INTERVIEW: JONATHAN ADAMS

NOV. 23, 2020

INTERVIEW: JONATHAN ADAMS

NOV. 23, 2020

Rachel Bubis: How are you? How has your quarantine experience been? Have you been making new work? If so, has your perspective changed or have you reflected on your practice in a new way?

Jonathan Adams: I would say fine. However, that seems to be a shared feeling with the general populace and peoples close to me. Quarantining before I have moved was ok. When I was working in New Jersey away from family, I tended to work on the logistics side of making art (research, e-mails, budget). However, when NJ seemed a bit too dystopian I decided to move back home. I’ve been staying with my partner and spending time with my grandmother; in short I’m definitely doing better!

A steady studio practice is crucial, but I was reminded that there are aspects outside the studio that aren’t about creation. Family, research in text, writings and lived experiences feed into the next images. I’ve been wanting my images to work towards being all encompassing, critique structures, acknowledge histories (shared and my own), be aesthetically pleasing and be enjoyable for me to make. I still believe in drawing and its ability to change what it represents; today is the perfect time to do such.

The works are not as large anymore but intimate and jammed packed. My homecoming to the South reminds me of the years after undergraduate working establishing a studio practice, but now I feel sharper and confident in my abilities to be able to continue my practice in this social climate.

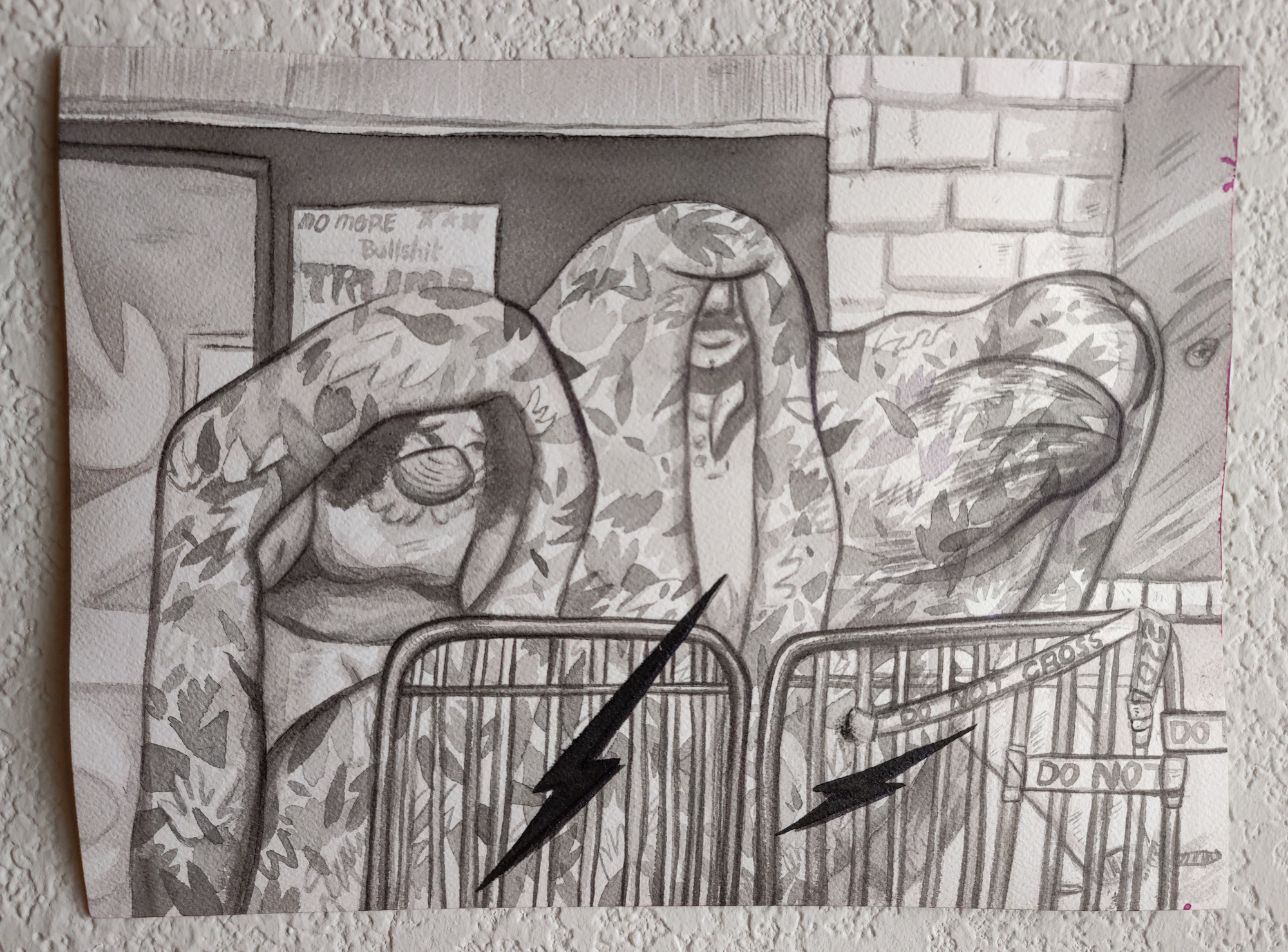

Jonathan Adams, "Midnight Hera/ Un-f@%!ing-touchable" (2020) 13" x 18", ink on paper, decorative paper

RB: You explain that each of your works begins as a piece of writing or a photograph that you have taken or found. Can you talk about the beginnings of I Want to Be Better, Please Show Me How (2020) and your process of translating it into the final image?

JA: For this image, I began to think about access and in-access. How does someone get into something exclusive, what does it take to be able to submit yourself to something and finally be counted amongst the other side? This thought process stems from my lower-class upbringing. A house fire left my family homeless in 2001. I thought about the disadvantages of my retired grandparents being denied from assistance because we lacked a home address. How many levels, what did it take to be finally counted as someone worth helping? Then how do you become economically advantaged? Is academia a way to becoming elite? Is this the right way?

