INTERVIEW: JERED SPRECHER

JAN. 20, 2026

INTERVIEW: JERED SPRECHER

JAN. 20, 2026

Jered Sprecher, Looking for the Eye, 2022, oil on canvas, 72 x 80 inches, photo by Bruce Cole, courtesy the artist and Ferrara Showman Gallery

Anna Mages: In a statement from your show at Tri-Star’s Candoro Marble Building, you discuss your work as exploring the “precarious relationship between nature and technology.” The way that you describe this relationship recalls the theme of “nature v. nurture.” Do you see these relationships as part of the same conversation?

Jered Sprecher: Those are definitely related to that. When we talk about nature versus nurture, it [refers to] a lot of developmental things. Were you born that way, part of your nature? Or was it how you were nurtured, how you were brought up, how culture has affected you? In some ways, I think that definitely feeds into my work.

I often think of both nature and technology as types of wilderness. There is a certain wilderness, a sort of wild unknown, or frontier in terms of technology. In just the last couple of decades, people are talking a lot about AI, how the internet has changed life so drastically, and how we use smartphones. And then with nature, we are used to the wilderness and the unknown, whether it is the immensity of the ocean, standing on the edge of the Grand Canyon, or being lost in the woods. There are these wildernesses and unknown places that confront us. For me, I think there is a certain immensity of nature and also technological sublime pushing in on our own humanity. So, I think that the idea of nature and technology is connected to nature and nurture. How we are born and how we are nurtured by the world affects and forms who we are.

AM: As you explore this relationship with technology, you mention that your work reflects a relationship between what is outside and what is being reflected upon glass or a screen. Do you find that technology has a utilitarian role for your work?

JS: There is basic technology that I use, such as my cell phone. If I see something that has resonance to me, I make note of it by snapping a photo with my phone. If I need to, I will edit my photos in Photoshop to blow up the image, crop it, play with the color, or even edit something out. There is that type of utility, [but also] the utility of daily life in which we use the technology that is around us. Whether it's hopping in the car, listening to a podcast, or emailing someone, there is technology that can make life easier. But, there are also ways that it can complicate our lives. I can spend too much time reading all the headlines and scrolling, which can bring me to a halt of focusing on the daily tasks ahead of me. There are larger existential questions concerning what it means for me to use and rely on these tools. And how do they change me? How would I be shaped if I was not using them?

Jered Sprecher, Three Stems, 2024, watercolor on paper in handmade frame, 22.5 x 17 inches, photo by Bruce Cole, courtesy the artist and Steven Zevitas Gallery

AM: Do you use photos in abstracting your still lives and landscapes?

JS: I like to joke that I learned Photoshop in 1997 – the time when if you asked it to do too much, a ticking time bomb occurred and it would crash. When I am painting, I think a little in terms of a rudimentary Photoshop as I consider the transformations that I can make and the ways that an image can fall apart.

I am also thinking about different types of perception. Sometimes I paint from direct observation, looking at whatever is in front of me. Often there is a matter of translation that is happening – whether it be basing a painting off of an image that I have torn out of a magazine or a photo that I took. If it is a photograph that somebody else has taken in a magazine, it has been printed and sitting around for years before I have tried to paint it. I take photos of landscapes or flowers reflected in a window, which disrupts the image. Maybe we see some of what is reflected or some of what is on the other side of the window.

There are so many different ways that we can use the world around us and understand how to interact with it. If I am going to paint something from direct observation, different things happen than if I work from a digital image. It is almost like there is different DNA embedded in the paintings that arrive from these different approaches. It is similar to a recording artist choosing different microphones or studio settings, each giving the music a different feel.

