INTERVIEW: JOE LETITIA

FEB. 13, 2024

INTERVIEW: JOE LETITIA

FEB. 13, 2024

Rachel Bubis: You describe your work as resonating around the notion of faith, its tangibility, and the “intricacy and length of a soul’s pondering.” This is reflected through your process of layering and abstracting imagery of subjects such as church buildings. Can you talk more about this? Has this process informed your own spirituality and faith?

Joe Letitia: The process started from teaching students a project where they produced an abstracted mandala type image based on their names. They would trace the design of their name over and over in a mirrored repetition. This process always left behind residual impressions on the white scrap paper I would have the students put under their work as they traced on top of them. I found them beautiful – complete and incomplete – residue of the making and the made. They were like impressions of a thought coming toward you and moving away simultaneously. I collected them because I could not throw them away.

I began to start making works employing this notion of process. The first paintings I made were based on Caravaggio’s painting The Incredulity of Saint Thomas. The only image I used to make the paintings was the finger being pressed into Christ’s wound. Caravaggio’s painting is such a solid example surrounding the notion of belief or faith. I feel for the first real moment in the history of painting, the artist put himself in the painting - himself and others like him. In that sense, the work was of its time. I don’t like to use the word sin, maybe transgression and admission of our nature, identity and perception of ourselves. This is something I had been thinking about since my plywood paintings. I think of the layering of the single image as a way of encapsulating within the frame of a canvas or paper the sensibility of an infinite gesture. Like looking through or into a box, or door, or window of wishes and regrets back to my birth and toward my last day. Each time the image or mark is laid down, it's a personal gesture of this sentiment. I regard the church paintings differently, in that they maybe symbolize the structures that contain all those hopes and regrets - I guess you could call them prayers and confessions. If the Doubting Thomas paintings generate and tally an example of my individual ponderance, each church represents a dwelling that generates and contains these thoughts as well as those of a congregation. The overlapping outlines of the structures make them transparent, as if a wall could ever separate one from God. But a great deal of my art from the moment I left high school to go to art school has in some regard scrutinized both my existential understandings and questions about God.

RB: Some works are made by the repeated replication of a core image. For example, your most recent paintings that incorporate outlines of simple and severe early American churches. Are these specific churches? Are they local? Do you start with a photograph or from memory?

JL: The churches are all regional, South Knoxville, Cades Cove, Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina, etc. I photograph them and then make a simple outline drawing from them. I grew up in the Catholic faith and left the church for almost 10 years. When I moved to Knoxville to be with my wife, I worked in carpentry, taught adjunct at UT - basically flying by the seat of my pants. We were married in a one room church on the eastward bend of Wears Valley Road (Headrick's Chapel). After buying a house in South Knoxville, I came across a 100 year-old rural Methodist church (New Salem UMC), which seemed to call to me with its architecture, its intricacy - yet limits on decoration, and its groans.

My family dropped in one Sunday and during the service, the pastor gave a call for some repairs that were needed. I showed up the next morning with my tools, but was the only one there beside the pastor. We became great friends (his name was Steve Tuck). After spending a cold morning on my back in the damp crawl space under the bell tower, Steve headed me in the direction of a twin sister Methodist church of the same age that needed more extensive mending, and after spending three months working on this church (Beulah UMC), my affinity, curiosity and lore for such buildings grew.

Joe Letitia, Shaped Notes Only, 2024, gouache and pencil on canvas, 36” x 36”

RB: Can you talk more about your inspiration behind the plywood/ wood grain body of work and where those core images came from?

JL: I like to refer to the plywood paintings as one plywood paining that was always in the process of being made. As I worked on those pieces, whether it was an 8’ x 8’ or 1’ x 1’ surface, the brushes used were the same size, and the entire surface received the same amount of attention, touch, and inflection. After grad school when I first moved to Brooklyn, I was working with the process of painting, sculpture, and printmaking, and never felt a strong enough desire to identify my expression with any particular process. Whatever manner I worked in however, was not helping me pay my living expenses. Consequently, it was being a carpenter, where I learned the process of every part of the job from demolition to finished work. As a carpenter, I was able to scrutinize the essence of process, labor, and the meaning of a two-dimensional idea that transforms itself into an articulate and interactive space. Almost every aspect of the process contains as much de-constructive information as constructive. The outcome of the project would reveal itself, and also acquire stability through layers. The plywood used to sheath the structure is, in its essence, a modular object and surface made out of layers. Each layer of veneer is a slice out of a tree’s circumference. An individual veneer has an ingrained and strong tenancy to curl up on itself. However, a sheet of plywood gets its stability from the laminating of these layers back to back, and side to side, so that the natural insistence and opposing tendencies in each layer, is engaged in a constant tug of war. The character of plywood’s structural compliance takes advantage of the boundless and vagrant impulse in nature.

