a “formalized system of knot creation” in the geometric shapes and patterns of your work. Can you elaborate on what you mean by “knots,” and how you developed this system? Where did your interest with knots begin?

Adam Rowe: Technically I should probably be using the term ‘knot diagrams’ since, generally speaking, a knot is a closed, non-self-intersecting curve embedded in three-dimensional space. That basically means that if you tie any knot you might have heard of by name (e.g. tucker’s hitch, windlass, or your shoelaces) and fuse the ends together, you have something that qualifies as a knot in the realm of math.

Celtic knots (which are also diagrams) have always mystified me: they seem so simple and so complex at the same time. Determined to figure out how they are constructed, I learned that they are made using structured methods. So structured, that there are limits I wanted to play with. For example, you can’t really use Celtic knot design rules to make a pentagonal knot or anything based on an isometric grid. My system only has a few rules, and even though I’ve been using it or a while now, it seems like there is a lot more to explore.

Adam Rowe, "unicursal pentad knot", wood (padauk, barn board), 16.5" square

Adam Rowe, "square tile-based surface-tiling curve listing band (И 3)", steel, dye oxide, 36” ø (approx.)

RB: In addition to visual art, you compose music that incorporates knot systems such as in your piece Legend Three: Knot. Do you consider your visual and sound work of the same practice? Do they inform one another?

AR: Rather than informing one another, I think the idea behind a work of art in any discipline is the real thing – the thing that you make, form, write, cook, etc. – that’s just an instance of an idea. This is easy to understand with music where you have notes on a page which are basically a set of instructions. The performance isn’t the idea; it’s an instance of the idea, and there can be any number of instances.

Sometimes the same basic idea can be realized by multiple disciplines. For the piece you mentioned, the big idea was 'a closed path where the beginning and end could be anywhere.’ This describes knots and it also describes a piece of music which could be listened to starting from any movement and still have a sense of a beginning and an end, even if you start in the middle and loop around to get back where you started.

Adam Rowe, "scale tile listing band", steel, paint, twine, 18” ø listing band

RB: Some of your recent works are part of the Bridges Organization Conference Archives. This organization explores mathematical connections in art, music, architecture, and culture. Can you tell me anything more about it? Do you consider your work to be a type of mathematical study?

AR: Bridges is an amazing organization. It includes people who have made ground-breaking discoveries as well as casual enthusiasts. Reading the archives from past conferences gives you an idea of what it’s all about. You’re guaranteed to come across ideas you’ve never heard of.

M.C. Escher once said, ‘I am an artist, not a mathematician.’ Later in life he also said, ‘I am a mathematician, not an artist.’ I would rather not go to either of those extremes, but I am confident categorizing my work as ‘math art.’ If my work is a mathematical study, it’s definitely a playful one. When I find out about a concept new to me, I feel like I’ve been given instructions for a new type of building block.

RB: You apply principles from your background in graphic design in your current work - can you talk more about this? What type of graphic design did you do?

AR: I always got a lot of satisfaction from finding ways to clearly present ideas. I think of graphic design as a way to use visual elements as a language for this process. Since you’re usually working with constraints of printing or the screen, you have to be efficient with what you do. This often means using the elements of art and the principles of design (standard stuff in any program of art study) in a utilitarian way. I try to use the same formalism when making art. The difference is that my main goal is to have fun while ending up with something interesting to look at.

Adam Rowe, "reversed metatronic solid (hexahedron)", polymethyl methacrylate, paint, the last breath of fresh air from 2019, 6" cube

RB: In Reversed Metatronic Solid (Hexahedron), you describe one of the materials as “The last breath of fresh air from 2019”. Can you talk about how/where you captured this breath and what you were thinking about?

AR: I’ll admit it; it may or may not contain the actual last breath of fresh air from 2019. It’s really just a reference to the subsequent year. Since it is a sealed container, it actually does have 2019 air in it, but I added it as a medium partly as an indirect dedication to a relative of mine who died shortly before that piece was on display.

RB: You’ve destroyed your own work over the years, burning pieces to make “cremains.” What’s this experience like for you? Do you feel emotional at all? Did anything about this process surprise you?

AR: So far, I’ve only really done it twice, but I do plan on doing it again in the future. I don’t think I would have burned any art if I had been hesitant. It’s a good experience: it’s definitely a way to let go of something. Sometimes when you make a piece, nothing ever happens with it and it’s just physically taking up room. If you’re in the same space with it every day for a long time, it can become baggage, a reminder of something that didn’t work out. It may not make sense for everyone to try, but for me it’s been a good way to move forward.

Adam Rowe, "Proof that I was Where I Said I was at the Time I was There", wood, paper, paint, cremains of 1999 senior show, 19” ø approx.

Adam Rowe, "hexahedron sliced by a surface-tiling curve (И 2)", steel, paint, 2 pieces, 10.5” cube when assembled

RB: What are you working on now and what’s next?

