INTERVIEW: MEGAN LEDBETTER

SEP. 05, 2024

INTERVIEW: MEGAN LEDBETTER

SEP. 05, 2024

Megan Ledbetter: First off, I would like to say thank you for your interest in my photographic practice at The Field, which is still in progress as I work towards a local exhibition at Stove Works in November 2024.

Rachel Bubis: You are very welcome! I'd like to begin by asking about this project, where you document an area in Chattanooga that has served as a municipal burial ground for the poor and dispossessed in operation from 1890-1912. Your large format black and white photos depict the current state of the location over a year of seasonal change. How did you first hear about and become interested in this place?

ML: I first learned about The Field sometime in 2022 from a local news report shared around on social media highlighting the discovery of an abandoned burial ground by historian Michael Hitt in Red Bank, TN. As a member of the Red Bank community, I was encouraged that our mayor, Hollie Berry and other elected leaders were committed to honoring that space, creating a citizen’s group to participate in the process. Red Bank partnered with Trust for Public Land starting an initiative to recognize and protect this location; that initial phase included research and narrative crafting done by Donivan Brown, the former chair of the Ed Johnson Project. As a local art professor, I’ve often taken my Introduction to Art classes to visit the Ed Johnson Memorial and rely on the resources by community leaders like Donivan and the Hunter Museum (I’m always thankful for Adera Causey) to navigate class discussions on the topic.

In early 2023, I initially contacted Donivan to see if there was a need to visualize The Field, to make a small portfolio of landscape photographs that document its current state of abandonment. Donivan put me in touch with Noel Durant, the Tennessee State Director of TPL, and the timing aligned with their intention to publish an initial report on the burial ground (published July 2023). I worked from March-June of 2023, making landscape pictures for TPL, but I kept going back as the space seemed to transform dramatically over the summer months; I became completely captivated with The Field. I spent time looking at the photographs more deeply, compiling a notebook of historical newsclippings, and writing a grant offered through the Current Art Fund. Upon being awarded in October 2023, the momentum of the project dramatically moved forward; the grant became the lifeline for the breadth of the past year's work.

RB: What's your experience like going there - do you have to get permission? Do you have to wear a lot of bug spray?

ML: This feels like THE big question of the moment as the word is spreading about The Field; how, when, and who should have access to the burial ground in its present state is a difficult question to answer. Technically, anyone can walk into the location, as it is public property (owned by the City of Red Bank), adjacent to the White Oak Connector Trail which leads to the Stringer’s Ridge trail system, and there are certain rights for burial descendants. (There is a need for a robust historical deep dive to identify any living descendants.) But this is no ordinary cemetery as it has certain vulnerabilities and can be dangerous for the casual visitor; there are also discussions about potential vandalism and treasure hunting on the premises. So often I find myself torn between remaining transparent about what I see and experience at The Field and feeling resolved to protect what exists there. Specifically, the photographs of the burial markers represent an aspect of vulnerability as they make it quite clear that they simply lay on the surface of the ground.

Back to the question of access… The partnership between the City of Red Bank and TPL through Resolution No. 24-1678 created a “community of stakeholders” to shape the process of repair, which includes safe access, both now and in the future. It’s encouraging to know that not any one specific person is making decisions about how things move forward. (I’ve linked below the TN Historic Cemetery Preservation Program webpage, which does explain some of the state guidelines for cemeteries in lay terms.)

At this point it is difficult to know how much time I’ve spent out there, by myself. (I do prefer to go alone) I photograph often during seasonal transition, like after the cold snap last October or when it snowed in January. In fact that day in January was one of the most memorable visits to The Field, not because it was 7 degrees Fahrenheit and the snow was a glistening crusty surface, not even because I heard Sandhill Cranes migrating overhead, or found the most beautiful light to photograph burial marker no. 2. It was because the atmosphere of the place had changed, something different happens to the air at that temperature and when you experience those sensations some residue of that might get recorded in a photograph. There is also a picture of the retention pond from February 14th, I’ve never seen the surface of the water like that, kind of glowing green with shafts of white light cutting across, there was a submerged tree root or branch with finger-like appendages pointing to the surface. That’s a very satisfying thing to witness as both a real world experience but also seen later as a photographic image.

And by the way, the bugs aren’t as bad as the brambles, although during the hot summer months the chiggers are terrible, so bug spray it is.

RB: Your work was selected for the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. In an interview with them, you talk about how your photographic tendencies shift during different periods. Has your approach changed in this body of work, and if so, how? What are you searching for as you capture the mood/tell the story of this place?

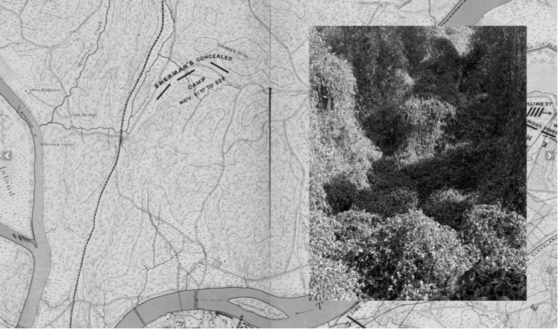

ML: The Field is more than a burial ground with complex and overlapping histories at the site, from Sherman’s Concealed Camps in 1863 before the Battle of Chattanooga to the Hamilton County Municipal Burial Ground from 1890-1912 to the Pine Breeze Tuberculosis Sanitarium from 1913-1968 and then finally Pine Breeze Center from 1968-1982. There was also a moonshine still busted by local police in the late 1920s, not to mention author and illustrator Emma Bell Miles wrote her final work Our Southern Birds published in 1919 during her stay at Pine Breeze while dying of tuberculosis. Finding and sourcing information about the place has informed the way I make the photographs or even later connecting a picture with something I’ve read or seen. For example, the topo maps and photographs visually relate to one another or historical newsclippings that are descriptive of the visual experience.