The things that make up our identity, whether they are inspirations or aggravations, lie within us like sedimentary layers of earth. One covers the other and, when exposed, reveal conditions of the individual. It was the idea of this kind of stratification or veneering of truth, and the manner in which one might alter their self-image that I found interesting. This is not always apparent to others who behold them, for where there appears to be stability and sincerity, there may often be insecurity and undoing.

The fundamental resolve of the plywood paintings was to question the integrity of representation and identity in what we take for granted as truth, especially with the increasing technology that envelopes our culture. I wanted to present this concept from an extremely pared down and essential vantage point; where the extreme gesture of the materials was at hand, and where this gesture is not diluted through embellishment, arrangement, or composition. I did not want to combine painting and sculpture in a way that would call attention to some form of sympathetic merger or choreograph an intermingling dynamic between the mediums. I simply wanted to layer the truth of one thing over the truth of another, and examine how the identity that is apparent in both objects becomes unstable and disappears into each other.

In the sculptural sense of a thing, plywood maintains the dull thud of a banal and isolated object, but is engendered with the potential to fulfill an abstract complex conclusion. The same can be said for paint, except the range of implications between paint as object and paint as complex conclusion are rife with historical predilection.

“I wanted to get the paint out of the can and onto the canvas… I tried to keep the paint as good as it was in the can.” - Frank Stella

The paint loses the apparentness of paint because it so closely resembles the object it covers, and the plywood loses the apparentness of itself in that its visible surface is not entirely its own. The thing is at a loss for itself.

Joe Letitia, Kaaterskill Falls after Thomas Cole, panels 1 and 2, elevation 3D sketch, 1995, oil on laminated birch plywood, 16” x 18” x 8” (derived from topographic map of area Thomas Cole painted – top panel are the elevation lines in between those in the bottom panel)

RB: How do you decide when a piece is done, when the process of abstraction is at a place you’re happy with?

JL: Finishing a work is intuitive. But as I mentioned in my thoughts on the plywood paintings, it often feels as though the work is never finished, but rather left behind visual residual of what I am thinking about…. but it does take me a long time because I have to maintain the detail and minutiae regardless of scale.

RB: Do you follow the same process every time or does it vary?

JL: There is a core aspect of the process that remains the same from piece to piece, even going back to my plywood paintings. There is a mantra-like repetition, a quiet and insisting chant that embraces and directs the labor of it…. a path to follow.

In the plywood paintings, I once likened the process to a Richard Long walk where the grain of wood is a path. And I would attend to the entire surface of the plywood, following the path of the grain as it exists. It exists in nature and is represented in the veneer of the plywood as a slice of time in the order of nature. The brushes are the boots used to follow the grain from on edge to the other and back again.

“My work is visible and invisible. It can be an object (to possess) or an idea carried out and equally shared by anyone who knows about it… a walk is just one more layer, a mark, laid upon the thousands of other layers of human and geographic history.” - Richard Long

In my church paintings, and more particularly evident in the drawings, there is a linear aspect that becomes forefront in the process. As the conglomerations and layers of church outlines merge and overlap, some fade out of view and others may become more apparent. At some point in the process, I will go into the drawing and find a line entering the edge on one side and make it more prominent connecting to any line that might intersect with it from segment to segment. This will continue, meander, and zigzag up down side to side until it eventually reaches the opposite side from where it started. I repeat this and create many paths as well as false paths. I think this stems from my interest in Islamic arabesque and medieval manuscripts like the Lindisfarne Gospels.

