INTERVIEW: NUVEEN BARWARI

SEP. 28, 2021

INTERVIEW: NUVEEN BARWARI

SEP. 28, 2021

Rachel Bubis: Through language, imagery and subject, the act of protest is a big part of your work. Have the events of the past year affected your perspective or practice?

Nuveen Barwari: Unfortunately, not much has changed. The only thing that I think has changed a little is the fact that a lot of us have been thinking harder about where and how we can contribute best and that doesn’t necessarily always have to be through the arts. Just because you don’t make “political art” doesn’t mean you can’t get involved in different ways. Before the pandemic I started writing this children’s book for adults about this character named “Azad” which means freedom in Kurdish. Azad is a tailor who sews and stitches clothes for the freedom fighters in the mountains. There’s one part in the book when some people ask Azad, “Why aren’t you fighting?” and Azad says, “I am fighting. I help fight with my needle and thread.” I stopped writing this book, but might pick it back up later.

The imagery that I use in my work will often function as memorial pieces or as collecting evidence. When you are sourcing images that directly documents the atrocities of a group of people suffering, you inherit a heavy rug that holds a collective weight that is not yours alone to bare. For example, in 2020 I made two memorial pieces. One is titled, The death of a peace maker [above]. The title is from this short documentary I watched on the BBC about Hevrin Khalaf. Khalaf was a Kurdish politician and a women's rights activist. According to the BBC, “She once suggested that every internally displaced family be given a small tree to plant in front of their tent at the camp so that, "after they have left... it will be a beautiful green memory in a land that has grieved them and made them homeless."

Nuveen Barwari, NATO's Turkey Strikes 8 Children in Kurdish Region of Syria, mixed media, collage, found objects, fabric, lace, ribbons, acrylic paint, rug cut out on wooden panel, 24" x 24", 2020

She was brutally executed by a branch of the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army on October 12, 2019, when Trump gave Turkey the green light to go into Syria and start its ethnic cleansing campaign. Khalaf's death was one of many during Turkeys Operation “Peace” Spring. The other memorial piece that I made is titled, “NATO’S TURKEY STRIKES 8 CHILDREN IN KURDISH REGION OF SYRIA,” which both the title and image were sourced from this article that my husband wrote. These horrific events happened in 2019 but we carry them with us, they don’t go away, it doesn’t stop at the headlines. These headlines are just the beginning… thousands of people are still displaced. Nothing has changed. At the end of that short documentary Hevrin Khalaf’s mother talks about how, after her daughter was martyred, Kurdish women would name their children “Hevrin,” she told the BBC, “I can now say I have more than one Hevrin and I will have more.” The idea that martyrs never die, and that they multiply is consistent in the way I make and think about my work. From one piece of fabric, I can create multiple pieces. We are all cut from the same rug.

I saw a video on Twitter of an undercover police in Turkey removing the Kurdistan flag off politician and scholar, Kadri Yildirim’s tomb at his burial in Amed (Amed is the Kurdish name for the city of Diyarbakir, that is in the region of Kurdistan, that is occupied by Turkey). This is an example of why most of the burials and memorials in the region will have all the colors of the Kurdistan flag which are red, green, yellow and white in flowers, ribbons and lace but almost never the flag itself. These colors are symbolic and informed the making of these two memorial pieces.

Initiating solidarity across our suffering communities to overcome the brutality imposed by the discriminatory system is a start. Collaboration and conversation have become more and more important to me. Helping build and nurturing this art ecosystem/community that we exist in especially here in the south also feels very precious to me now.

Nuveen Barwari, Flaming Hot, rug cut out, Hot Cheeto bags, thread, 20" x 27", 2019

RB: You use a variety of materials ranging from Hot Cheeto wrappers to Kurdish textiles to examine the “in-between of cultures,” such as in Flaming Hot (2019). Where do you get your textiles from?

NB:I get my textiles from multiple sources. Some of the textiles I use have been in my family for as long as I can remember. When you go to Kurdistan and come back, it is very common to gift fabrics to your friends and family so they can turn it into Kurdish dresses. My mother, Sabiha Barwari, says that depending on the width of the fabric, all you need is 2 meters to make a Kurdish dress, that is if the width of the fabric is big. You could make a dress out of just about any fabric. I noticed that my family had an excessive number of old rugs, fabrics, and Kurdish dresses stored away in boxes and suitcases. So, I figured others in the community would too. I put out a call on various social media platforms for traditional Kurdish dresses and rugs and have been collecting them ever since.

