INTERVIEW: RAY PADRÓN

FEB. 20, 2019

INTERVIEW: RAY PADRÓN

FEB. 20, 2019

Rachel Bubis: In your artist statement you explain, “My fascination with craft is one of the main driving forces in my research and yet is continually at odds with its distance from my personal history.” Could you elaborate? I assume you wouldn’t describe your own work as craft?

Ray Padrón: Craft is a word that carries a lot of baggage, which is why I use it in my statement. Though I would not describe my work as craft, the histories of the processes I utilize are of significant importance and focus.

Early in my artistic career, I became hyper aware that although I loved learning about these craft traditions, they often felt disconnected or insincere. I would contribute this to my total lack of exposure to those types of processes up to that point in my life. This raised my awareness of a few things; the specificity of my education, my cultural training as a consumer, and an underdeveloped need I had to work with my hands.

Now as I make work, this is the exchange that occurs - I engage in the tradition of these crafts and I deepen my identity as a maker. Though I find this quite satisfying, what compels me even more is this increased awareness of my personal history and my surrounding culture. It is the interaction of these two facets of my work that create a great sense of sincerity and is the main driving force of my practice.

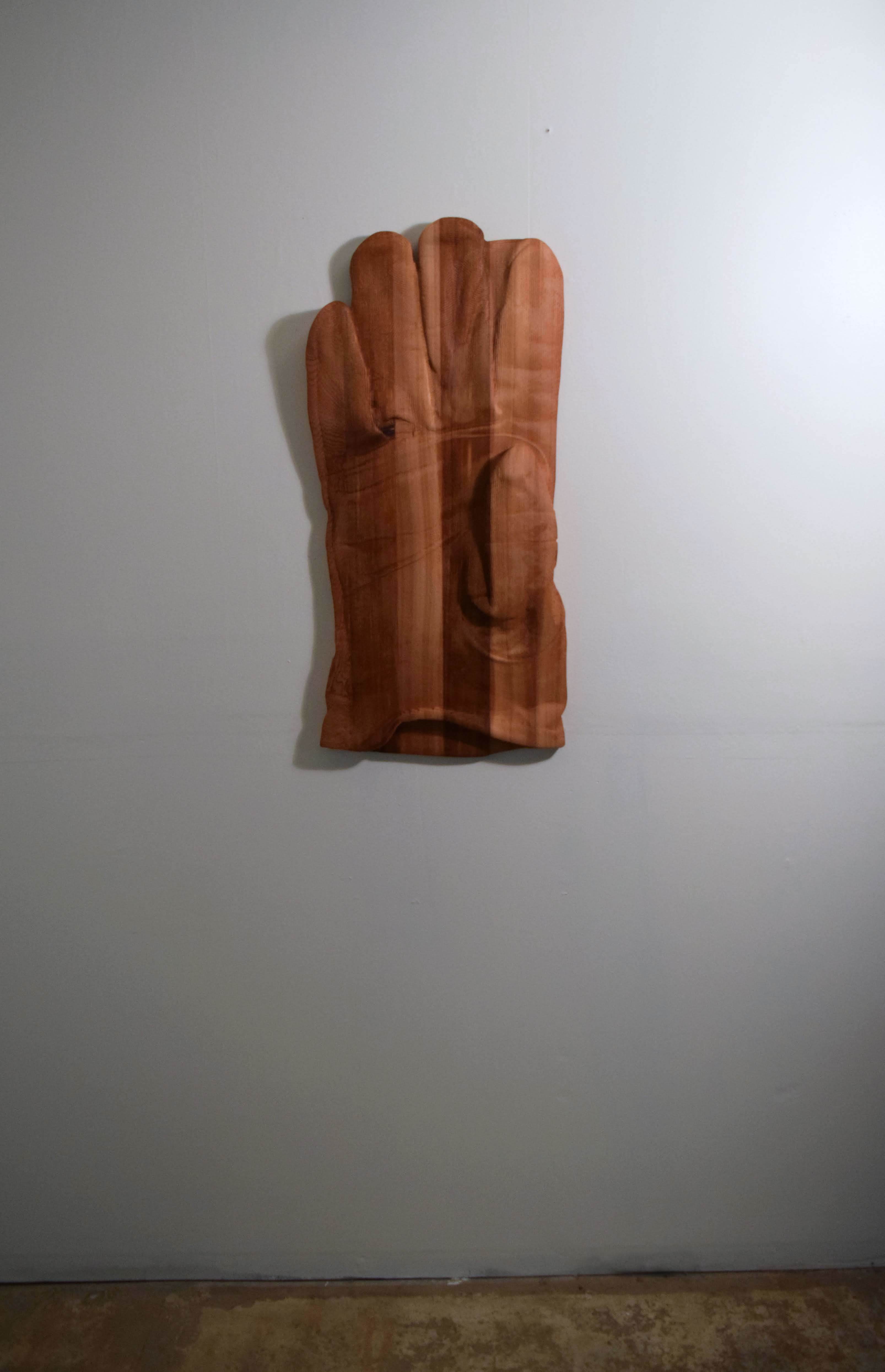

Raymond Padrón, “Roper”, CNC milled cedar, 2018

RB: You chose the word “Journeyman” as the title of your solo show at Pellissippi State Community College in 2014. Would you describe yourself as a “Journeyman”?

RP: A journeyman is a title earned through apprenticeship whom has yet to become a master. Though once widespread, it is now part of a system of education that only exists in certain blue collar trades. I chose the title “Journeyman” partially because it is a role with which I deeply resonate. The journeyman is essentially a person in progress; someone having not just begun, but who has not yet arrived.

I also saw it as fittingly titled since what was once a defined role and path has now mostly dissolved. This echoes my relationship to craft and those feelings of distance and insincerity I mentioned; my journey as an artist had left me unable to see the path back or a clear one forward.

Raymond Padrón, “Manifest Destiny”, fiberglass, body filler, prime

