INTERVIEW: HEATH MONTGOMERY

JAN. 23, 2025

INTERVIEW: HEATH MONTGOMERY

JAN. 23, 2025

Wesley Roden: You employ methods ranging from 3D printing to attaching a pen to a power drill. By using tools which streamline or automate artistic processes, or even work against it, do you question the role of effort or craft in artmaking?

Heath Montgomery: I do question the roles that are prescribed for artmaking, but my view is that artists have always used what they have access to, or used what they have to make new tools.

I like the experiential nature of the internet and video because it can be profoundly impactful, but there is nothing physical to be bought. Most of my work early on was about being an object. That has shifted now and I prioritize the experience. I think art is inherently linked to “play.”

There needs to be rules, but the creator gets to make the rules up for the game they’re playing. All artists have to choose which part of their process is automated. I mean, there may be some painters that make their own paint or make their own brushes or paint on non-traditional surfaces but that's all part of what makes it Art. Be deliberate about which tools you are exploring in your practice.

Heath Montgomery, Laocoon Series - The Truth and Other Malicious Gifts, 2022, acrylic and graphite on panel, PLA filament, LEDs, mirrors, plywood, and microcontroller

WR: Does your interest in a particular subject, for example, pyrite, originate first from attention to its formal or symbolic qualities? How does your initial perception of the subject shift as you explore through art-making?

HM: I was drawn initially to the shape of the pyrite and the fact that they grow in cubic structures that are sometimes nearly perfect. It's interesting to me that rocks can grow at all. It makes me think of “time,” how relative it is, and how it passes differently for different organisms on the planet.

But pyrite also has symbolic qualities. Being “fool’s gold” is something that's interesting to me because it implies it's foolish to find Value in such a thing. It shares some valuable qualities and is actually quite useful as a semiconductor material in solar panels. It was even used long ago as an early explosive material. It does not have value as currency though, which I think is a good metaphor, or Paradox, in our current culture where value is learned, but also adapts over time. Something that did not have value in a particular time is incredibly useful or valuable in another time. Truth changes too.

Heath Montgomery, MEMEmory, 2021, acrylic on panel

WR: Given the interactive nature of many of your works, how do you adjust art to match either the audience or the environment? In what ways does the gallery lend itself to the work, and in what ways do you hope to expand beyond that setting?

HM: More now than in the past, I think about where the art is and not just what it is. I think about how people in that space are going to see it and experience it. Some of my work has been projected on gallery walls, and I like that a lot. I'd like to explore projection mapping and altering the space of the gallery as an event or experience that only exists for the duration of the show. I also have been exploring Public Works that can be found outside of the white gallery walls... I feel like galleries or museums are more performative and people are much more aware of the context that they're participating in whereas if they see a sculpture somewhere unexpected, they may be more open to it.

WR: You mention an interest in questioning value. By reframing art historical imagery, such as Greco-Roman sculpture, how do you question how art has traditionally assigned value?

HM: I think art is basically people processing or working through their current culture and the ideas and systems they're faced with. My work tends to be playful. I like to play with ideas, especially teetering on what people take seriously. I like to make fun of it, but more like laughing with absurdity as opposed to at it or as a reaction of Despair. I think it's more like, “This is our lives and this is how crazy it is!” But using history allows you to tell a story, or at least combine what it is that I'm doing with a story that's known. That's a common denominator, but it's a cultural common denominator. That stuff's changing pretty quickly now because of the internet and connectivity of people digitally.

WR: How do you play with the value attributed to recognizable images as opposed to patterns? By depicting legible images amidst abstraction, what connection do you form between the two? How does this line of investigation continue into your use of grids or computer generated patterns?

HM: Images that are recognizable are patterns; they're just cultural patterns. The only way we learn things is through repetition. Seeing a thing in your culture and a different context gives it meaning as it relates to the other things that you see, hear, or feel when you're experiencing it. I like to think my work is a question about these things and how they relate. You know, I don't really have an answer, and I don't know that anybody else does, because the questions are evolving just like we do... That is pretty esoteric but, “answers” are an abstract ideal more than an absolute fact. Like place holders or a saved game.

Yeah, I think that I'm trying to at least illustrate that things are related. But it is on-going and that's how we process culture; by relating our current experience to other things. Also, with abstraction I've always felt there are these different ideas about what it means. For example, you know math seems really concrete because it's known, true and absolute. 2 + 2 is pretty much always going to be four, but the concepts themselves change... Numbers are base 10 because we have 10 digits on our hands and every language says the numbers slightly differently but all have a common concept... If we had more digits on our hands we'd have a different number system. And what those things are called are based on idiosyncratic noises that people in a group decided was the name or sound that one makes when they're conveying a message about that concept. So yeah, patterns and recognition try to get in there with the language of what we see and how we talk about what we're used to, while also messing around with the meaning.