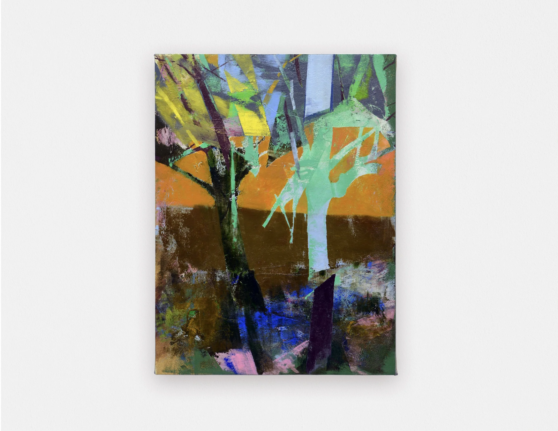

Jered Sprecher, Stone, 2021, oil on canvas, 24 x 20 inches, photo by Bruce Cole, courtesy the artist and Whitespace Gallery

Jered Sprecher, Rite, 2024, oil on linen, 72 x 60 inches, photo by Bruce Cole, courtesy the artist and Steven Zevitas Gallery

AM: Describe the role that colors play in your work. A piece like Stone obviously functions more monochromatically.

JS: Sometimes when I am thinking about the direction of a painting, I list a couple of things that I want the piece to feel like. And so, when I was finding an image that would ultimately become the painting that is Stone, there were several things I was thinking about. I knew that I wanted to make a grayscale painting that felt like a low relief carving, similar to something you would find on a gravestone. I also wanted it to feel like a tintype photograph in which the color was mostly emptied out of it. I held these ideas or “feels” with me as I was working on the painting and letting the color develop. The large floral blossom in Stone is the main actor, then the composition becomes a little less focused around the edges of the canvas.

Rite has a lot more color and a more active composition. In some ways, it feels as if these flowers are up in the air or chaotically arranged. There are bits of blue and red, and other colors buried in the painting that are peeking through. I wanted this painting to have less of the somber energy in Stone, but [instead] have a more chaotic feel to it. Rather than being formally composed, I wanted it to feel more like things are being discovered amidst the movement going on.

AM: Do you have a source that you are pulling these ideas from, or is it more a matter of play and invention?

JS: There is a sense of play and invention, but oftentimes it is also holding paradoxical ideas. Since Stone feels like a stone carving or a tintype photograph, I wanted the emotions and what the material felt like to carry over to the viewer. A painting like Rite with a dynamic composition feels like we are caught in the midst of motion and frozen there. There is still a sort of latent sense of movement that is possible. It is not zoomed out or some formal arrangement, but it feels like your nose is pressed into the bouquet of flowers. In some ways, it presses in on the viewer [who feels the experience] of having flowers against your face.

AM: The color of Stone is interesting in terms of the feeling associated with it in comparison to the typical associations of flowers.

JS: I love how flowers have so much symbolism and metaphors attached to them. They are these beautiful things and painting them never captures that beauty in full. You are setting yourself up to not quite meet the goal. There is a long discourse about how flowers are connected to the intertwined relationship of life and death. I have made paintings of thistles, which are historically thought of as depicting sorrow. Roses have a truckload of possible meanings. Dahlias, irises, tulips - they all have different historical weights that they pull with them as well.

AM: Right, they have a connotation as a whole body, but then individually, there is a whole other language there.

JS: Yes, that is a good way to think about it in terms of connotations.