RB: How does the religious iconography in your work relate to your personal history?

RP: In many ways, my engagement of religious iconography functions very similarly to my engagement of craft. I am fascinated by the beauty of these objects, yet struggle to receive them as honest or relevant representations of a spiritual power. I want to break these forms apart, and rebuild them in a fashion that acknowledges the complexity, uncertainty, and sometimes conflicted state of being that contemporary life often brings. It’s important to emphasize that my improvisations on these forms is in pursuit of sincerity, and without a deep rooted tradition in which to engage, they would become formless. This relationship between tradition and improvisation has become essential to my artistic practice and my spiritual journey.

Raymond Padrón, “Rope Separator”, UV print on plywood, 2016

RB: Can you tell me more about your process? Do you make sketches? How much planning vs. improv do you do in the creation of your work? I notice you use body filler in some of your pieces. What draws you to this material?

RP: I don’t really sketch much but I take a lot of photos and create digital collages. Oftentimes, I will print images out full size when I’m starting to think about scale and moving toward final construction. I like to feel how the size affects the body.

As I work, I stay very open to what a piece needs and love when the unexpected reveals itself. That being said, with my work being as labor intensive as it is, I desire some sense of certainty before I commit.

That certainty can take a while to present itself, and though slow at it, self reflection is a fundamental part of my process. Sincerity is a significant word for me; it’s necessary that the work I make personally matters. This requires a level of investment that can be a bit cumbersome. Over the years, my work has only become more dense and serious. Ideas digest for a long time; I sometimes find myself waiting months for the best solution. Pairing that with a labor intensive process, it can set a pace in my studio that can sometimes feel agonizingly slow.

On a similar note, body filler, for example, can take an enormous amount of time, and as nasty and toxic as it is, would love to never use again. Additionally, it can create a kind of perfection that I have begun to question. More recently, I have been pushing myself to make work that functions how I want it to without needing to be “perfectly crafted.”