So far this year, my brain has been pretty consumed with another math / art concept I’m calling surface-tiling curves. It has to do with using segments made up of space-filling curves to tile the faces of regular polyhedra while maintaining unicursality. Just like with individual space-filling curves, as you iterate toward infinity, each surface approaches a fractal dimension of two. Thinking about things like transcending dimensions and never-ending functions are mentally paralyzing until you represent them with art.

If it sounds like I’m trying to sound over-technical, I apologize. My goal is just to make something that’s visually interesting and to have fun doing it. I’ve made several pieces using this concept, and there’s a lot more I haven’t even explored. I will probably be working on material from this idea for a while.

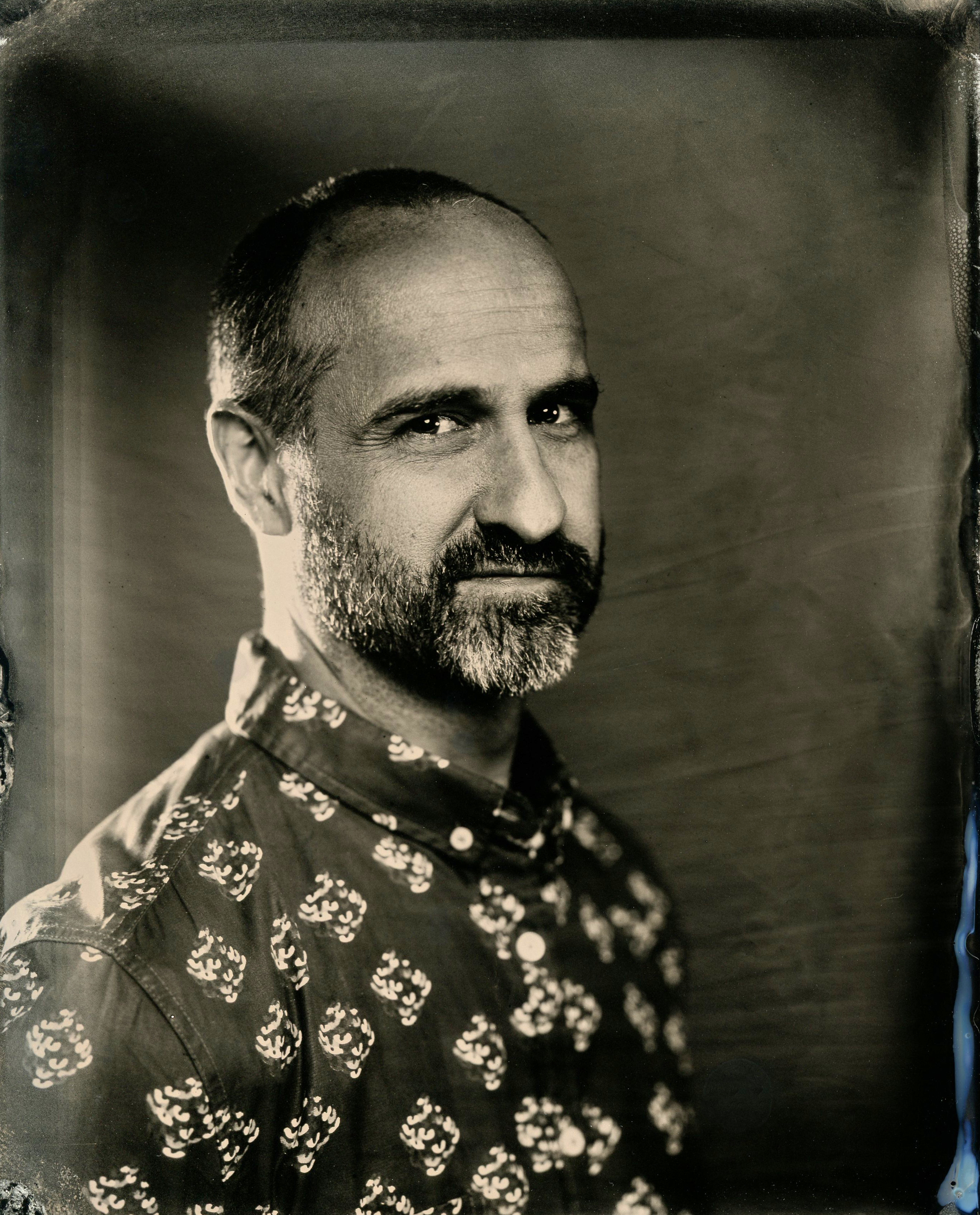

Adam Rowe (tintype by Kelsey Dillow)

Adam Rowe is a Knoxville native with a background in design for print and screen. He enjoys looking at art in terms of visual problem solving, with a fine arts approach to graphic design.

Rachel Bubis is a Nashville-based independent arts writer, regular contributor to The Focus blog, and LocateArts.org Web + Print Manager for Tri-Star Arts.

* images courtesy of the artist