INTERVIEW: ASHTON LUDDEN

SEP. 21, 2022

INTERVIEW: ASHTON LUDDEN

SEP. 21, 2022

Rachel Bubis: You mention that your prints "explore our relationship with other living creatures as we become further removed from the natural world.” How did your passion for animals and the environment first begin?

Ashton Ludden: I think we all first have that fascination with animals and the wild world when we are children. For me, I’m sure it began in my young childhood, particularly when I was between 2 and 8 when I lived out in the countryside of Western Missouri. I grew up around many animals - whether it was the family dog or cat, the horses, the reptiles and fish brother would catch, the barn cat and her kittens, or the neighbor’s chicken, cattle, and buffalo - animals outnumbered us. Although it sounds typical to recall a childhood spent outdoors, I did spend most of my time outside playing make-believe, imagining interacting with all of the woodland creatures, which were instead easily hiding from this curious and loud child in their space. I think these experiences just stuck with me because I was exposed to nature in depth as a young child, and for years at a time. I think a lot of us sort of lose that innate attraction to nature as we age or maybe we are simply distracted with other life matters - a lot like we all have a natural interest in art and drawing as a child, but quit as we get older too.

When I was in college, it was the first time in my life when I considered the food I ate (meat in particular) and how it came to get onto my dinner plate. This thought opened a floodgate of hands-on research for my work regarding our relationship to domesticated animals, particularly our food animals. (See Meatimals™)

"Mondo - rhino conservation project" various prototypes of ceramic pieces made from skin molds of a living rhino, 2020

RB: In your Rhino Conservation Project in partnership with Zoo Knoxville, you designed textured ceramics to create funds for their Species Survival Plan and the International Rhino Foundation:

“The texture on these slab-built ceramic pieces are a print of the skin texture of a 5,200 pound, male, Southern white rhinoceros named Mondo. The skin texture molds were created back in 2016 using non-toxic alginate (the same material used to make teeth molds in dentistry).”

Can you tell me more about the process of getting this skin imprint and translating to ceramic?

AL: I worked with Melissa McGee - Lead Keeper and Mammal Coordinator of Zoo Knoxville - to carefully take molds directly from Mondo while he was in the rhino barn. Her and I were behind large steel columns to keep us and the rhino safe, but we were able to hang out with Mondo, feed him treats while I plopped the alginate mixture – a liquidy, non-toxic skin-safe mold making material – onto various parts of his head, neck and shoulders. These were the only areas of his body I could reach without entering his space. Then, after a few minutes, the mold hardened to a rubbery solid, easy to peel off - similar to Silly Putty. The alginate has a short lifespan and becomes fragile and brittle, so I took them back to my studio and made strong, porcelain molds from them, so I can use the molds over and over again to create casts with clay.

I made a variety of items using this mold such as mugs, cups, bowls, and some jewelry. I wanted to physically and metaphorically bring viewers closer to wildlife as they handle and “touch” a real, individual rhinoceros in their own home, particularly one they saw maybe only a few miles away from their kitchen. It is not a generic print of some rhino or a representation of rhinos, but one specific rhino that they saw with their own eyes and can now physically experience a literal replica of them. Could this realness of touch be the stimulus that produces an emotional response or reaction to this animal? To its threatened existence?

Sometimes I ask myself, why should anyone really care if a rhino goes extinct? Would it really make a difference to us? Then I recognized zoos are likely the only place where people ever experience some of these endangered species directly, in real life. Is there something important that happens when we experience this animal in front of our eyes, rather than in a book or on a high-def screen? Can one extend some of that experience from the zoo, back home to help incentivize us to take real actions to aid the survival of these unique animals?

What was unfortunate was Mondo has since passed on since I made these pieces. What is fortunate, is that Zoo Knoxville and others who purchased the ceramic pieces now have a physical archive of a unique individual rhinoceros named Mondo that existed, and they can touch and hold him forever.

I wish I had photographs to share with you to help people better understand this process, but we didn’t have anyone documenting it at the time. This was a unique, side project I pursued to just play and test some things out. It will possibly continue in the future with other rhinos and other species.