Raymond Padrón, “The Watchman”, oxidized white oak, 2018

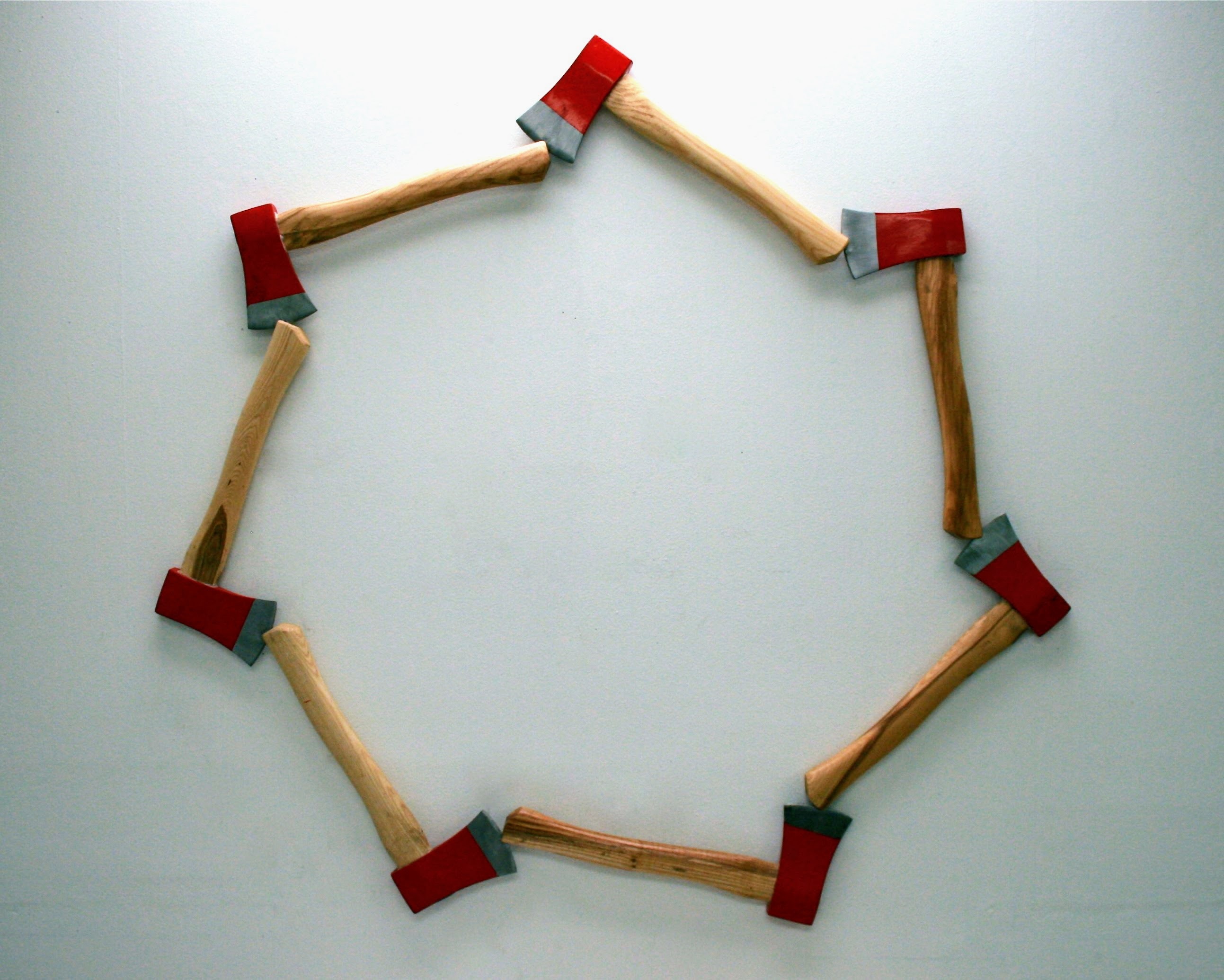

RB: A recurring theme in your work is the creation and use of tools or weapons, particularly axes, that give the impression of artifacts/relics. What interests you about these objects? On a side note, have you noticed axes are very popular right now? I know in Nashville there’s been multiple axe throwing bars and hip artisan axe making companies opening.