Heath Montgomery, Memento Mori - Flowers, 2022, acrylic on panel

WR: By presenting paint splotches and tape lines alongside detailed renderings, how do you question both notions of intent and the work being “finished” as indications of value?

HM: This is a good question about ideas of “finished.” I mean, I also think “finished" is an abstract ideal... When you're dead you're finished, I guess, but you're still kind of around in the minds of other people, so you're not “finished.” It's kind of a conundrum, and I like making comparisons, or having things side by side that are distinct seemingly. Maybe you're kind of forcing or allowing someone to experience them as equal expressions of the same completeness. Maybe a pattern that seems unfinished is just a language we don't yet speak or something like that. But I think we could still appreciate the sounds, and maybe it conveys some meaning, like when we hear a person speaking in a language we don't understand and there's other Clues, like their face or the tone of their voice, that may imply meaning.

Yeah, I think we wrap up a lot of value in understanding or knowing, and I'm not certain I agree with that. I think feeling is a good way of understanding, but also, talking about those abstract ideals, knowing and understanding are these things we agree on, that are maybe important values to Aspire to but are all contingent on continuing to ask better questions that relate more specifically to whatever it is you're trying to understand... And with that in mind, I guess I'm asking people to ask why these two things are together and think about how they might relate... There's not really a right answer. There's just a question.

Heath Montgomery, Studies - Symmetry Painting, acrylic on panel

WR: Can you elaborate on the process for creating one of your collage and acrylic works. Do you begin or end with collage, source collage for inspiration, or collage your own paintings?

HM: Sometimes I have an idea that I want to start with or I'll see something like a cast of a Greco-Roman head, some pattern somewhere, maybe a photo of buildings cropped awkwardly with no Horizon, or just little splotches that make me think of the world as this really complex place. So I'll start painting sometimes, with just a surface where I'm playing around with paint, gluing things down, or cutting things out in a particular shape. Then I just start arranging them either as I grab them or as I look for a particular thing, color, shape, or pattern, and I get more deliberate as I go on really. It's just me kind of exploring what I can see and how things look together, but I deliberate about what things I'm putting together. Not everything's a choice on my part, and sometimes I get surprised.

Heath Montgomery, Collaboration for Mixed Metaphors w/ Rylen Thompson - Lunar Groove, 2022, acrylic, collage on panel, 18 x 22 inches

WR: I laughed seeing one of your paintings consisting of a machine dripping paint through holes in the wall. Is it ever your aim to emphasize process, especially in artforms like painting, which often prioritize the final product?

HM: I'm so glad to hear that. A lot of times I laugh when I'm making my work. I think smiling and being happy about what you're doing is essential. A lot of my work is actively seeking catharsis or some type of release or flow, whatever you want to call it. But yeah, I like seeing the way stuff looks, and some stuff's pretty funny.

I mean Roxy Paine does these big glob paints/sculptures, and of course, Pollock did drip paintings. It's kind of silly but it's also kind of beautiful. I think Pollock's work kind of looks like the solar system, or what you might imagine inside of an atom looks like. It is fun to think about those two things that are incredibly distinct in scale... but yeah if you can't laugh at something, there's enough stuff you look at that makes you sad. Maybe my art specifically is about trying to find Joy or laughter in the Wonder and complexity of the world. My process has developed since I was in middle school and college, taking different classes, having teachers give you some assignments, and then seeing how many of the rules you can break while still doing the project. I guess I'm still living in that context. As a teacher, I'm constantly thinking of ways that I can constrain so that students can practice using a particular tool but also explore their capabilities and not hinder their creative use and expression.

Heath Montgomery, Pour Paintings - Leftovers

WR: In work which is either machine driven or consisting of natural processes, do you question the authorship of the artist? Especially with work which monitors the audience, do you ever rebrand your role to documentarian?

HM: I have never thought of myself as a documentarian. I'm still creating the system. It was my idea to implement it based on circumstances; where it is, where the gallery is, or who interacts with it. But I don't really question authorship so much...

It's kind of cliche, but I think you know nobody exists in a void, so everything's a collaboration in my mind. Even our thoughts are somebody else's thoughts regurgitated, reprocessed, or collaged with other thoughts, and then we give you the cliff notes of our version. I'm just trying to figure that out, but I do like to use the word natural.