RB: How did the Zoo Knoxville collaboration come to fruition?

Working with a non-profit such as Zoo Knoxville has been rewarding and educational. The rhino project was somewhat organic over time, where I gradually got to know some people working there and had an idea then proposed it to them. This past spring, I was then asked to paint a native pollinator mural for them as well. There is an obvious kinship between us with my passion for making work about issues in wildlife and their mission to educate the public about these magnificent creatures on our planet. It is enriching to work directly with experts and scientists on the subject matter I create. I hope to work with Zoo Knoxville more in the future on other projects that help educate and support the survival of vulnerable animals.

"Mesodon thyroidus" wood engraving 2021

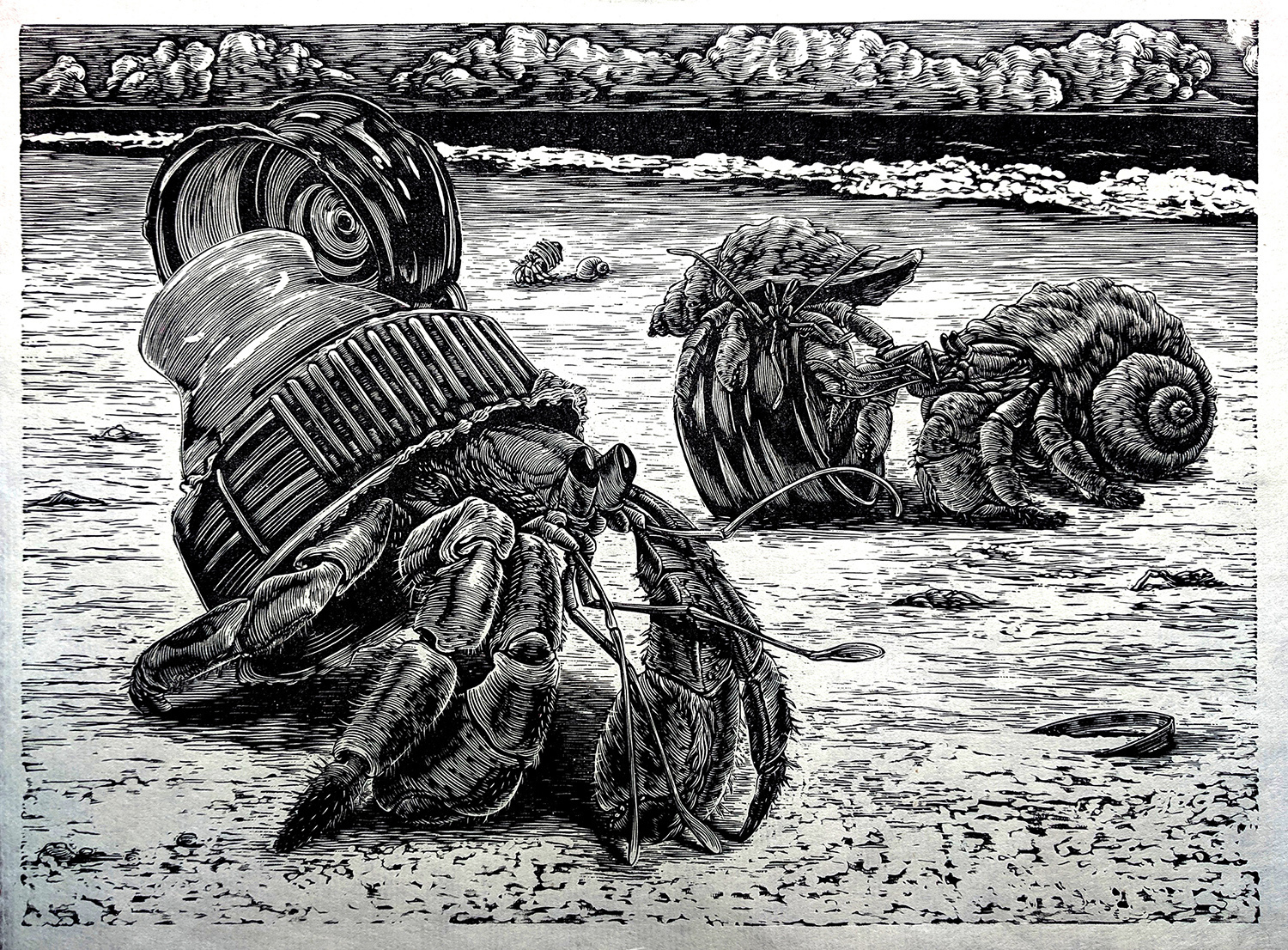

"Upgrade!" Resingrave relief engraving, 2019

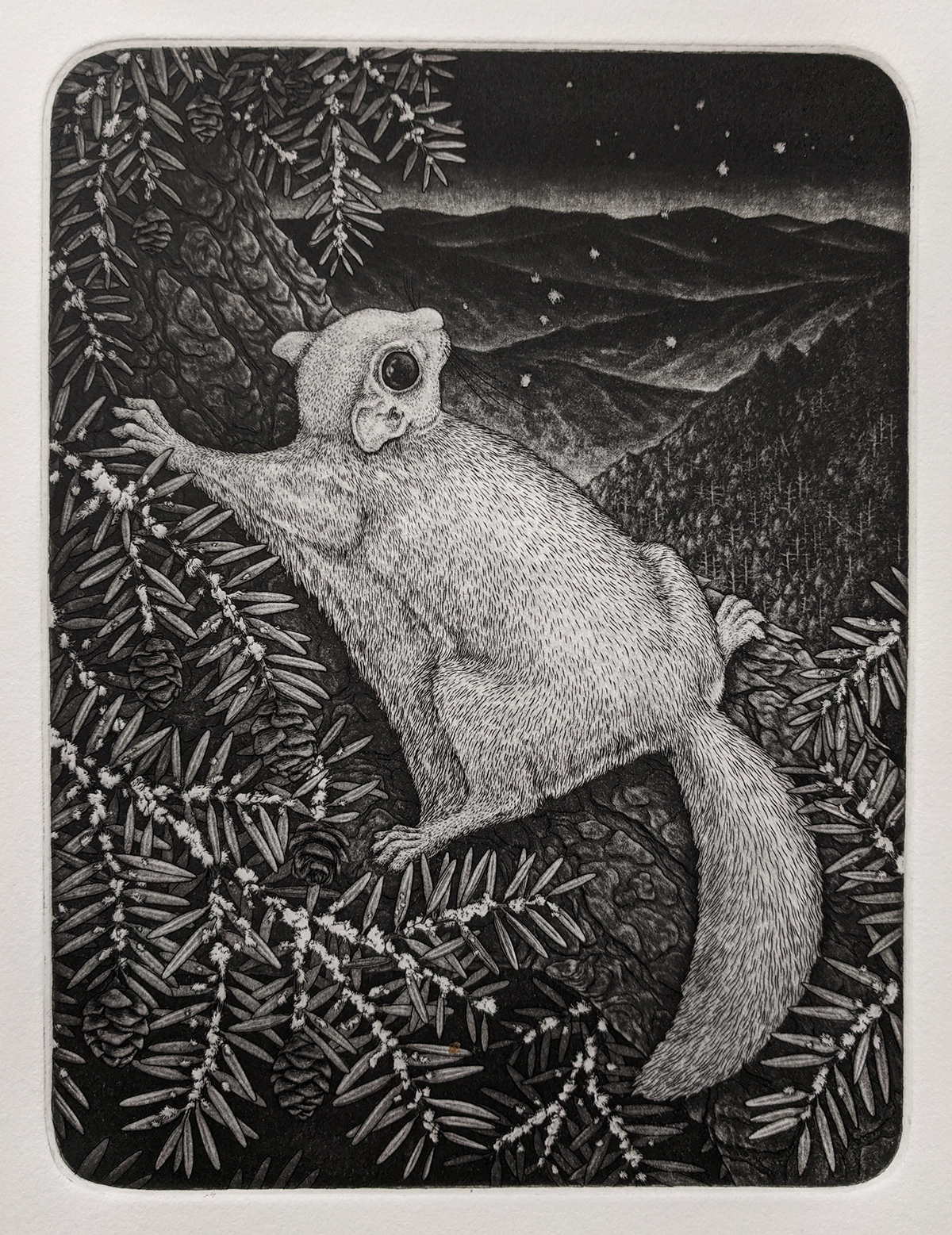

"Woolly Bully" copper engraving with aquatint 2021

RB: Traditional hand engraving seems very meticulous. Is it tiring? meditative?