The chase to something more or greater than ourselves is reflected into our culture and religion. I could practically feel the quiet roar of a southern choir. The giving yourself to an investment for something you consider to be warming. In my family archive, my distant relatives were being baptized. They were giving themselves to something in hopes of things being better much later.

I wonder what they say about their lives today. What if what we give ourselves to is hostile? Eventually I compiled these questions and other research into how I think about baptisms altogether. Finally funneling the imagery into a mechanic for my personal mythos; I hated making this drawing and almost threw it away hahaha. In the end, I love what grew from this work's creation. It’s so tacitly beautiful in person and it has informed so much of my practice today.

RB: A common theme in your work is smoke or dotted lines coming out of people’s eyes such as in Intimate Me (2019). What are you thinking about when you include this imagery?

JA: Knowledge. Burn out. Diversion. Cosmic. Antenna. Scarred. Horror.

RB: You describe your images of storms such as in Cataclysm 2 (2019) as capturing a “pure representation of trauma or conflict.” Has making these works helped you process the trauma and conflict you’ve experienced in your life?

JA: Of course. I place the stories, ideas, histories and things that I can’t resolve or represent yet into the gestures. Then it translates into staging somewhere for other stories. I like to think the drawings intimidate as much as attract the viewer. The storms are my way of exercising what I can’t put to words.

Jonathan Adams, “…and then there were three.” (2020) 8" x 12.5", ink on paper

RB: You worked on Kara Walker Presents, an exhibition of works by Rutgers MFA students and alums who “embarked on an investigative journey with her around themes of Memory, Memorials, and Monuments (MMM).” What was this experience like? Can you talk about your role in the project?

JA: Kara is as much an enigma as she is brilliant, this was before her debut of Fons Americanus at the Tate and during the first bout of monument removals. Iraq’s Victory Arch staged our questions like: “Who or what is deserving of a monument?”, “Does the community want this monument, who made it?", "Where did the money come from?”. The Arch was centered in a text alongside other readings as we ventured on our own, seeking monuments and unearthing narratives around them.

In a bullpen, boardroom, Daily Planet style “Whacha’ got?”, we presented our findings to the class. Each monument or lack thereof folded over into the work for the culminated show. I was looking into Paul Robeson’s political centering at Rutgers and greater New Jersey. I asked myself many of the proposed questions and then began to look to the public. I was looking for community engagement with the monument I was looking to create.