Anything we make is part of nature. The internet, I think, is nature. It's just a really sophisticated and expensive ant hill... So I think authorship is overrated. It's a way for people to make money and own an idea. That just seems silly in a bad way. Silly, like absurd.

WR: Apart from your video and design work, you also show your life drawings. How important is representational drawing for the rest of your work? As both an educator and an artist, what do drawing basics mean to you?

HM: I’m conflicted about this. I do think it's important to show expertise and Tool use, and that's maybe what I’m proving to the naysayers. “All this guy makes video work! You must not be able to draw very well.” No, I have practice. It's just not as useful, or doesn't get at exactly what I'm trying to say as well as video, something that's adaptive, or an experience... A drawing shows a moment.

I've never been much of a narrative artist, though I declared my major in undergrad at RISD as illustration... I wanted to learn how to draw and paint really, really well, so that I could draw whatever I wanted, or do whatever I wanted. I think that's an important process for an artist... so that they learn skills and have those skills become credible tools to give them a kind of formal gravitas... but also just confidence. Confidence in exploring, mastering, and utilizing new tools.

WR: Your work crosses a multitude of media and disciplines. How often do ideas cross from one medium into another, and has being interdisciplinary allowed ideas originating in one medium to be more fully explored in another?

HM: Aw, thanks for asking this question! I get to use this term (maybe I made it up… maybe I heard it somewhere); materials or media agnostic.

I don't really think ideas should be bound to any one particular material. I think it's important for artists to explore what they want to explore, but also, I think, for my practice it's important to choose a material that best suits the message I'm trying to send, or the conversation I'm trying to have. A lot of this work is exploratory, so I'm just trying different things out. Different people are going to be drawn to different media for different reasons, but if the conversation I'm having with all these different media are in a similar vein, then hopefully different folks can converse about the topic, or at least engage in a more complex and enriching way. Maybe they just laugh, which I think is important too.

Heath Montgomery, Not Recording, 2022, raspberry pi, camera, wood, and plexiglass * This live video feed is playfully distorted to encourage interaction. This is contrasted by its potentially disingenuous title.

WR: Many of your drawings consist of graphs, tables, and notes. Considering the processed-driven nature of your work, are these drawings pivotal in the role they lend to that process? To what status do you elevate those drawings and at what extent do you distinguish the drawing from the product?

HM: As my series that I have been working on for a while evolves, I start to think everything's part of the same thing. So I do have a series, or a couple different projects that have distinct names, but the Fool's Gold concept is the through line currently. Everything is based on some process or some system, whether it's a drawing, painting, sculpture, digital assemblage, code, or whatever. It's always process, and, like I was saying about the materials, the materials change while the idea, concept, and really the kind of the questions that I'm asking and engaging with is sort of the same conversation. It's like, “Well... we got all these different things, and they seem really distinct. But are they actually getting at the same thing which is maybe some meaning or relationship?”

So I really like drawing (in undergrad) in general… One thing I really liked about it was when I had an art professor in grad school. His name was George Dimock. He taught at UNCG and wrote a lot about Contemporary Art... He was pivotal and enlightening to me through this idea of indexical marks. These are marks that are made not in reference to some image but are themselves a reference to the thing that made the mark. That's kind of a mouthful, but I was also introduced to (Installation artist) Robert Irwin in grad school, and his book Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing one Sees, which is also a mouthful. I was also a big fan of (Nashville native, Minimalist painter) Robert Ryman. I think we're just caught up in names and categorization... It's important and serves a specific end, but also, by having that specific end, you're blocking out these other ideas. So I'm, at the same time, trying to be hyper diligent about the system or the process, but also open and agnostic at the same time. Going back to the agnostic and that question. Agnostic basically just means you don't have an answer. You're not saying there's nothing out there or the things that are out there are meaningless. You're just saying, “I don't know what they are. Maybe they're too complex for me to understand,” but you still want to try and appreciate them in the way that you do... or the way that I do by, I guess, continuing to engage with it and not writing it off as something that you know… like the judge in Blood Meridian.