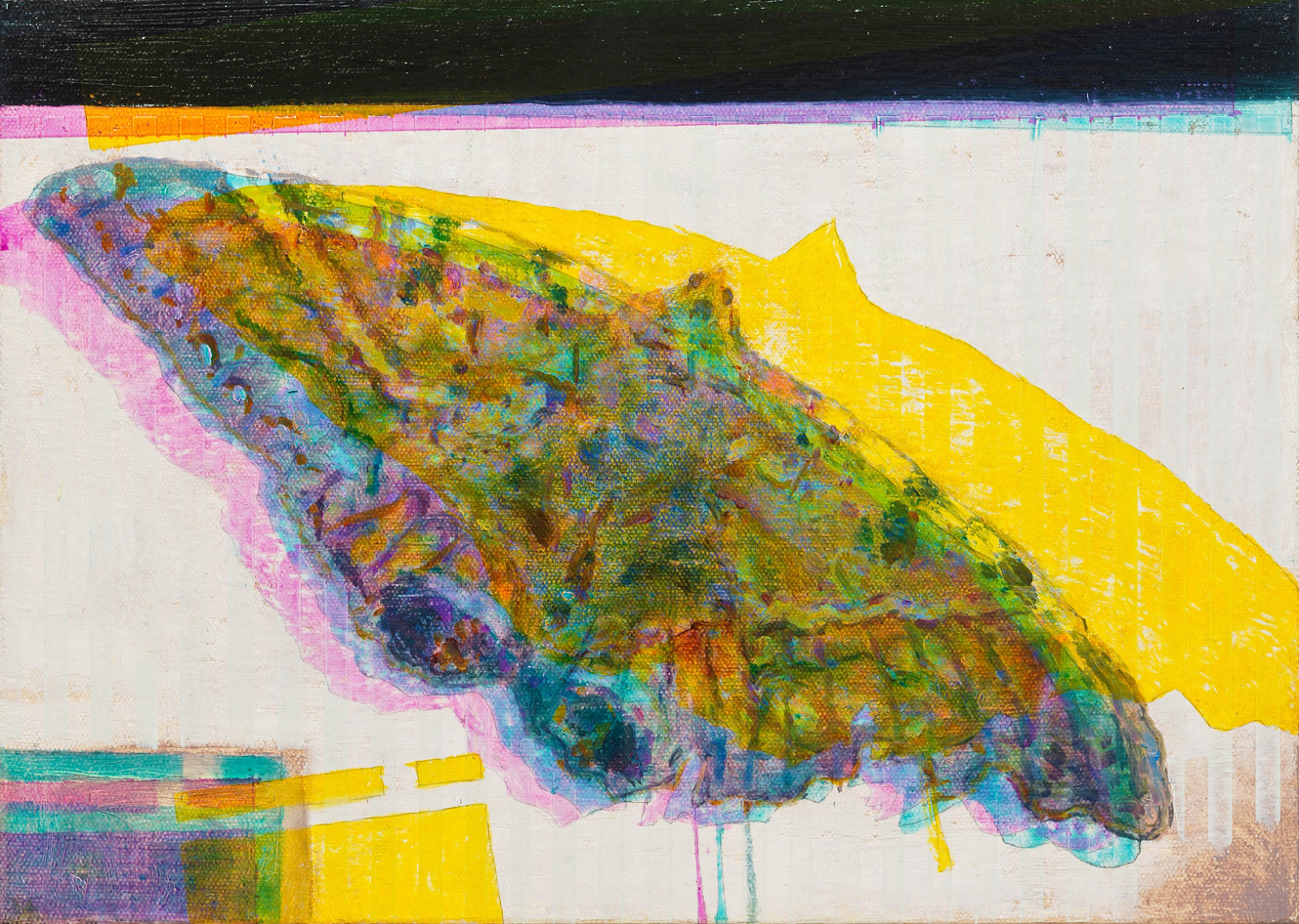

Jered Sprecher, Omen, 2021, oil on canvas, 10 x 14 inches, photo by Bruce Cole, courtesy the artist and Ferrara Showman Gallery

AM: Turning to your piece Omen, it looks almost as if a printer had an error or ran out of ink. I am curious to hear the process behind this piece.

JS: In that particular image, it does have an element that recalls when an inkjet printer messed up. It is another example of where I want the image to feel like a certain list of things. It might be that I want the image to feel like a 3D image viewed without glasses, or a misregistered image from a failing printer. There is an element of failure, unexpected outcome, or a sense that we are not seeing the full picture.

This particular image is a life size painting of a black witch moth which I encountered during a summer that I lived in Marfa, Texas as an artist in residence. One morning I woke up, went into the bathroom, and saw this moth that was nine to ten inches across in wingspan. I was not expecting to find this huge moth so I snapped some photos of it, not knowing what I was going to do with them. I did some research and found out that black witch moths migrate through that area of Texas, between the United States and Mexico. I also learned that it is an omen of bad luck - thankfully, I am still around with nothing bad to attribute to the moth.

The same way that flowers have the possibility of metaphor or symbolism, I like the way that this moth appeared out of thin air and intruded into my life. Nature was poking its head into what I thought was a squared off, protected space.

I have made several paintings that use this similar motif of the silhouette of the moth with offset, misaligned coloration to them. The pieces are in some ways an outlier to my recent work since it is more animal than plant or flora. But, prior to my flower paintings, I had done quite a few paintings of the bird species black-legged kittiwakes. These images were similarly based on photos from my childhood that I revisited later in life.