AL: It can be tiring for your eyes, but like any other process, taking breaks often helps manage fatigue. Hand engraving is a very slow, intimate, and quiet process and requires concentration and patience. These qualities make it a peculiar method to create intaglio prints because, for anyone that knows me, those qualities are quite literally the opposite of me as a person.

It can be meditative, but that is simply a pleasant by-product of the process, not necessarily my drive to do it. I have always been attracted to detail; I’m easily lured into investigating things closely in my environment. Engraving allows me to get lost in these small spaces because this carving process is able to hold vast depths of detail in the wood or metal you cut.

I originally learned this technique from master firearm and jewelry engravers. We engraved primarily on harder metals like steel and worked on a very small scale using microscopes. So once you see your engraving lines under a microscope, your level of awareness to craft and detail becomes quite heightened, which is probably why I perpetually get caught up in my line work... or anything I do for that matter.

Considering my current work on threatened animal species, it is peculiar that I was introduced to my favorite, most utilized process - engraving - by artists using it to instead glorify the sport of hunting animals through tiny, embellished (hunt) scenes depicted on the very object used to take an animal’s life: a firearm.

RB: What was it like working in such a large scale for the Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts mural?

AL: The mural at Arrowmont was the largest artwork I’ve created. It was really fun to use my whole body to create a piece and interesting to work at that scale. Even working quite big, I still couldn’t help myself from painting tiny life-size snails, salamanders, and beetles hiding throughout the 45 feet mural. This mural depicts native cave and nocturnal animals of Appalachia found in the Great Smoky Mountain National Park located a mile from Arrowmont’s campus. Viewers can enjoy discovering over 25 native species of plants and animals hidden within this night scene.

While I was painting this mural, I was also working on an ambitiously detailed copper engraving, but at a fraction of the scale (about 8” x 10”). This print also depicted a dense vegetation of flora and fauna and I was playing with hiding small surprises throughout the work too, such as an invasive chicken or a tiny covid-19 virus. It was insightful (validating?) to recognize myself doing this on both scales. I would like to continue exploring this idea of hide and seek, discovery and play within my work... even when it might be something you don’t necessarily want to find.

Ashton working on Appalachian flora and fauna mural at Arrowmont School of Arts & Crafts in 2020

RB: Are you still developing work that focuses on issues specific to East Tennessee region? Have there been any developments with the North Carolina Flying Squirrel?

AL: I was creating a series of engravings and monotype prints about plastic pollution in the world’s oceans, dealing with whales, sea turtles, walrus, and seahorses, but I wanted to shift my focus on issues in areas where I live, such as the polluted waterways of our complex river system or other current environmental concerns in Appalachia. The squirrel print (an engraving with aquatint) is really about the eastern hemlock tree and it’s struggle to fight off an invasive adelgid, which is in turn removing habitat from other species such as the North Carolina flying squirrel.

My most recent engraved prints have been simplified to be only about small moments I find hiking in the Cumberland Plateau, this helped me work through the early parts of the pandemic and was also used as an excuse to revisit working with endgrain blocks for wood engraving as opposed to alternative plastics like Resingrave or HIPS.

I hike a lot. I take pictures constantly without thinking. I wondered, why am I taking these photos? What am I attracted to? So I used these photos to recreate the small moments I would find hiking. At the same time I’m taking these harmonious scenes in nature, I also document trash and other litter from humans in these wild spaces. In some of these wood engravings, I began hiding litter within the leaf litter. Most probably won’t notice it, but I think it echoes our own awareness of things in this world. There is a real eco-fatigue affecting us, so it can force us to limit what we can focus on. What do we notice? What do we ignore? What do we decide to pay attention to? What are we able to pay attention to?