In Sharon Louden's book Artist as Culture Producer, the artist Jean Shin described her relationship to collecting materials from a larger community in the following quote that really resonated with me:

“Inviting participation from a community through a request for materials did a few key things for my work: it activated a social interaction with people unknown to me (and often unfamiliar with art), while creating an audience invested in the exhibition. It also meant that the museum or other commissioning venue would facilitate material acquisition and become an active part of my art making. This collaboration allows individuals to share personal stories behind the objects that they donate, generating a richer narrative around the work.”

As I received bags of fabric, old Kurdish dresses, and rugs from the community in Nashville, it was recognizable which fabric was from Kurdistan and which fabric was from Joann’s or Walmart. Most of the rugs I collected are not “traditional” or handmade, they are industrially manufactured. I thought both are equally important. Making a home away from home results in a lot of settling for what is around you. Making the dress out of what you can. Adapting and improvisation. I think improv is an important part of my life and practice.

I noticed that a lot of the dresses have mud stains on the bottom of them from being worn at picnics. Some even have makeup stains on the portals where the heads would go through. I found a very special connection to the materials not only from the people who were giving me their old dresses but to the people who made them that I have never even met. This different kind of collaboration happens in the studio when I am working with these dresses, fabrics, and rugs. I start thinking about invisible labor and the tension between the cuts and marks that I make with my hand and the designs that were produced by a software to make them 100% symmetrical.

This blanket won’t keep the dead warm, was a piece I created from the horrific images that were coming out of Rojava (Northeastern Syria) in 2019 during Turkey's “Operation Peace Spring.” The source image itself was from a quick snapshot I took with my phone of the TV screen in my parent’s living room. The TV screen was showing 5 bodies covered in these colorful floral blankets on the ground with people surrounding them. You could find these blankets in almost any MENA household. We all know what they look like and feel like, but don’t know what they are called. I printed that image, and it was on my wall in the studio for weeks. The image is flat. The blanket is soft. The human body is sculptural. Textiles are not flat. Humans are not flat. Human suffering is multidimensional. Receiving images of your people in the homeland suffering is something that is hard to verbalize especially while you are in the comfort of your own home in the west looking at it through multiple screens. There's guilt, helplessness, and privilege involved in these emotions. I have a blanket like that and so do you. A couple of undergraduate students came into my studio and helped me fold the blanket into a triangle. The same way Americans fold a military funeral flag. This blanket like other materials I use is an everyday object. I am interested in pushing and stretching these objects as far as I can to create new meanings and symbols. I cannot look at those blankets the same way again.

Nuveen Barwari, "He reminded me that the flowers in-front of me have a scent too”, old dress, dad's old scarf, thread, 8" x 10", 2021

Nuveen Barwari, The Kurdish dress is my teacher, deconstructed Kurdish dress, latex paint, oil pastel, found wood, 8" x 8", 2021

RB: Have you noticed any surprising similarities or differences in the art/fashion/culture of Nashville, Tennessee and Duhok, Kurdistan?

NB: Nashville is known for its honky-tonks, hot chicken, country music city and waaaaait for it… the largest Kurdish population in the United States. There’s a sharp contrast between the cultures, languages, and fashion which I think is evident in my work. Clashing patterns, languages, materials, and cultures… it’s all there. Tennessee and Kurdistan do have one thing in common and that’s the mountains!