AM: I enjoy how you talk about intrusion of space. Insects are weird in the sense that most people are afraid of them and see them as a horrible intrusion.

JS: I have three boys and they each have different reactions to insects. They want to get up close to see what it looks like and how it is put together. They have the wonder that is there when you look at nature. We do not always have to understand things, but if we have this kind of wonder, we can spend time with it, observe it, and get to know it a little bit better.

The other day I started thinking about how when I come to my studio, there is often a different insect near the door that I notice. I was just appreciating the fact that it is not the same type of insect, but new ones that I will find from time to time. It is easy to pass those things by and dismiss them, but they are all interesting things that we run into as we are moving throughout our day.

Jered Sprecher, Array, 2024, oil on paper mounted on 32 linen panels, 76 x 124 inches, photo by Bruce Cole, courtesy the artist and Ferrara Showman Gallery

AM: How did you work on the panels in Array? Did you think about them individually or as a unified piece? Do they require each other?

JS: I have these 16 x 12 in. sheets of paper that I keep in my studio which I often clean my brushes on or put extra paint on. I had accumulated several of these used pieces of paper before I had this idea that I would tape them all together on the back and hang them on my studio wall. I projected the image of some dahlia blooms onto it. As I was working on it, there was a checkerboard or gridded pattern, as if it was tile work. I would paint areas, but also let some of that pentimenti, the layered brush strokes from all the cleaning of my brushes, come through.

There is a blue that you see coming from the top portion of the painting which is where I started to cover up some of the dahlias to add more sky. In the original images, there are some reflections which I kept pushing and pulling. Sometimes it was just a mass of paint and other times you could see different parts of the flowers emerging.

When I finished the painting, I took it off the wall and separated the pieces of paper by a couple of inches. Pulling the grid apart allowed each one to become its own individual painting. But, they also needed to work together as a whole.

I have not displayed it like this, but when I was documenting the piece, I shuffled the individual panels around so that the image was not recognizable. Ultimately, I displayed it so that you can see the flowers themselves, but it was still distorted because of the separations between each segment of the painting.

AM: I wish I could look at each one individually. They seem like they could function independently, even just as small formal and color studies.

JS: Yes, I wanted each individual panel to ultimately be an interesting image, a little remnant of the larger whole.

Within my work over the last 20 years, I have explored what happens when you put an image under stress and begin to pull it apart. If you lose some information, how does that image become transformed?