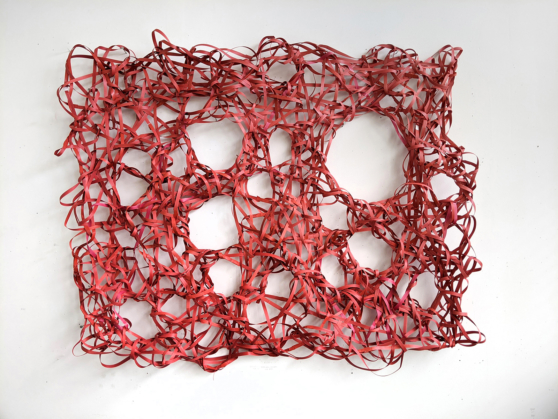

"Plastic Seize (II)" salvaged box plastic straps, 2020

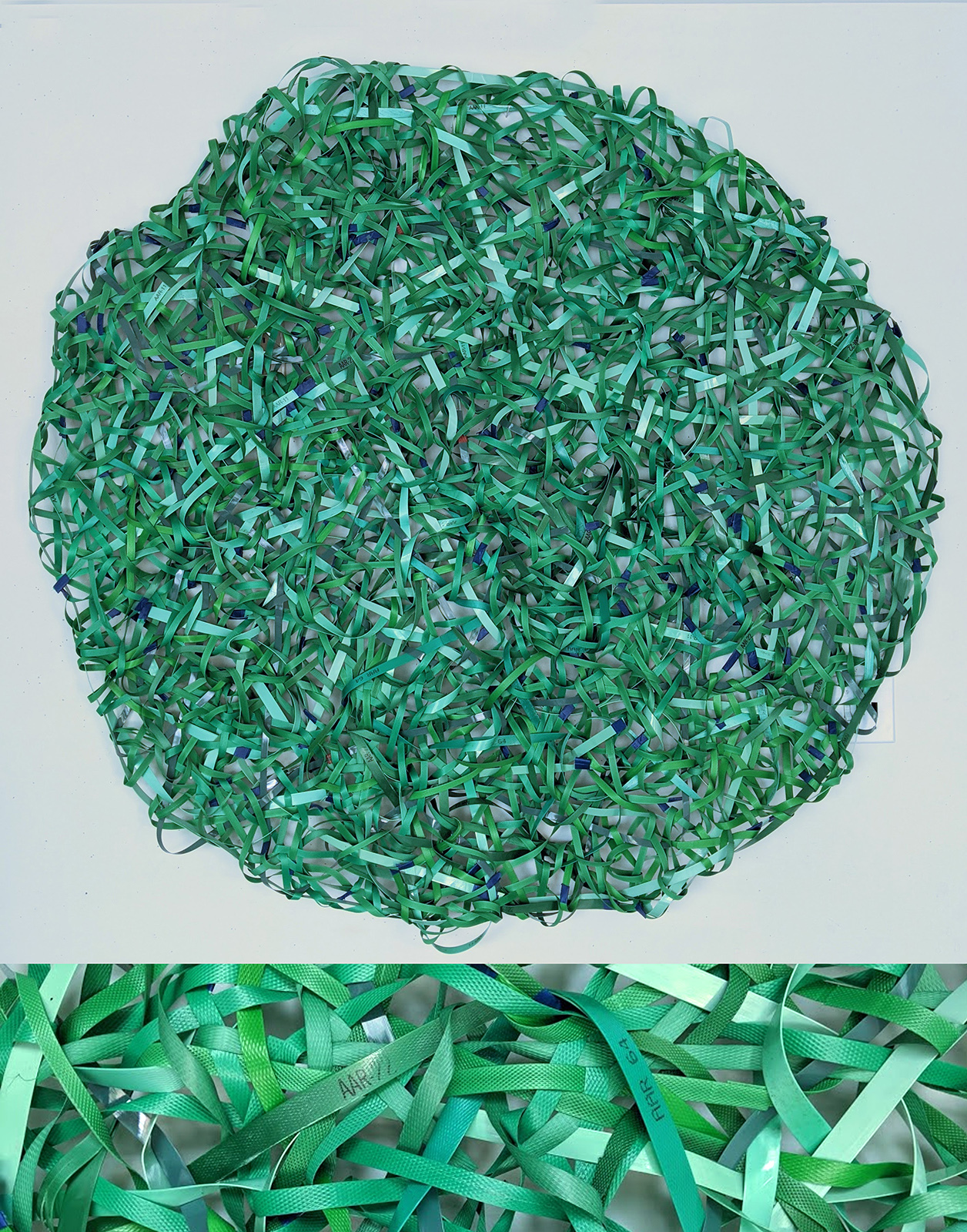

"Plastic Seize (III)" salvaged box plastic straps, 2020

RB: In addition to being employed by Trader Joe's as a sign artist, you independently create plastic weavings from collected salvaged box band straps. How does this weaving process compare with your engravings?

AL: I look at this newer body of work and process of creating as a means to investigate similar ideas but in a completely different way. While I was the lead sign artist at Trader Joe’s from 2014 - spring 2022, I would spend the first hour or two of my shifts helping the store open by bailing boxes, collecting plastic wrap from pallets, organizing plastic buckets and other things we could send back to the warehouse to reuse, city recycling, or send to landfills. I recognized the box band straps, which were only on a handful of TJ’s products, weren’t recyclable but crew members kept trying to recycle them.

I ended up performing a “tasting” presentation for our crew that instead spoke about the company’s current sustainability practices and also about what we can and cannot recycle with the city’s recycling system. It was insightful for all of us and made me hyper aware of the broken wishful recycling system that exists in the U.S. and how it fails miserably. It also highlighted the distance between consumer and the producer and the accountability of excessive waste that has been lost over time.

