INTERVIEW: BETHANY CARLSON COFFIN

FEB. 16, 2023

INTERVIEW: BETHANY CARLSON COFFIN

FEB. 16, 2023

Wesley Roden: The scale of your work coupled with the attention to detail allows viewers to either look closely or from a distance. How do you anticipate your works to be viewed and how do you create them with this dynamic in mind? Do you expect the works to be viewed personally, impersonally, or somewhere in between?

Bethany Carlson Coffin: I definitely put a lot of emphasis on the experience and the encounter. That dictates, to a large degree, the format, or the scale of something. Some of that has to do with what I want to capture, and how well I can do it using some of these strategies. In the reductive works, I know the language enough to know what scale something needs for it to be effective in the way that I envisioned. I also lean more towards a more intimate experience. But, I also understand the value of presenting something that could be overwhelming in terms of texture or just an all-over composition. I want for there to be a kind of overall wall presence that lures someone in so I think about that point of entry too. I think, “What is the method by which I can invite someone into this personal kind of intimate space, creating something that promotes stillness…” It’s not automatic. So there has to be a kind of way to get someone into that frame of mind…

WR: Your work seems to balance permanence with impermanence, depicting impermanent plant matter with the same level of magnitude as age old celestial bodies. Do you seek to highlight that contrast, or are you more emphasizing the permanence of nature or even its cycles?

BCC: I think the work is more what you're touching on with the idea of cycles, because for me, it's about the kind of perspective one gets when they realize that whether it's a shorter lifespan or a longer one, that not one thing is determined by me. I don't have control over that, whether it's this one day life cycle, or a 1000 year cycle or whatever. We can’t try to comprehend it. So to me, it offers perspective to think about all of these moving bodies of matter and life that have had meaning and purpose, not because I have anything to do with controlling it, but just because I'm appreciating what life looks like. I'm a part of that, and you're a part of that. So it's for me a way of offering some perspective that can be really meaningful, particularly when someone's going through grief, or anxiety, or some kind of health issue or addiction. We're all a part of a larger moving picture. And so I think I'm trying to connect (the viewers) all on that level.