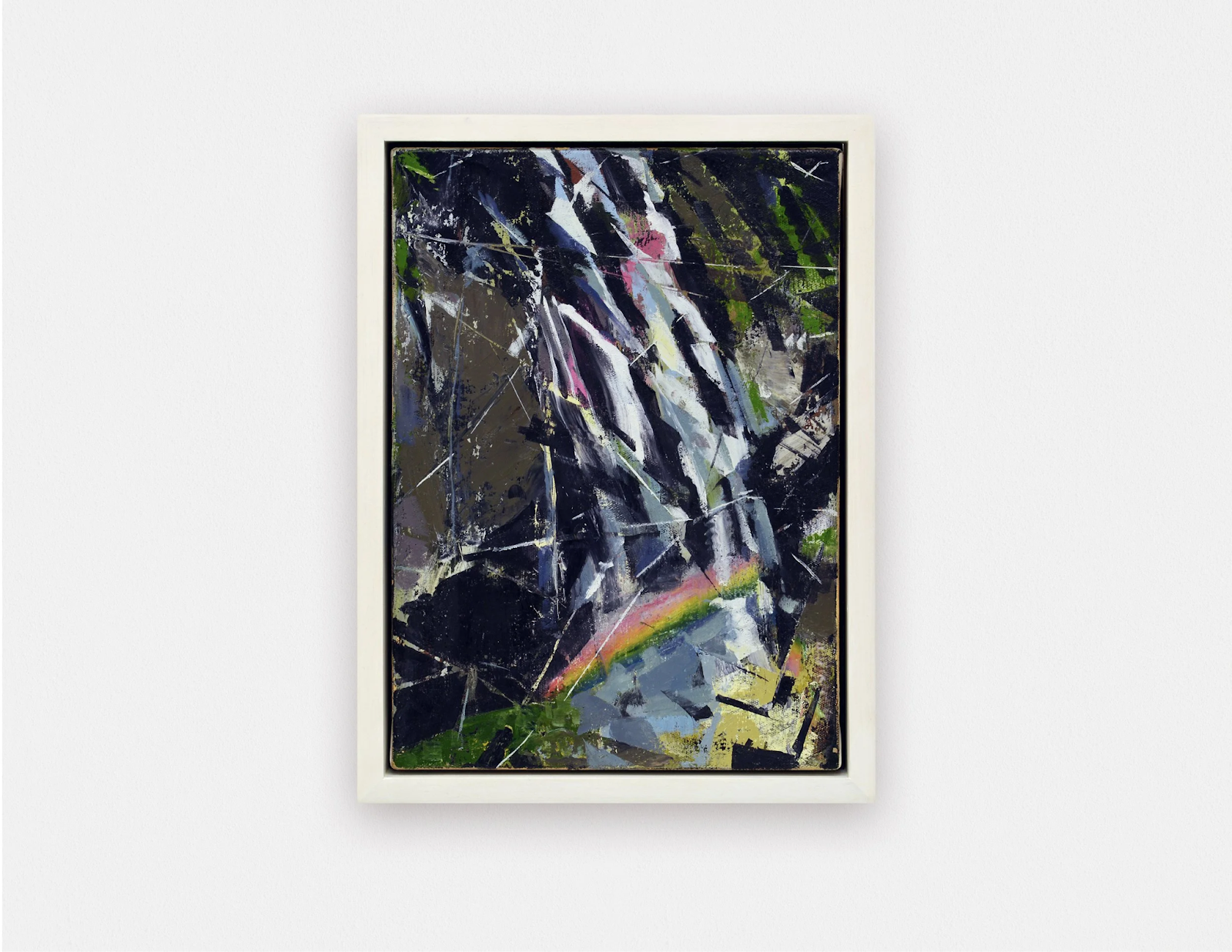

Jered Sprecher, The Fall, 2024, oil on canvas in handmade frame, 10 x 14 inches, photo by Bruce Cole, courtesy the artist and Steven Zevitas Gallery

AM: In terms of your process, do you find a subject matter then place it behind glass to paint it? Or, do you just happen upon your subjects?

JS: It tends to be more finding it. I was just visiting a house that a friend is working on restoring, but there is a lot of property from the previous owner that is still in the house. There are these wreaths that were hung on different doors behind glass and windows. I was taking photos of these old, ragged wreaths with plastic flowers, but the glass was also reflecting the trees in the yard behind me. They look promising as potential subject matter to interrogate. For me as an artist, I do not know if they will come to something, but I am excited about playing with them and trying to see if I can pull a painting out of them.

In “The Fall,” I had a magazine image of a waterfall that had been in my studio for years just because I loved the image. We all love certain things – sunsets, waterfalls, etc. I always thought this one image of a waterfall would be an interesting subject for a painting, but I was not quite sure how to deal with it. Then, one day, I needed to clean my studio so I crumpled it up and threw it in the garbage. The next day, I thought that maybe I should not throw that away. So, I pulled it out of the garbage, uncrumpled it, and hung it back on my studio wall. Since I had crumpled it, there were some areas of the black in the photograph that shone brighter because they were reflecting the light in the studio. This gave me an answer of how I could possibly paint that image of a waterfall. I moved forward with this fractured photo to make “The Fall.”

AM: The title seems to give some direction and yet I do not really know what I am looking at. Am I falling into this? How do I approach it? What kind of sources are you drawing from art historically?

JS: There have been different moments in art history and artists who have been important for me. It was eye opening when I realized that a bunch of these French painters who we know about - Manet, Vuillard, Degas - were not painting apart from photography. We think of them as always painting from observation, but they are working near the advent of photography. All of those strong shadows that Manet uses come through because he is looking at photographs in which the subject is being heavily lit. We see images of Degas’ paintings where he has drawn an image over and over again. Then, when we see his archive, there is a photograph that he had worked with somebody to take and then he used that as source material. There is a Edouard Vuillard painting that I really love which has this really weird frame painted around its edge to it. You are wondering, what is this French decorative edge that he has put on this landscape painting? Then, you see the source of the photograph that he used and you realize that it is actually the curled edge of the photographic paper that he has just replicated on this larger scale painting.