So basically I told them all to just give me the box band straps and I would keep them forever in my studio instead of in a landfill. My fellow TJ’s crew members helped me to collect these for over a year and I organized them into colors and palettes. The weaving themselves are linear and intricate like my engravings, and they also take time to create them, yet are instead large with bold presence. I see them as tangles of long plastic fibers, which mimic the final shape many plastics take once they reach the ocean. On the other hand, I can also see them as filters or nets... but do they catch more waste or catch unfortunate passerbyers? This very different approach to working has been refreshing and is curious to me to execute more contemporary abstract work alongside my traditional craft of the engraving print process.

This fast-paced, commercial job was a valuable experience for me as a fine artist, particularly as someone who works slowly and meticulously. Many artists, including myself, also teach art in some capacity to financially support ourselves. This was a fresh change to work in production rather than education, but also I was now creating commercial “art” rather than fine art. It definitely had its pros and cons, but overall was a fun job with a comfortable balance of artistic freedom within the store’s parameters and needs. If you’ve ever shopped at their stores or read their Fearless Flyer, you might understand their quirky humor. I quickly learned and applied their play-on-word/tongue-n-cheek style to my signs and enjoyed the silly, lighthearted yet intelligent approaches for selling unique, delicious food items. Another benefit of this job unlike education is that I could clock out and leave work at work. So I could go to my studio after work and create my work influenced by the marketing language I used at work, but apply it to issues in wildlife. Could I advertise to people to give a shit?