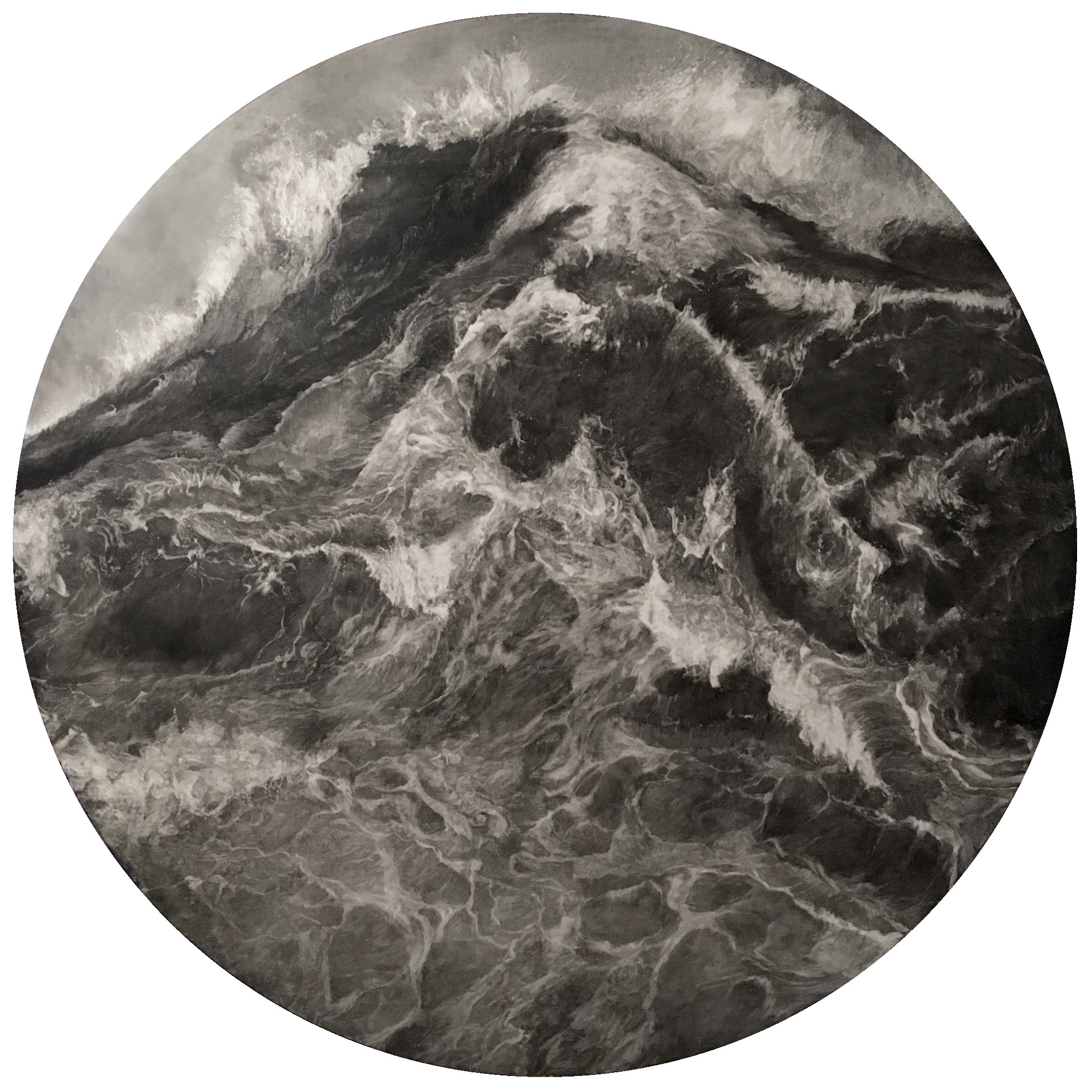

A Mingled Song I, Charcoal on panel, 48” diameter, 2018

WR: Your work sometimes centers the subject matter on either a square or circular frame. Do you make this decision to contrast the organic forms or to emphasize symmetry or unity in the work? Do you seek to evoke a lens maybe belonging to a window, telescope, or some form of apparatus?

BCC: Absolutely, I do. I definitely use a lens or the idea of a frame. I think that goes back to what we were talking about earlier; a kind of point of entry. I do use focal or radial lines sometimes referencing a telescope or a camera to further emphasize the idea of a place to focus. Then, with the liminal animal pieces, it really started with my recognition that if I wanted to commemorate or bring dignity to these (dead animals), then I needed to respond to them. And I wanted to make sure that there was still some kind of geometric stability. But the circle lent itself better to some of those forms, and I wanted my space to conform to that need and conform to that body. The compositions and the formats are always in service to the concept and the subject for me. And if I'm placing something right in the center, it's because I want there to be this kind of centralized stability to it.

(Planetary bodies) are so different from those animal pieces, because they're so unreachable. So it seemed important for me to have that other element. And that connects us to it, the actual lens of trying to see it, because things that are in our physical world, down here with us, we can reach them. But those (planetary bodies) were particularly compelling for me, because we think they're so hard to reach; they're so hard to comprehend. You can imagine that you're being fooled, that they aren't real. So, I felt like there needed to be that extra link. I added (the crosshair in Philae Sleeps), because the image itself didn't quite link to the viewer yet in a direct way. And then, what I was fascinated with when looking at those images was that there is a part of it that is photographic documentation. These spacecraft were the ones photographing and that was a part of the imagery. So there was a direct reference in the images to the thing trying to document. So I felt like that was the right method to link it right there, growing it together.

