INTERVIEW: LISA BACHMAN JONES

JAN. 31, 2023

INTERVIEW: LISA BACHMAN JONES

JAN. 31, 2023

Rachel Bubis: Your recent exhibition at the Parthenon, The Odyssey: A Retelling (2022), takes inspiration from Emily Wilson’s 2017 translation of Homer's epic poem, and highlights the “hospitality of the overlooked identities that made Odysseus’ long journey home possible.” Were you a fan of Homer before this exhibition?

Lisa Bachman Jones: I was not a fan before, but I was interested in how Homer’s work was a foundation for Greek education. What propelled selecting Homer and The Odyssey for this project was the Parthenon Museum as the site of the exhibit. I quickly became interested in parallels between how artists translate concepts into visual artworks and how Emily Wilson translated an ancient text into contemporary English.

RB: It’s clear you’re very knowledgeable about the characters and nuances – did you do a lot of research?

LBJ: Before reading The Odyssey I read some literature that engages the poem like reading Odysseus’ "Scar", the first chapter of Mimesis by Erich Auerbach, but my research was mainly contained within the the pages of the poem, reading and rereading passages. For more insight into Wilson’s process I watched recordings of lectures she had given.

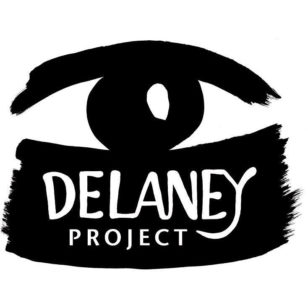

Beautiful, Dreadful, 50 x 36 x 2 in. Spray paint, graphite, yarn, paste, hair, colored pencil, tape, wire mesh, paper.

RB: What was this process like?

LBJ: I entered the process fairly open, prepared to be guided by the text. It was only as I steeped in the story that themes rose to the surface that resonated with themes within my own art practice: interconnectivity and the maintenance of everyday life. I expected to read a poem more directly celebrating Odysseus’ accomplishments and what I found was a detailed account of the many hosts’ participation in a man’s journey home.

RB: Did the creation of this work provide any insights into your own journey?

LBJ: Yes, it did. I was struck by how easy it was to relate to parts of the text that reveal the moral complexity of the characters. And the radical hospitality of the culture was striking to me. Often times Odysseus would be bathed, fed, and rested before anyone would ask him his name. But more personally, it provided a space to reflect upon the complex support system that brought me to my current moment, and who I provide support to.