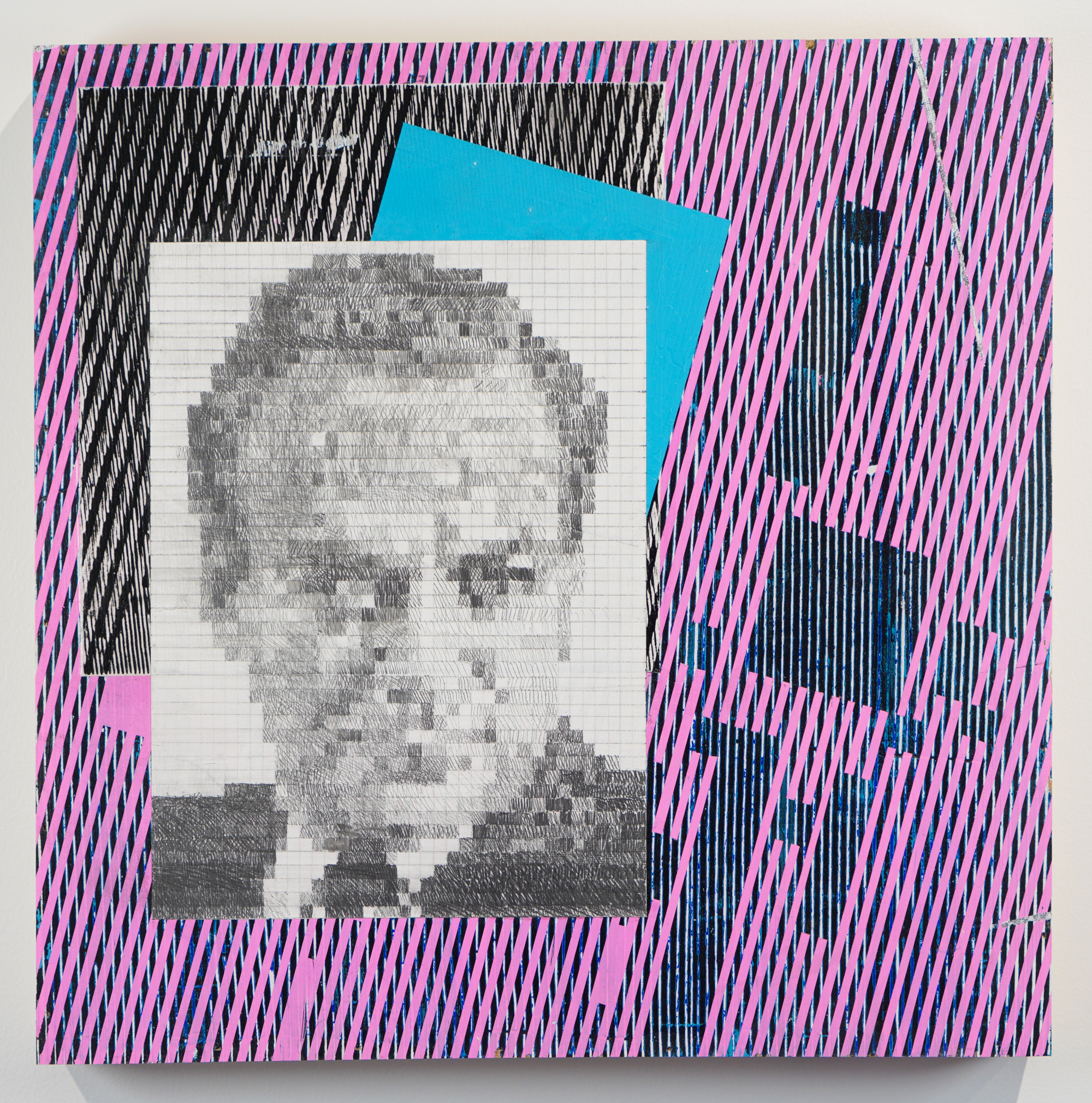

Heath Montgomery, Everything in Nature is Natural (Feynman Pixel Portrait), 2021, acrylic, gesso, graphite on wood

WR: Are you ever concerned about legibility in your work? In what ways do you challenge the viewer as opposed to inviting them in, and how does the work balance accessibility with misdirection?