Philea Sleeps, Charcoal on panel, 34” X 34”, 2016

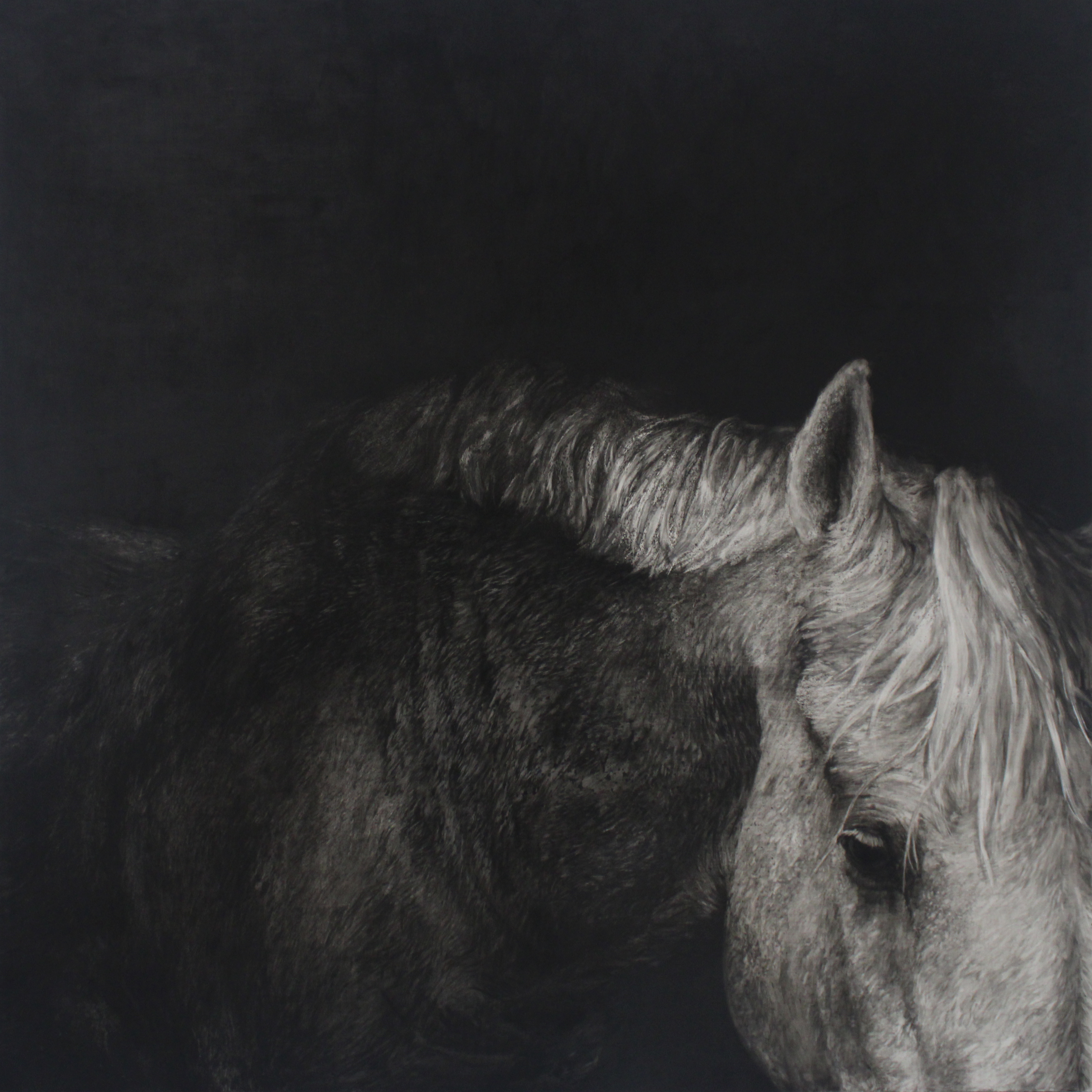

WR: An aspect of your work is detailing the intangible, with the inaccessibility of planetary topography mirroring the intangibility of memory. Do you see this as a change of direction from your previous, more intimate subject matter, such as foreheads or animal fur? How has the level of detail changed form or taken on new meaning as you shift in subject matter?

BCC: I think for me, it's a different approach to different forms of grief, and the way that we are, as humans, forced to grapple with it. Not all forms of grief are the same. Sometimes, the memories and the loss are very intimate and very personal, remembering someone's hair, someone's smell, a particular smile, a particular accent, or the way they said certain things.Those are part of intimate moments that you shared with someone. But then there's other forms of loss that are more about what never will be, what never came to be, or the recognition that a person, thing, or opportunity was never yours. So that's a very different kind of loss, because it's not about the tangible thing that has left a void, but about the thing that will never be or that you will never know.