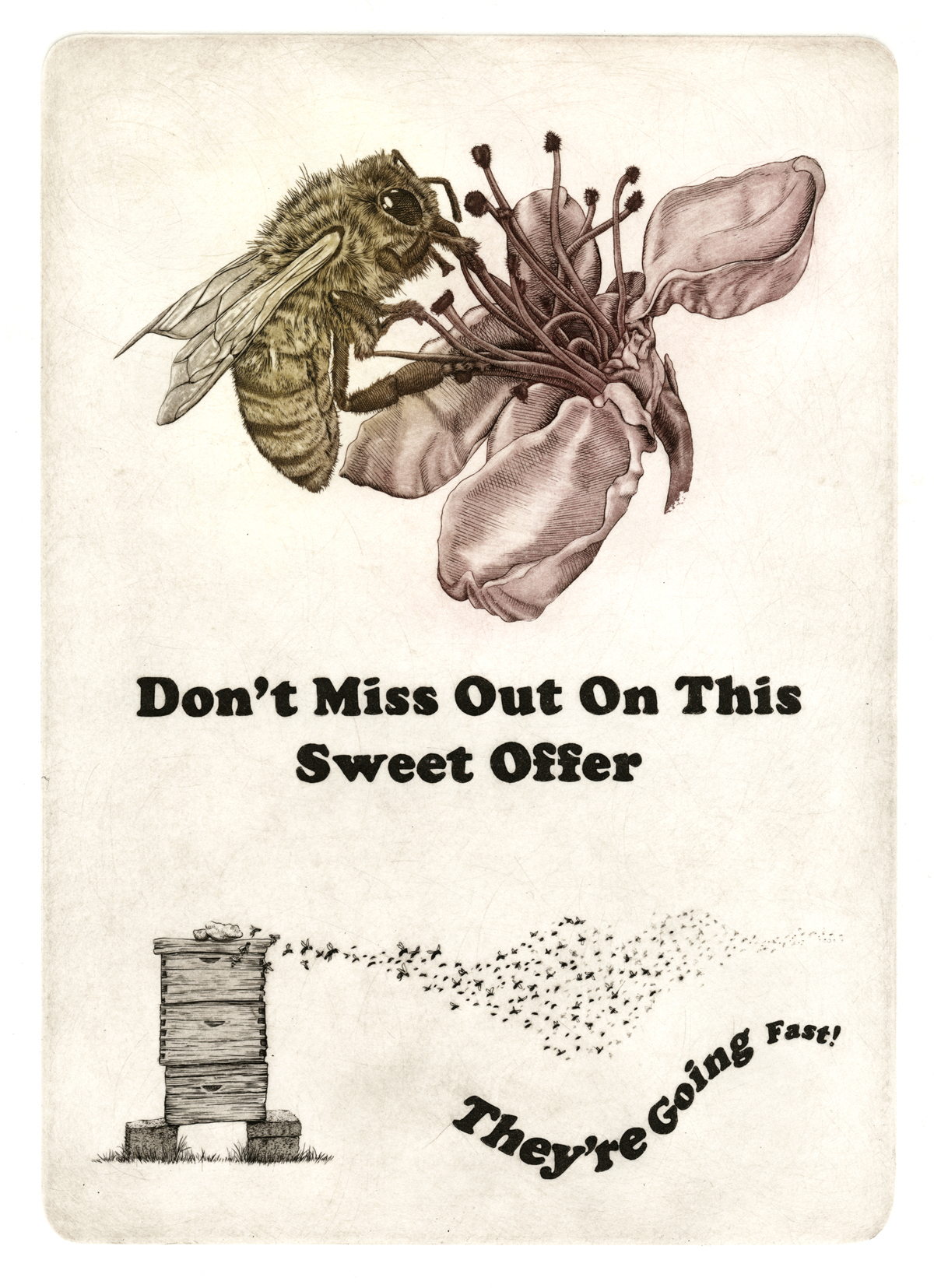

"CCD (Colony Collapse Disorder)" copper engraving with aquatint and à la poupée, 2014

RB: You and your partner recently opened a collaborative artist space in Knoxville called Relay Ridge. Can you tell me more about it?

AL: Relay Ridge officially opened in October 2021. We have 8 resident artists with private studios, a gallery, and we are currently finishing up building a community printshop. We are having a GRAND opening in October 2022, you can find out more information on our Instagram @relay_ridge and at www.relayridge.org.

Ashton Ludden is a printmaker, educator, and sign artist. Her prints explore our relationship with other living creatures as we become further removed from the natural world. As she researches human impact on endangered animals, Ludden develops images of wildlife coping with humans’ influence on their livelihood.

Rachel Bubis is a Nashville-based independent arts writer, regular contributor to The Focus blog, and LocateArts.org Web + Print Manager for Tri-Star Arts.

* images courtesy of the artist