Paul Robeson singer, actor, all-star football player, activist, skull and cap society member; Black man. Son of a former slave, Robeson was disliked and wasn’t treated well during his attendance at Rutgers; 1915 was a different time. 105 years later he stands as the ideal student and renaissance man. I believe in academia correcting itself, but his presentation by Rutgers seemed like a garnering of reputation. Taking from a brilliant legacy by displaying his name and face everywhere.

Our original works were to exist as public works, however our exhibition format and design changed dramatically to what existed at the Army Terminal. The initial work was a collection of bricks laid into a triangular gravestone, each gilded in 24K gold and sealed to prevent water damaged. Displaying atop would be a relief portrait in soapstone with a proper eulogy; the bricks were to exist as take-aways. I was hoping passersby greed would take over and the monument would become a performance. The gravestone was his legacy. Eventually I disbanded the project in favor of the Cataclysm series, that was birthed from the Raritan River that reminded me of a good ole’ southern storm.

One of my favorite takeaways was the conversation around what a monument does. Monuments are unanimously chosen history that relieves us from remembering the history; the monument remembers for us. It’s a bit abrupt to place here but I couldn’t resist including this!

RB: In your Cistern performance piece in Brooklyn, you investigated spaces and power in the “exchange of truth withheld,” by inviting people to walk up to you and whisper secrets. Were you surprised by what people told you? Can you share the most memorable secret someone said to you? (I totally understand if not because it’s a secret haha).

JA: I can’t give away secrets, I’d violate my half of the contract. I was particularly moved by one that night that brought me to weeping. What I didn’t count on was the emotional freedom of the participants or the interactions. I believe the performance gives them a small chance to be seen. I would love to do it again, but it looks like distancing will be in effect for a while, it seems so oddly distant somehow.

Jonathan Adams, "sigh, lost" (2020) 8" x 12.5", ink on paper

RB: What are you working on now and what’s next?

JA: A book. Studio visits, peers and mentors have all mentioned over the years that I should make one and somehow it seems like just the right time to create one. About navigation, shifting iconography and nomadism. My current string of drawings helps reinforce that idea; Almost like a handbook. But then also I’m working on pretty much everything. So many drawings. I’ve been in academia for so long, it’s nice to be outside of it for a while.

Understanding my family dynamic, figuring how to work as a professional artist without the backing of an institution. On the other hand, I would love to lecture again. My students always kept my on my toes no matter how much I would prepare. I miss that dynamic and exchange of ideas. So… in summation, I’m living, eating noodles, napping, occasionally panicking, making art and looking to start a new chapter in my life.

"I was born and raised a Black/Latino man in the primarily white Christian south of Bristol VA/TN. I felt culturally isolated and that the narrative that was given to me was not my own. Lacking a personal cultural narrative led to difficulties finding a community and understanding my bi-racial identity. Within this fraught environment, visual art became a bridge of understanding for initiating dialogues and introspection. As a result, my work blends mythologized observations of the Appalachian region of America, personal narrative and the shifting socio-political landscape to explore the limits of identity and the human condition.

I am continually inspired by contemporary and past artists. After working with Kara Walker, I better understand the implications of having one’s subjectivity relate to the work and the skill of relieving one’s artwork of having to carry all the answers to every conversation. I feel akin to Michael Armitage’s representations of oppositions, as his depictions of multiple vantage points highlight the totality of the region's discourse. Finally, Honoré Daumier is someone I cannot ignore. Daumier’s scathing caricatures and deft hand helps me understand how a drawing can control a narrative and create social change.

Each work begins as a piece of writing or a photograph that I have taken or found. The process of translating the research materials into a visual language becomes a meditation on the subject and removal of bias; As I work, I only seek to compare, empathize and understand these observations. Upon completion, I refer to the finished entry and even compare it to other works.

This diaristic approach allows me to shed light on and create a discourse around veiled narratives such as humanization of black diaspora and facets of power structures in the historic South. Furthermore, by engaging the language of graphic novels, each piece is an aspect of a larger narrative furthering the story in different ways by their juxtaposition to other works. I wholeheartedly believe that imagery is passed down as information and becomes an agent of change through creation and dissemination. That by creating the work, I can further my horizons of understanding, push for emotional vulnerability and hope to inform viewers of these struggles."

— Jonathan Adams, 2020

Rachel Bubis is a Nashville-based independent arts writer, regular contributor to The Focus blog, and LocateArts.org Web + Print Manager for Tri-Star Arts.

* all images courtesy of the artist