I realized that different subjects lent themselves to different forms of grief. And so hair, the very tangible and tactile things, were about those intimate memories of what was real and very tangible. And then I was just missing that void. But the void, unknown or unanswered, is an interesting thing. Because the more I'm in those spaces, looking at different forms of grief and different forms of loss, what has become evident, and what may be more of my focus in current and future works, is the idea of ownership dysfunction. What is really ours and what isn't? Because when something is lost, it feels like we personally have lost something. It causes us to question what we owned, what was ours in the first place. I think there is a distinct difference. But also, there's some similarities in terms of my approach, because it's all about grief and loss and how one reconciles those things on various levels. They just look very different depending on the nature of the loss itself.

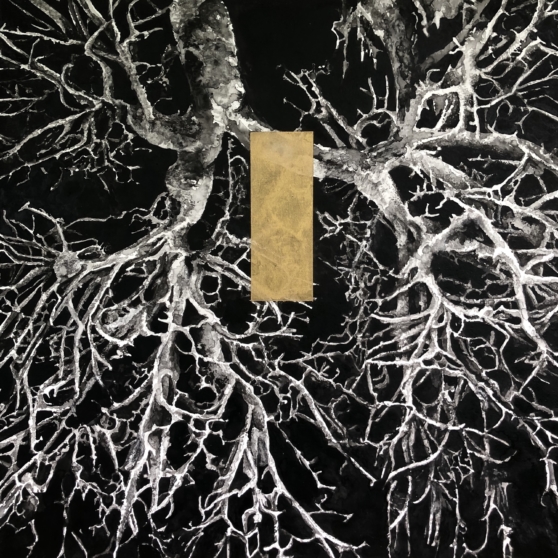

Days From Now, Graphite on Panel, 54” X 6”, 2016

WR: Your work often plays with eliminating context, with works from Liminal Eye featuring closeups of fur made indistinguishable from the animal itself. Later works simply fill the entire frame with the subject. In your choice of whether to show or not show, do you hope to obscure the subject matter, warrant further investigation, or some form of both?

BCC: I definitely think it's a little of both. And this is probably a good follow up from the previous question because it does go back to different forms of grief and approaches to grief. But in this regard, I think it also has to do with perspective. Oftentimes, we can be so close to something that we can't fully see it. So when I choose to fill up a space, I'm usually thinking about the idea of being so close to something that we don't really have that objectivity. We only have this really close, overwhelming view of something. It's all encompassing. Grief can be like that. Anxiety can be like that. It just fills up, and we're just too close. There can be a kind of proximity issue.

But then in other spaces, I think it's not the overwhelming amount of information and closeness, but the obfuscation of what we see. We only see so much at a time. And I'm also interested in the way that life is lived one sliver of a moment at a time. All we get is that one moment to the next moment. So that's the other mentality that I have when thinking about space. (I ask) if this is overwhelming or all encompassing? Can I see around it? Or am I only getting this part of life at a time? Is this all I can process at once? Sometimes, It's like that flashlight in the dark, where it's just one portion at a time. I love that black obfuscated kind of murkiness or that tunnel prism. (It’s like) this is what I can see right now; this is what I can deal with.

WR: You have worked previously in sculpture and installation for your series, Fathom. Do you ever plan to revisit your past floral arrangement sculptures or create something new? If so, would working with physical objects be more or less constricting?

BCC: I'm very much a painter, drawer, and 2-d artist. I don't want to fight that too much. But I really do try, with every concept, to ask the critical questions such as, “What should this actually be? What should the encounter be with it? What makes sense?” To always default to a painting or drawing is not good practice. There are so many times when I've fallen into that trap, where I've had this idea that isn't coming together only to finally realize it doesn’t belong as a painting, it shouldn't be a drawing, it should really be an object, or it should be something else. So I try to make that a part of my practice, even though a lot of times, when I am making drawings and paintings, I don't want to have that conversation with myself as part of the process.