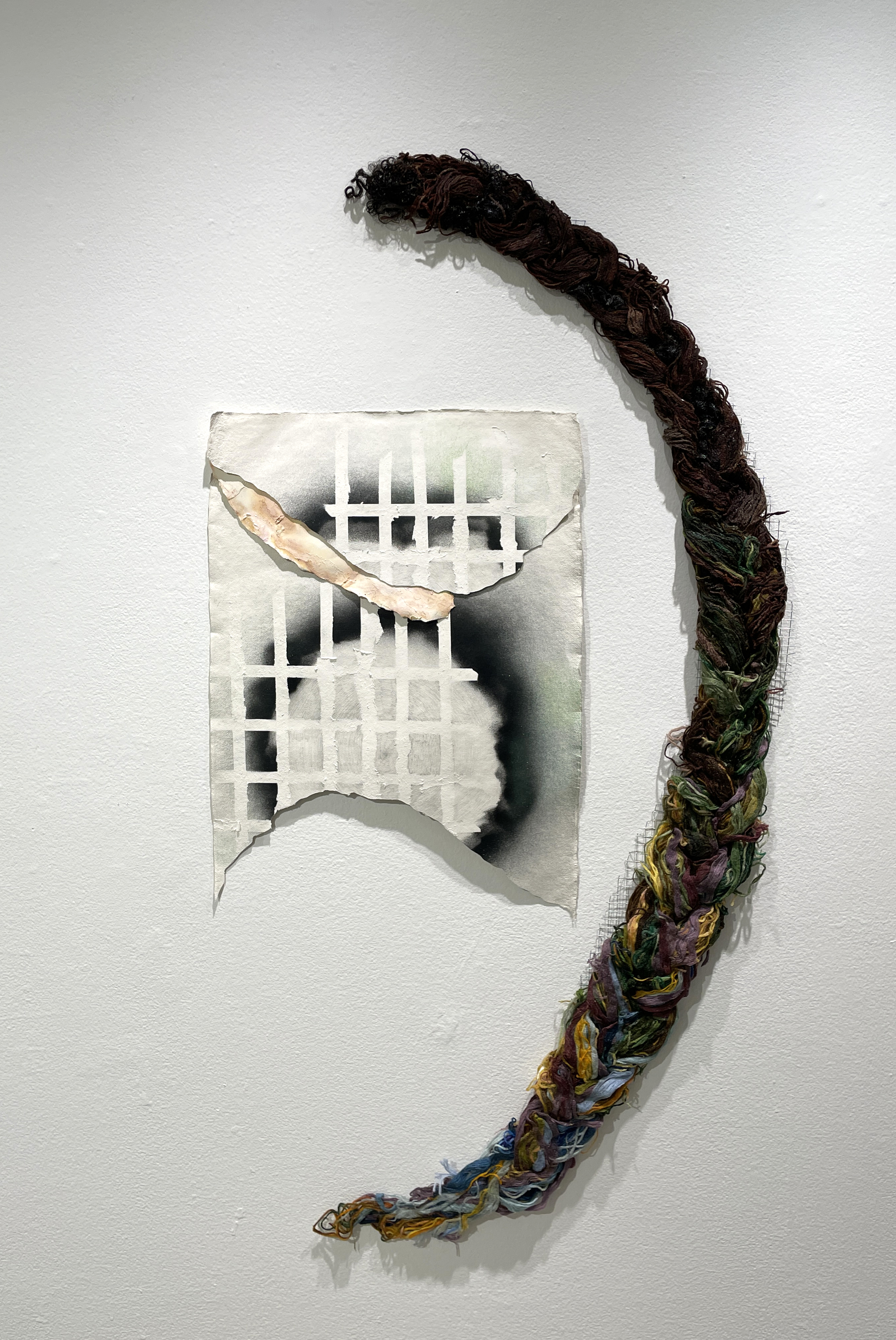

Sacrifice for Athena, 72 x 13 x 12 in. Regrind, wooden dowel, yarn, latex paint, stuffing.

Detail, Sacrifice for Athena, 72 x 13 x 12 in. Regrind, wooden dowel, yarn, latex paint, stuffing.

RB: Can you give an example of one of these “overlooked” hosts in the poem and how they directly inspired a work?

LBJ: The enslaved people in each household were an integral part of the radical hospitality I just described. Each host’s generosity, which they are thanked for would not have been possible without their forced labor. As Wilson addresses in her introduction, The Odyssey is not an abolitionist text. Their forced participation was not questioned nor highlighted by the poem, but it was present. They directly inspired House Slaves, a piece about the final hours of Odysseus’ enslaved girls who are charged with cleaning up and burning the bodies of the slaughtered suitors before seeing their own end. I used a mixture of matte medium and ashes to cover the base. I applied the mixture using a sponge and cleaning motions. Above the the base are five deep red cloths imprinted by a gripped hand. Viewers will find that I incorporated ashes and cloths throughout the body of work to represent the presence and labor of the enslaved people. But for the general contemporary audience, most of the characters are dwarfed in the shadow of Odysseus. His success is perceived as individual accomplishment rather than team effort. Over a dozen elite households, gods, goddesses, enslaved people, and circumstances weave together to make his nostos possible.

RB: You work in such a wide range of materials. Can you talk more about your process in sourcing/choosing them?

LBJ: I let the text guide the materials. I kept a list of them and the objects mentioned. At times I took the liberty to “translate" the ancient thing into a contemporary one and in other cases I stayed consistent with the text. All the while though, I first use stuff that I find, am given or what is discarded. Only when necessary do I buy a material I need because there is an overwhelming amount of stuff that circulates around a city. This way of thinking about and sourcing my materials relates to philosopher Jane Bennett’s arguments in her book Vibrant Materiality.

Blood-Bowl,10 x 12 x 10 in. Paper pulp, acrylic paint, regrind, dog hair, ashes.

RB: Do you collect materials first that inspire you or find them after you get an idea for a work?

LBJ: I work in both ways. And either way, I like to work at the pace of availability: what stuff is available from what is no longer deemed useful. There is a quote from filmmaker and artist Jack Smith that has stuck with me. He’s asked if he can imagine any other types of societies and he answers that one type of society would grow up around a central junkyard where citizens brought their unwanted objects and that this would spark activity. I want to live in this imagined city. In response, I started a free market outside of our house where I place things for my neighbors to take or drop off their own unwanted objects. Working and thinking in this way is important to my practice for a number of reasons. I’m of the mindset that all matter is precious and should be reckoned with (Jane Bennett’s influence again). Whether from the perspective that the natural resources are not limitless or that every commodity involves the spending of those natural resources and the human labor invested in producing the thing.

RB: What does your studio look like?

LBJ: My studio is a long, finished room above a detached garage. On one side are the supplies and the other side is kept fairly bare for installing works in process. I make the works on the floor with tools and materials spaced an arms length away. This way of working allows me to stay actively moving and looking as I make-standing above, laying beside or hovering over the work in progress. This also means that each piece is constructed from a bird’s eye or horizontal view rather than vertical eye view.