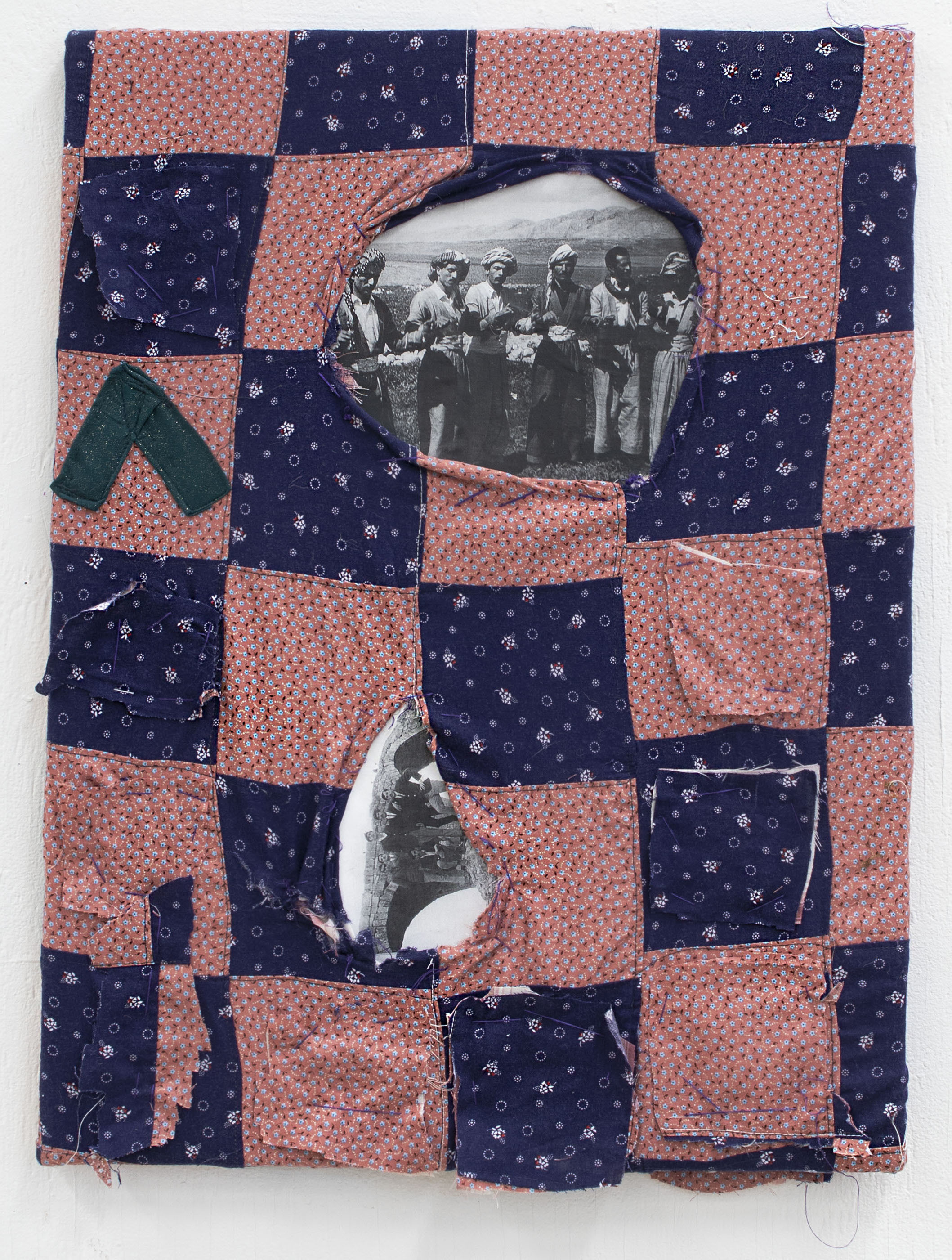

Nuveen Barwari, Back to the land, found fabric, thread, canvas, xerox, 18" x 24", 2021

RB: I assume they inform one another, but do you differentiate your practice between fashion, art and activism?

NB: The t-shirts, the dancing, the conversations I have on the Newave Podcast, the sounds that my teaspoon makes when it hits the teacup, the articles I read, the sumac I cook my food with… they all find their way into my studio in some shape or form. Collages within collages within collages. A bazaar is kind of like a collage. My practice is kind of like a bazaar. You can find so many things at a west Asian bazaar, places of worship, food, community, protests, love, humor, sorrow…

I think there’s an element of urgency in my work that carries throughout my practice… and I believe that has something to do with screen printing t-shirts and protest posters.

Nuveen Barwari, “mala me li ser golekê ye”, found fabric, old t-shirt, found panel, 19" x 20", 2021

RB: In your Cha Cha Cha (2021) video piece, someone off screen aggressively pours tea into cups and saucers sitting on top of a skateboard in front of a curtain of textiles. Can you tell me more about the inspiration behind this piece?