So for a while, it did make a lot of sense for the pieces I was making to be physical, sculptural objects or to be installation. I had a relationship with a florist in Illinois, where I would pick up, once a week, discarded flowers. So it became a practice to dry them, sort them, and do things with them. That was great, because it kept me working with the materials until I found the solutions for them. It was something I sought out because it made sense for my ideas.

I would really like to get back to doing some sculptural work, but I’m focused on the pieces that make sense as drawings and paintings because it's what I can accommodate with my current studio situation. I also have a lot of ideas that are probably on a back burner because until I have the right means, materials, and solutions for executing them, I'd rather just not try until I know the way I want it done. So sometimes those decisions are a bit practical. You're looking at what you've got, what you can do, and what makes sense. But I really don't try to force an idea into the wrong form. That was just a time that was great for me because I was able to engage with the materials, work with them, and figure out what I wanted to do.

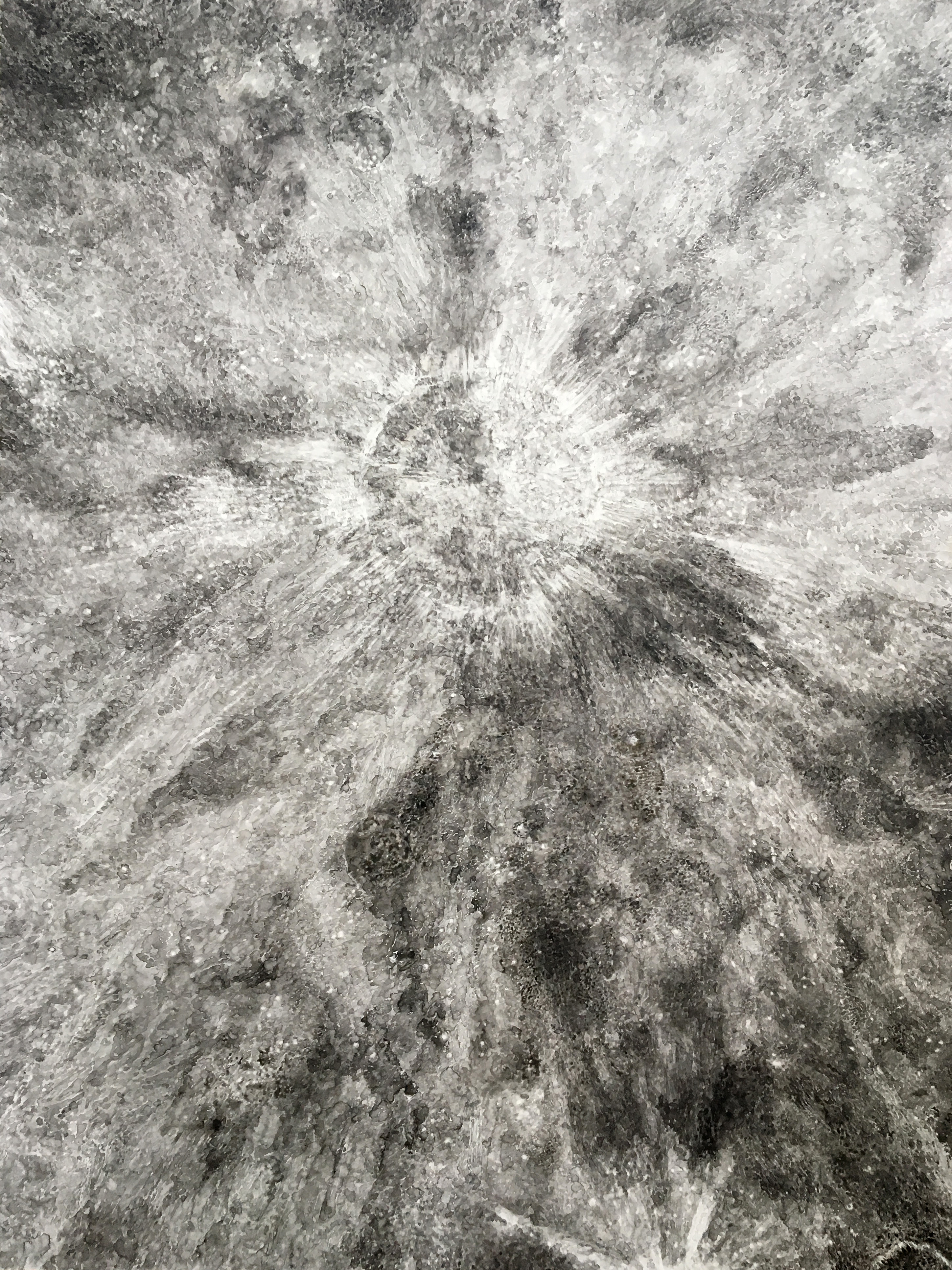

Moon Blindness, Charcoal on panel, 45” X 45”, 2022

WR: In each series, the works explore consistent themes across a cohesive visual language. Do you see each work as a whole in itself or as part of a bigger picture? Is that bigger picture ongoing, and if so, when is your work complete?

BCC: Definitely the thematic explorations are ongoing, I think I do see them as part of a larger connecting series of ideas, continuing to explore grief and ways that one processes with funeral kinds of ceremony. But I think there's lots of room in there. I don't see myself running out of ideas, but I can see myself revisiting some of the language. I can see myself returning to hair and texture, and I can see myself returning to some celestial body pieces. I can see myself even returning to some of the painting techniques I used to use that I haven't maybe in 15 years. Even right now I find myself painting a bit more than I used to. And so I do think that I will probably cycle back. There's things that reemerge, and I realize, “Oh, this is really more connected to what I was doing in the Moon series,” or “This is really more connected to what I was doing with the liminal series.” And oftentimes, at the end of producing a body of work, there'll be a couple pieces that are really more precursors to the next thing. They connect more to where I'm going. There’s always a trail. And I'm following it around and it's probably going in some circular motions. I don't really exhaust something and move on. I just follow where my ideas are taking me.