Shapes of Athena, 120 x 46 in. Watercolor, wax, graphite, acrylic paint, yarn, fabric, colored pencil, spray paint, ashes on paper.

RB: Is there a material you’ve always wanted to work with but haven’t yet?

LBJ: I like this question, although I don’t have an answer for it right now. Probably because during grad school I took the opportunity to experiment with many unfamiliar materials. Currently I’m focused getting to know textiles, wood, and the readymade better.

RB: In thinking about the context of impermanence and structures…. You’ve been a staple of the Nashville art scene for so long! I’m sure you’ve witnessed a million changes, galleries opening and closing, etc. However, the Parthenon has stood strong! Is there anything you miss? Is there anything new you love? Do you have any hopes for the art scene/otherwise in this town you’d be willing to share?

LBJ: The list is long and not from a position of resisting change, but more questioning the conditions around the changes. Have some art spaces and galleries closed for productive reasons like the lifespan of a project, or have the changes been due to inaccessible rent or lack of funding? I miss the video instillation stalls at Cheekwood. I miss Ruby Green, Tag, and Twist Gallery, and the studio spaces in the Old Hosiery Factory. And I’ll miss working with The Rymer Gallery. I hope that artists, writers and curators persist in identifying what our art community lacks and bring it into being. I hope that we are open to constructive, critical debate about the art we make since cultural and visual production comes with forms of responsibility. I hope that accessibility to the arts does not have to mean consumerablilty. As far as what I love - I love the generosity of Nashville’s artists/community by which I mean in general we share opportunities and resources with one another, we collaborate and celebrate with one another even when applying for the same opportunities.

Telemachus’ Youth, 8 x 12 x 12 in. Construction paper, glue, regrind, silicone, cotton ball, wax, trinket, dried fruit peel, broken ceramic, acrylic paint, foam, twig, plaster, lint, part of an ornament.

RB: In June of 2020 you did a performative act as a way to “see the unseen,” where you walked for 27 minutes carrying what appears to be large light blue appendages made from discarded bubble wrap, plastic bottles, styrofoam, pvc pipe, and plastic bags wrapped in strips of fabric dipped in latex. Were you able to find any understanding from this walk? Did anyone see you/respond?

LBJ: Thank you for asking about this piece. It was a modest performance witnessed by a handful of neighbors and the cars passing by. The walk was a way to access what I had only ever painted up until this time - the internal thoughts and emotions of embodiment, specifically the weight of an internal burden. My plan was to act as if the two appendages were completely normal and if I were to interact with anyone else, I planned to greet them in my normal tone. No one responded other than returning my “hello.” In a sense this did not surprise me. I was adding one more strange thing to a strange time. There was a sense of satisfaction and excitement in performing the piece for whoever happened to be out in their daily life. No fuss, no announcement or signage. There was no data to collect on the impact or reflection of the few temporary audience members, just video documentation.

RB: Have you ever been surprised by someone’s reaction to your work?

LBJ: The times when a particular painting or sculpture resonates with an individual’s so strongly that they’ve had some form of affect - tears, chills, laughter, disgust, blushing - when a work has served as some form of catalyst or conduit for accessing or understanding something forgotten, kept private, or unknown feeling I am always surprised. Even though connection is a goal I have for my work, it never ceases to be a surprise when connection is achieved.

RB: What are you working on now and what’s next?

LBJ: I’m working with the concept of Frankenstein’s wretched: what happens when we making a thing that ends up being beyond our control? What happens when that thing demands accountability from us, its maker? What are our personal and collective monsters? I’m still in the research and sketch phase. And as always, the concept can start to sprawl in to many fields. Its always a challenge to reign myself in conceptually and formally, but it’s a productive struggle.

Where the Earth Hides Him, 87 x 72 x 3 in. Wood dowel, braided yarn, curtain with horse graphic, paper, wax, latex paint.

Lisa Bachman Jones (b. 1983) currently lives in Nashville, TN. In 2006 Jones received her BFA from Belmont University and earned her MFA from Watkins College of Art at Belmont University in 2021. She looks at how the permanence of things shifts over time when we are not paying attention, whether considering a vow, a slab of cement or a collective common sense. By asking questions as a means of tending, Jones addresses social, political and economic issues through her work. Jones has worked with museums, galleries, and educational institutions as an artist, educator, and curator. Her work has been recognized with grants and awards, and has been acquired by corporate and private collections. Jones currently teaches for MNPS, is focusing on her studio practice, and continuing research for upcoming projects.

Rachel Bubis is a Nashville-based independent arts writer, regular contributor to The Focus blog, and LocateArts.org Web + Print Manager for Tri-Star Arts.

* images courtesy of the artist