For me, those bits of artifacts that come through in the DNA of an image ultimately are really important. Art historically, I love the grids and compositions of Piet Mondrian. It is quite lovely to look back and see his steps from making paintings of flowers, trees, landscapes, and windmills towards more simplified forms.

Somebody like Mark Rothko who reorganizes how we think about space is really important to me as well.

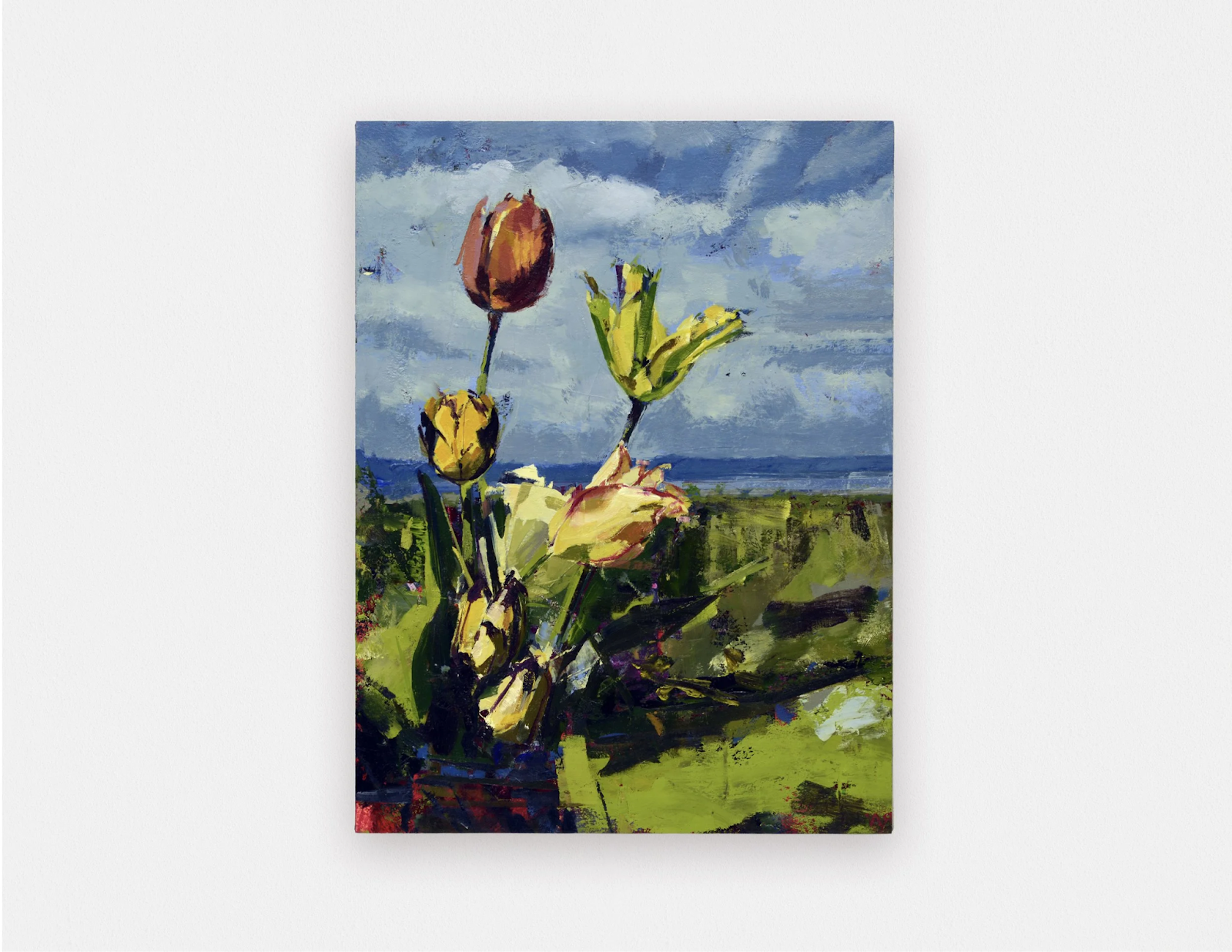

Jered Sprecher, Horizon, 2024, oil on paper mounted on linen and wood panel, 16 x 12 inches, photo by Bruce Cole, courtesy the artist and Steven Zevitas Gallery