Art making for me is not really a romantic thing. It's really more of a discipline. The only way that I can maintain that discipline is to follow where things are taking me. I've found that I can't force myself to linger too long somewhere where I've explored this thing, and until I discover some other things, I won't be able to come back and appreciate it. It's like when you travel a circuit or you revisit the same place every year, which is actually something our family does. We have gone on the same vacation every year for 30 years. You can go to a safe place, before you can come back and re appreciate new things about that same place. I feel like that's my travels, to go away and come back and go away and come back.

Becoming, Ink on Clayboard, 18” X 24”

WR: How has teaching and community involvement influenced your work and what you hope to achieve?

BCC: Teaching is so healthy for me, because it keeps me thinking about why I'm doing what I'm doing. If I'm asking my students these questions, I have to ask myself these questions. It gives me a sense of accountability but also reminds me of these foundational things that I want them to learn. How do I remain diligent? How do I ask the right questions of my work? (These questions) are so valuable. I also love having that relationship with them, and the community as well, because I think art making can be really strange, self-serving, and closed up otherwise. And so, being a part of a community, doing projects with other people, helps remind me that it's not all about myself. It helps me keep open and try to consider what else my art making can do, how it can function beyond me. Just being in the community, doing bigger projects, doing community projects, or working with a group or an organization helps get myself out of the space where I'm making just for me, and it feels like it's just about me. (Teaching) is really healthy for me to maintain some perspective.

Bethany Carlson Coffin is an artist and teacher currently living and working in Chattanooga. Bethany has lived in Tennessee three years, and is currently faculty at Cleveland State Community College. Focusing primarily on drawing, Bethany also makes installations that relate to her often delicate, pensive, and funereal artworks. Bethany is dedicated to art as a field of study and to community involvement that both educates and enriches lives.

Wesley Roden is the Lead Intern at Tri-Star Arts, completing his BFA in Painting at the University of Tennessee, School of Art (anticipated: May 2023). Based in Knoxville, he currently works in digital and mixed media in a continually evolving practice.

* images courtesy of the artist