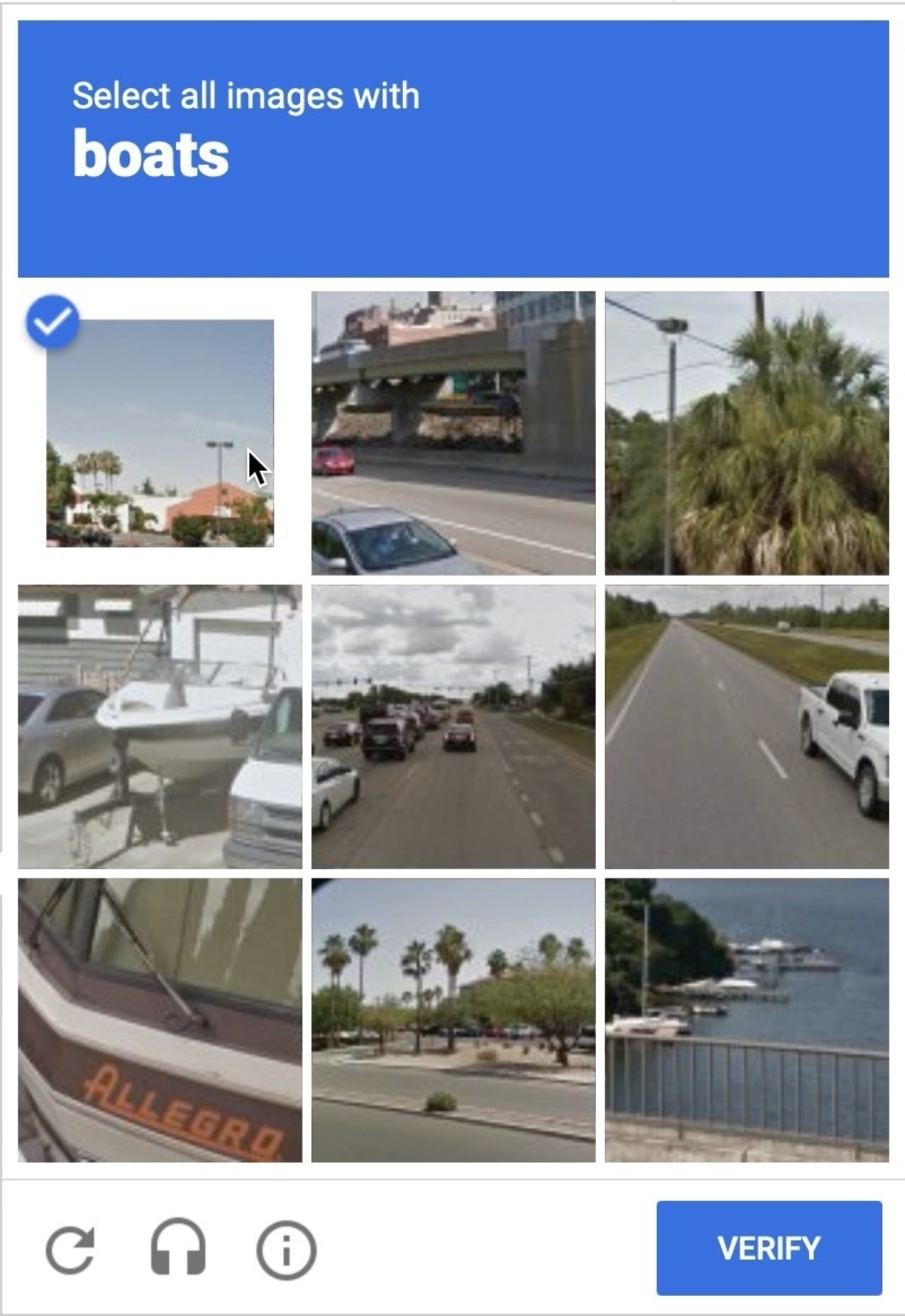

HM: Ha! This is a great question. I've started focusing a little less on the message that's being conveyed, having a particular thing that I want a person to understand didactically, or whatever, and more just kind of inviting a conversation... So with (the work) I'm Not a Robot, some people look at that and they're like, “Oh there's a person hacking this computer,” or, “this is weird.” They don't really know what to think of it, because it's just a video of me solving a bunch the recaptcha test and then at the end it just saying, “I’m not a robot,”... which is this little checkbox that you have to check and then this automated system that we've designed basically confirms your Humanity, which is kind of ironic to me.

Yeah, I got lots of questions about accessibility and misdirection. I think a lot of things pretend to be something important when they're not. They're just kind of a waste of time. It's become part of our culture; this time wasting.

Heath Montgomery, I am Not a Robot, 2022, video loop of robot quizzes

Heath Montgomery and his family live in Chattanooga, TN. He works as an artist and educator. Over the years, he has worked as an educator, interior designer, and for a technology company. His work spans many disciplines and draws on contemporary methods focusing on the experience and traditional means for creating impactful objects and experiences.

Wesley Roden is the Gallery Associate at Tri-Star Arts and received a BFA in Painting from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville in 2023. Based in Knoxville, he currently works in digital and mixed media in a continually evolving practice.

* images courtesy of the artist