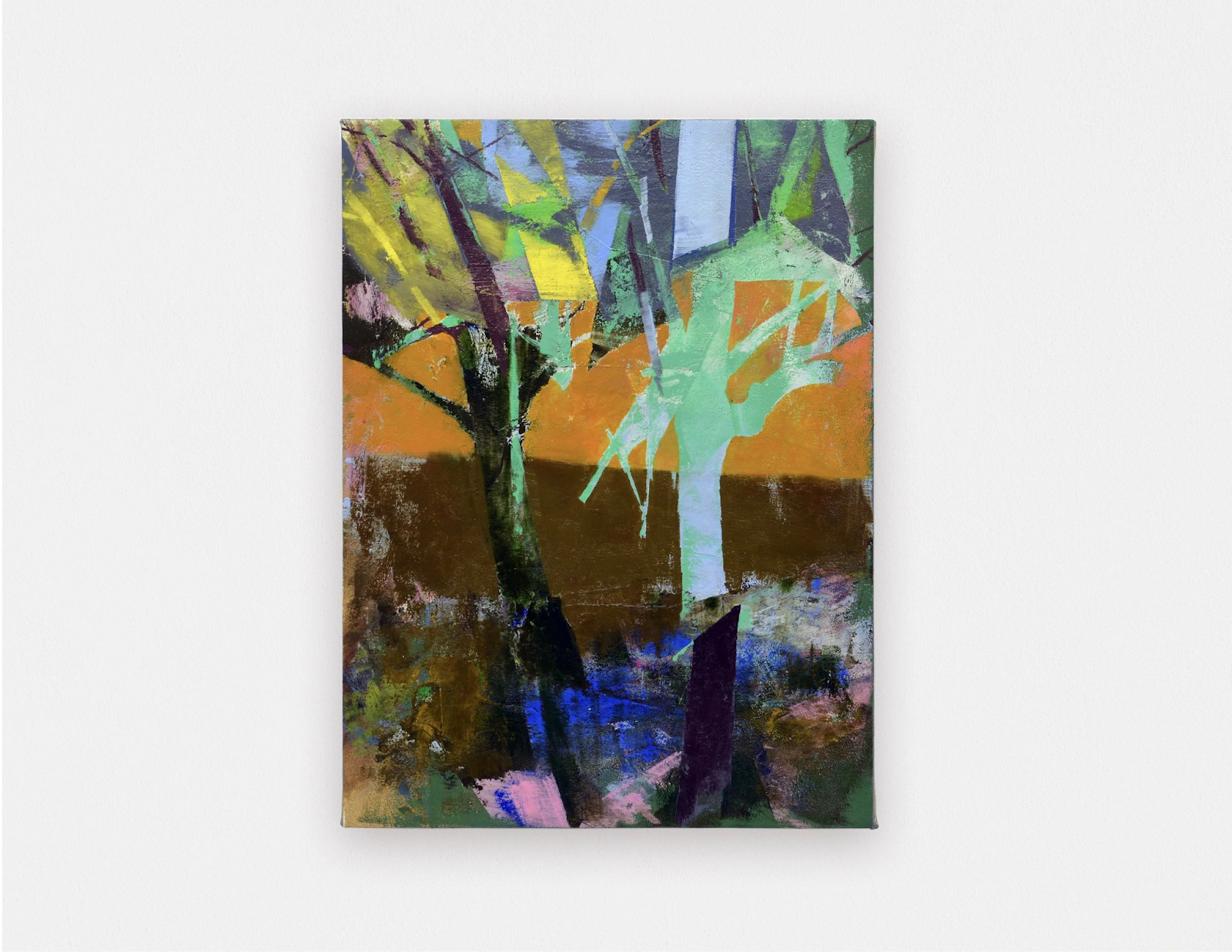

Jered Sprecher, Prayers We Did Not Pray, 2024, oil on paper mounted on linen and wood panel, 16 x 12 inches, photo by Bruce Cole, courtesy the artist and Steven Zevitas Gallery

AM: Tell me about Horizon and Prayers We Did Not Pray.