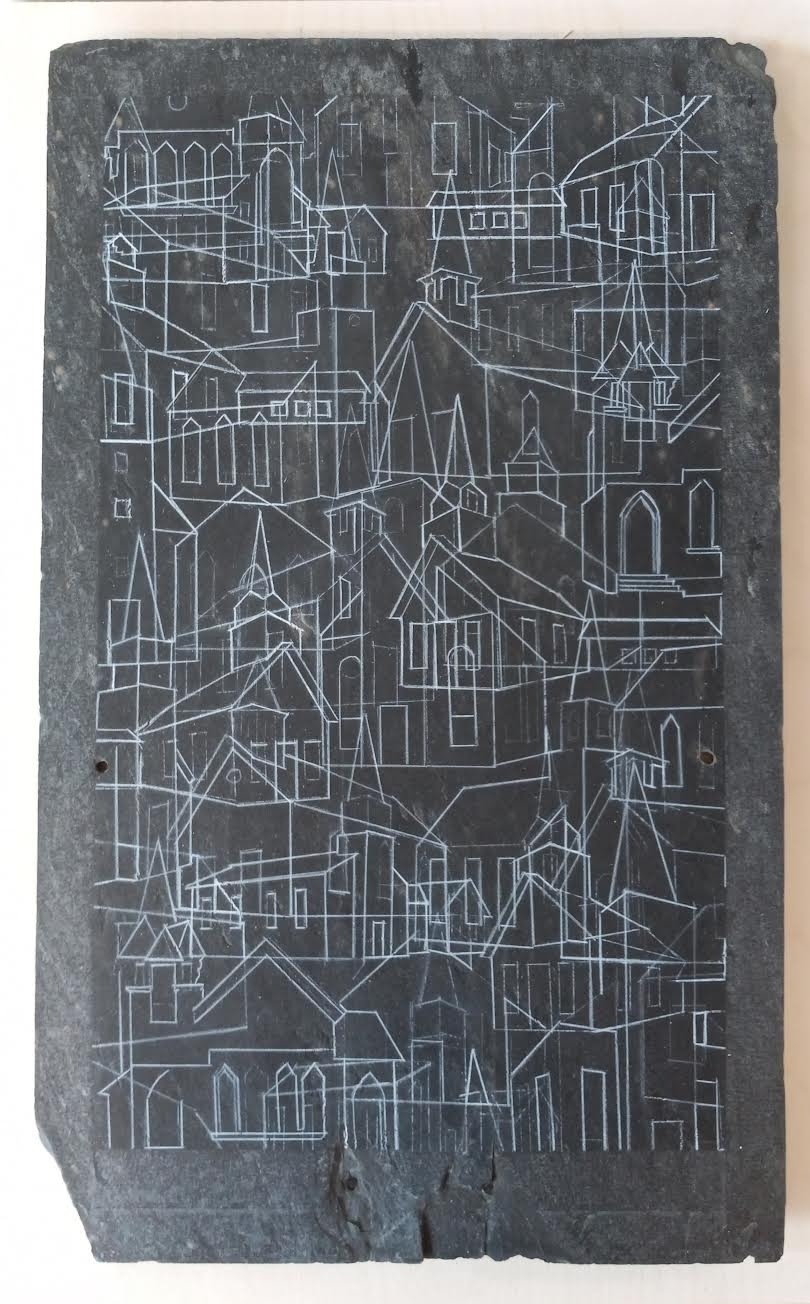

Joe Letitia, Chalkboard Lesson 6, 2023, pastel and prismacolor pencil on slate roofing tile, 12” x 20”

RB: You worked as an assistant to artist Chuck Close as well as the sculptor/ photographer, Sandy Skogland. What was the most surprising thing you learned from working with these artists? And/ or what did you take away most?

JL: Working for Chuck Close was an incredible experience and opportunity. In the time period that I worked for him (1991 – 1996) he was incredibly empathetic, inclusive, thoughtful, funny and helpful person to work for. His intelligence and personality made you feel like he wasn’t bound to his wheelchair or that he had a very intensive disability. But if anyone knew how much he struggled with it, I certainly did. From the first day of working with him, I had to be inserted into his family and it was profoundly sad to be in his home looking at all the family photos on the walls of him carrying or wrestling with his kids or gardening and walking down the beach with his wife Leslie. When I say he was inclusive and thoughtful, he would never make me feel like someone he paid to get him from place to place and set up his paints. He would always introduce me as a painter and make me feel like I was a part of what he was accomplishing. When he offered to visit my studio, this was no easy task for him physically. I lived in a partially abandoned five-story warehouse building in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. I had to get him out of his wheelchair, and help support him to walk up the steps into the entrance, before he could even get on board the rickety freight elevator to get up to the 5th floor. Chuck even took the time to visit the other six artists who had spaces in my building. Once when I brought him out to his summer home and studio in Bridgehampton, Long Island, he took me to the cemetery where Ad Reinhardt and Jackson Pollack were buried so I could take rubbings of their headstones.

The biggest take away from my experience was seeing that even when someone’s artistic contribution is historically significant, and they're at a point in their career that appears as though it couldn’t get any higher or more impressive, and where the value and demand for the work is mind boggling, they still suffer anxiety and insecurity regarding their past, and continuing relevance of their contributions.