NB:I have been thinking about the concept of “collages within collages” and have been exploring that concept through video and sound. I have some of my fabric collage pieces as the backdrop in this video, the electrical rug skateboard as a stage or table that the teacups are on top of. I collaged images of Saddam Hussein and Ali Hassan al-Majid in court onto some of the teacups that are sitting on the stage/table/skateboard… I made those teacups in undergrad at TSU years ago. According to CNN, Hussein was charged with, “premeditated murder, imprisonment and the deprivation of physical movement, forced deportation and torture”. Ali Hassan al-Majid was known as “Chemical Ali” for his use of chemical weapons against the Kurds in the 1980 genocide campaign that killed thousands of Kurds.

I found this Kurdish progressive political magazine in my father’s archives that was being published in the 1980s that has inspired a lot of my work and this particular piece. It has taught me a lot about political posters, the layering of information in collage, accessibility, humor, sarcasm, and urgency in making these kinds of works. The cover of this specific issue says: “KURDISTAN. CHEMICAL WEAPONS WHY?” It’s a collage on top of what looks to be a page out of a student’s notebook with layers of victims of these chemical attacks, mostly kids, a chalkboard that is instructing students to write an essay about the chemical attack on the Kurds… on the very bottom left corner it says “10/10 good job.” I have another video of the tea pouring aggressively with the sound of my mother’s voice singing to my niece… she’s singing in Kurdish “techa quta babo hat,” which kind of translates to “clap your hands daddy is coming home.” At the end, my mom says, “good job” to my niece… because she probably started clapping her hands. It’s an old song people sing to their kids… but by collaging this audio onto this stage/table/skateboard of teacups it created multiple narratives… it is nauseating when I think about the thousands of Kurds who were forcefully removed and buried in mass graves around the region in which they are still finding mass graves today all over Iraq. The people still don’t know where their relatives are. There is something really nauseating about this piece.

I think about the reports I see pop up on my Twitter feed from following @afrinwomen which tracks the kidnappings and disappearances of women and girls in Turkish-occupied Afrin, Syria today.

Tea is a very intimate thing… I have had some intense conversations that have come up over tea with friends and family. I can go on and on about tea and all the different references I am making, but I’m just going to end this with a piece called “SolidariTEA” by Drost Kokoye that I would love to share with you all:

SolidariTEA

It is part of my Kurdish tradition to serve you chai,

that means tea,

that we gather around the kettle for warmth and therapy,

that you place your burdens on me,

because your struggle is my struggle

your pain is my tragedy.

So, I must look within your burdens

Search in them for the seed,

And pluck it from the root

to rid you of your grief.

Solidarity means you’d do the same for me.

Nuveen Barwari, still from "Cha Cha Cha" 2021

Nuveen Barwari is a visual artist who employs collage to reflect on the fragmented state of diasporic living and membership in a stateless community. Barwari’s expansive practice includes installations; performances; co-hosting a podcast; collecting and repurposing artifacts from her community such as photos, rugs, fabrics, and Kurdish dresses; and an online shop that supplies apparel and art internationally. Barwari received a Bachelor of Science in Studio Art from Tennessee State University in 2019 and is a 2022 MFA candidate at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. Barwari has worked with and completed projects with the Frist Art Museum, Oasis Center’s Art and Activism Series, Coop Gallery, and McGruder Social Practice Artist Residency. She has exhibited in numerous locations such as Kurdistan’s first Fashion Week (2018) in Erbil, Kurdistan region of Iraq, the Frist Art Museum (2019), the University of Michigan (2019), Sugar Gallery (2019) in Fayetteville, Arkansas, Zg Gallery (2020) in Chicago, 21c Museum Hotel (2021) in Nashville, Tennessee, Duhok Gallery (2021) in Duhok, Kurdistan and NGBK Gallery in Berlin Germany (2021). Barwari is represented by The Red Arrow Gallery in Nashville, TN.

Rachel Bubis is a Nashville-based independent arts writer, regular contributor to The Focus blog, and LocateArts.org Web + Print Manager for Tri-Star Arts.

* images courtesy of the artist