Working at The Field over the last year or so has been quiet and solo, a huge shift from making pictures of people which requires a different type of focus, a different type of dialogue. Most of the dialogue while making pictures there is internal, inside my own head, yet still in commune with the place; getting to know The Field is not unlike building a new friendship over time. I believe at this point we are well acquainted.

RB: How does the medium of black and white photography lend itself to this project?

ML: I have worked with black and white film for over 20 years, and the view camera for nearly that long. Over that time my eye has been trained to translate the chromatic value range of a scene to an achromatic value range; that part of the “seeing” is now an intuitive part of my working process. Additionally, there is a built-in layer of abstraction when you translate a real world scenario into a black and white image; one way it works for photographing at The Field is to “tame” all the endless waves of green, especially in the summer. Going into this project I was keenly aware that black and white imagery is often considered moodier than color work as well as being associated with Southern Gothic themes (do yourself a favor and go watch Night of the Hunter from 1955). My intention is to lead viewers through a visual narrative that contains a range of emotive expression, from low-key to high-key imagery, from somber to even celebratory at times. The Field is endlessly elusive, compulsive, shifting so the act of discovery feels indefinite and expansive.

I will also mention that the view camera, a quite basic piece of camera equipment, allows for endless possibilities of image making. When I say basic, I mean that the camera itself isn't that different from the original designs of the mid 19th century: there is a lens, extendable bellows, and a ground glass for seeing the image (upside down and backwards). This type of camera allows for endless adaptability as the lens and film no longer have to be parallel, which can adjust the plane of focus or perspective, offering viewers a kind of “super-sight” through the rendering of an image. Photographing with a small aperture also changes spatial relationships, creating images where near and far become confused, compressed. Looking at the ground has become important for the narrative sequence as well, an approach born from the necessity of knowing exactly where I’m stepping, standing, or placing the legs of the tripod, as the kudzu obscures what’s beneath, but also referencing the unseen realm just below the surface.

RB: What has been the response to your work so far? Have you had any pushback?

ML: What has been fantastic about this process is that the majority of the “responses” I get to the work are real-life, face-to-face interactions and dialogue about the endeavor. I had a virtual studio visit with a dear friend, Fabiola Menchelli, who asked me all the hard questions that I knew she would, mostly about my intentions and the deeper content of the work. Reading some literature on the topic can direct those conversations, books like Grave History: death, race, and gender in Southern Cemeteries, edited by Kami Fletcher or Cemetery Citizens, Reclaiming the past and working for justice in American burial grounds by Adam Rosenblatt.

RB: I know this project is still in progress, but do you have any thoughts/hopes about the possibilities for the future of this location? What would you like to see happen here?

ML: It’s been a privilege to listen: to the landscape, to community members, to those who are tasked with making decisions. The changes there aren’t up to me, of course, but I feel committed to remaining open to the process of repair, and willing to share my thoughts, research, and photographic narrative with stakeholders and citizens alike.

In many ways the work I’m doing now, hopefully, is holding a space for descendants and future visitors, adding to the historical narrative through telling the story of now.

I’ve sat in that space wondering how the place will change with forthcoming interventions… how do you maintain that feeling of wildness, Stringer’s Ridge is a wildlife corridor, while finding ways to honor the dead that lie beneath? How does research, design, and intervention work together to create an accessible and meaningful space for future visitors? These are the big questions that become baked into the narrative quality of the pictures. Questions I can’t actually answer; I’m just along for the ride.

RB: You’ve described making work as “a great responsibility.” Can you talk more about this and how it affects your practice?

ML: Not everyone conceives of photography in this way, but for me representing a person, place, or thing does feel like a great responsibility. I see lens-based work, like photography, as a practice where the person making the picture brings with them their biases, life experiences, personality, intention, technical skills, etc. Essentially photography is a subjective medium, which makes it a wonderfully adaptive and compelling practice, but also as something to be aware of when walking into a marginalized space. I’m very open to learning more, arming myself with knowledge, and not shying away from the difficult questions this process has led me through.

RB: Besides this body of work, what are you working on and what’s next?

ML: My plate feels full, in the best way possible. Between my personal practice, which involves interacting often with my community, historical research, photographing (which involves processing and printing), teaching at Chattanooga State (I usually teach 3-4 courses per semester), there is my family life (I have two young daughters and a partner), as well as my volunteer work with the Red Bank Public Art Board.

This summer I have focused on portraits of those who are associated in some way with The Field, and maybe I’ll find a place for the photographs I made of Michael Hitt when we visited together last February.

Michael Hitt, February 2024

Megan Ledbetter is an artist and educator based in Red Bank, Tennessee, whose lens-based work explores personal, cultural, and historical narratives tied to place.

Her current photographic project, The Field, is part of a larger collaborative initiative to recognize and repair a derelict municipal cemetery for the poor and dispossessed in operation from 1890-1912, discovered recently in her hometown. Through generous support from the Current Art Fund (2023-2024), her work combines visual imagery, historical research, and community engagement to shine a light on the complex overlapping histories at this abandoned burial ground.

She earned her MFA from Massachusetts College of Art and Design (2011), a BFA from East Tennessee State University (2008), and a BA from Auburn University (2002). She attended Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in 2013 and was awarded a Resident Artist Fellowship from Anderson Ranch Arts Center in 2014.

Rachel Bubis is a Nashville-based independent arts writer, regular contributor to The Focus blog, and LocateArts.org Web Manager for Tri-Star Arts.

* images courtesy of the artist