Also, in being aware of the more recent controversy surrounding Chuck regarding the sexual harassment issues. I would just mention that in the time I knew him, he was devoted to his family and I never heard him regard anyone in a degrading, demeaning, or vulgar manner. I certainly never saw him use his status to gain favor of any kind, only to help others.

Joe Letitia, Shaped Notes Only, 2023, gouache and pencil, 16” x 16”

RB: You describe your childhood home as being surrounded by an “abundance of forest and watershed property.” Did this upbringing/ environment inform your work?

JL: It informed my sense of perception and me as a person. I spent all my time with my best friend or just me and my dog up in the woods from the time I got home from school until it got dark or was time for supper. I would hike out to the ridge that looked out over the reservoir. It was a very typical and beautiful New England vista, which could have been a Hudson River School painting. Actually, Frederic Edwin Church painted this same ridge not far to the south in New Haven. My plywood paintings transitioned into a series of topographic map paintings derived from Hudson River School paintings. Instead of the visual views, I painted the topographic equivalent of the scenes. I found an interesting similarity between plywood grain and topographic elevation lines. The plywood veneer is a single slice out the skin of a single tree, and the elevation lines represents the surface of the earth covered by countless trees.

RB: Have you ever been surprised by someone’s perception to your work?

JL: This question actually dovetails into the previous. My last show at Casey Kaplan in New York, before I moved to Tennessee, was perceived in a way that I certainly wasn’t intending or hoping. In retrospect, I should have taken the advice of my dealer and just sat on the work, and thought more intently about whether to show it at the time. I had developed a reputation with my plywood paintings for a kind of detached conceptual minimalism, dealing with notions of perception and identity. The topographic works leaned in a similar direction, but also explored ideas about art historic lineage (American painting / artists based in New York / non-representational vs. representational painting). The work in that last show was an exploration of identity on a more personal note, rooted in where and how I grew up and became aware of my sexual curiosities and identity as a pre-teenager. The show was based on a series of large-scale photographs I took of trees that were in the forest behind my childhood home. The trees had scars and malformations, as well as places where they fused together with other trees resembling a kind of coupling. As kids we were hyper-aware of them as they were the subject of games and sexual references. At the time and in my mind, these works were a progression from very purged notions of identity, to explorations of identity as an American painter, to a scrutinization of a more personal development and identity. Consequently, the work was difficult for collectors and critics who were invested in my work for its quiet and conceptual basis. On the other hand, there were those who grew interested in my work for some kind of titillation factor, of which I had no intention of provoking.

RB: What are you working on now and what’s next?

JL: I am currently still working with the church imagery. At the moment, the paintings have been getting denser toward the center with less prominent structures that seem to fracture into shards of color. The last several paintings have also been done using gouache and pencil. Also, I have been working on a series of chalk pencil drawings on old roof slates. The roofing slates are 12” x 20” and there are also some smaller slates at 8” x 16”. They evoke early one room school house writing slates or a section of professorial chalkboard notes and equations. The slates are not as smooth as a chalk board so I have had to grind polish them down some.

Joe Letitia, Jesus Cried, 2019, Bible school materials on birch plywood, 8”x 8”

Joe Letitia was born in New Britain, Connecticut on Christmas day, 1960. His childhood home was in the neighboring town of Plainville. There was an abundance of forest and watershed property upon which his home abutted. He attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and Tufts University from 1980 – 1985, and also attended Graduate School at Yale University from 1987 – 1989. He worked and lived as an artist in New York City for seven years, where he renovated a studio in an old factory space in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, to live and work in. During this period of time, he had four solo exhibitions in N.Y.C. and worked as an assistant for the artist Chuck Close as well as the sculptor/ photographer, Sandy Skogland. His work has also been exhibited in Boston, Chicago, and other locations around the U.S. and Europe. In addition to his exhibitions, he has received a Louis Comfort Tiffany Grant in 1995 and two Scholarships for travel abroad. He moved to Knoxville in 1997 after participating in the visiting artist residency program at the University of Tennessee and has been teaching Studio Art and Art History at the Webb School of Knoxville since 2002. He continues to make art and reside in South Knoxville with his wife Sheila and their three children in a 170-year-old log home.

Rachel Bubis is a Nashville-based independent arts writer, regular contributor to The Focus blog, and LocateArts.org Web Manager for Tri-Star Arts.

* images courtesy of the artist