JS: Horizon is a little bit of an outlier for me. It comes from a pretty bucolic image that I found from an old gardening book. Most of the images in the book are black and white, but this came from the one full page in color. Something struck me about - it has these tulips as the main characters which are really pushed toward the viewer. Bisecting the picture plan is that horizon line. There is a blue, gray sky above and then the hazy, out of focus, green landscape that is just beyond the flowers. In some ways, it hit the ideals that we think of in terms of landscape. There is a lit bit of ocean on the horizon, there is blue sky, and then there is all this green. And yet, there is this flower as the main character in the foreground almost like it is a portrait.

I thought there was something in it that plays into our ideas of what we think is beautiful. I painted this to get it out of my system which is often how I work. The image haunted me. At this point, I think I have made five or six of these paintings. There is one in my studio right now. Each one is a little different - sometimes the sky is more gray, sometimes it is a brighter blue. It changes over time, but it is this constant thing that I can check in with and test my own temperature with it. It is a weird type of beautiful, but also a bit haunting.

Prayers We Did Not Pray is another example of using sheets of paper that I clean my brushes off on. I was looking at the mess of paint and starting to see things in them, like when someone stares at clouds and notices different forms. I also wanted to start painting some trees from memory. As I was painting on them, sometimes I would lose the form of the tree as it got cut off or disjointed. Sometimes I would paint around the tree or let some of the visual noise and detritus shine through. I feel like they are a bit apocalyptic. My family usually drives to visit relatives in the Midwest about twice a year. While I am driving, I always find myself looking at the different types of tree. Sometimes it is a dead tree or an aggressively trimmed tree, all of which take on different forms. What is this sort of sculptural tale that they tell? Do they even become a stand in for humans?

AM: What role does your background in history play into your work?

JS: I have taken a number of history courses, first as a high school student, then in college and graduate school. I still continue to read lots of history, philosophy, religion, really anything I can get my hands on. I try to encourage my students to read widely. History is really important. It is easy for a person to think that their ideas are new, but there is a humility that history offers in terms of being in conversation with other people [from the past]. There is also a sense of a larger river that we wade into and the historical precedents that are there. There is a dialogue that we hold in common with other human beings through time. I think that is quite beautiful. While you do see the myriad of missteps through time, you can also see the great and beautiful things that people have done. For me, there is a certain foolishness in not knowing history and the perspective it offers into the present.

Jered Sprecher is an artist who makes paintings, drawings, and installations that abstract the landscape to explore the precarious relationship between nature and technology. His work wrestles with the beauty and complexity of the environment and how we as humans interact with the world around us both directly and mediated through technology. He received his BA from Concordia University and his MFA from The University of Iowa. Sprecher has exhibited at The Drawing Center, Brooklyn Academy of Music, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Des Moines Art Center, Hunter Museum, Asheville Art Museum, and Espai d'art Contemporani de Castelló. He has had solo exhibitions at Jeff Bailey Gallery, New York; Gallery 16, San Francisco; Steven Zevitas Gallery, Boston; Kinkead Contemporary, Los Angeles; Whitespace, Atlanta; Ferrara Showman, New Orleans; and the Knoxville Museum of Art. He is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Bailey Opportunity Grant, and a Tennessee Arts Commission Individual Artist Fellowship. Sprecher has been awarded residencies at the Marie Walsh Sharpe Foundation, the Chinati Foundation, The American Academy in Rome, and the Irish Museum of Modern Art. He is a Professor at the School of Art at the University of Tennessee. He lives and works in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Anna Mages is an Intern for Tri-Star Arts, currently based in the Chattanooga area.

* images courtesy of the artist, Ferrara Showman Gallery, Steven Zevitas Gallery, and Whitespace Gallery