RP: Honestly, those boutique axe making companies and axe throwing bars perfectly confirm my interest in tools!

A core part of my artistic identity is in the satisfaction I get by working with my hands. Our hands and bodies are our ultimate tool; while all other tools merely function as an extension. This extension is not simply physical but psychological as well. I see the desire to create, or destroy, or survive reflected in their design. Particularly interesting about the axe is, that while our need of it has become obsolete, a connection remains; it holds something about our identity within it. It’s amusing to think that all those people going to a bar to hurl an axe are longing to tap into that connection. I find the same thing with sports and tools like the baseball bat - essentially, a culturally acceptable context in which to swing a club.

More recently, the use of tools in my work has become a form for improvisation, allowing me to create objects that link their function and purpose with my own personal narrative. This has been a part of my exploration of process as performance.

Raymond Padrón, "Rope Tensioner”, painted wood, 2016

Raymond Padrón, “Fraternity”, modified hatchets, 2016

RB: You describe your studio practice as an “epistemology through craft.” When looking at your Doubting Brontosaurus piece, I’m reminded of the controversy around this dinosaur and how paleontologists have spent the last century insisting that the species and its name are invalid, and yet the Brontosaurus has become such a part of popular culture (i.e. The Flintstones) that it’s not going anywhere. Is epistemology and the history of this dino something you were thinking about with this piece? If so, can you talk more about this? What side do you take on this Brontosaurus issue?!

RP: That piece started with me coming across an enormous, abandoned Brontosaurus statue along a path in downtown Durham, NC. This beautiful and strange sculpture had been around since the 1960’s and had a number of amazing rumors attached to it. One such rumor was that at some point homeless people had punched a hole in its belly and were squatting inside it.

As a child, the Brontosaurus was my favorite dinosaur and when I saw this thing I just fell in love. I started dwelling on the history you mentioned. The Brontosaurus never existed, yet isn’t going anywhere; it holds a place in culture that is outside of its scientific or historical reality.

My thoughts weren’t fully developed until I was reminded of the famous Caravaggio painting, The Incredulity of Saint Thomas.This painting depicts Saint Thomas sticking his finger into the side of Christ in graphic detail. It’s a perfect example of how the physicality of art has such a unique power. Like a wave it hit me that the Brontosaurus could curve his impossibly long neck and penetrate his own side. For me, it’s a deeply personal piece about growing up and questioning your beliefs. Doubting Brontosaurus is an icon of existential questioning; doubting the very nature of its own existence.

Raymond Padrón, “Doubting Brontosaurus”, resin, paint, 2013

RB: You’re the co-founder of a collaborative design and fabrication studio called Range Projects. Your design work can be seen in museums, restaurants, and hotels throughout Tennessee such as 5th and Taylor in Nashville. Does your art practice inform your fabrication work or vice-versa?

RP: Owning a business has had a profound effect on the way I think about my studio practice, and beyond that, who I am as a person. It requires a level of seriousness and diversity of abilities that is unparalleled to anything else I have encountered (maybe beside having a family). As we journey through life and encounter these new roles, it forces us to continually question and reaffirm the importance of our role as an artist. Life often seems to be trying to fill that space with other things. The last six years of owning a business have been filled with working through this tension. I am proud of what has been accomplished and thankful for the gained perspective, but am equally excited to prioritize my studio practice and bring a new level of seriousness and focus to the work I’m making.

Raymond Padrón, “Ball Glove”, oxidized white oak, 2018

RB: What are you working on now and what’s next?

RP: Over the last year I have been working on a series of large scale wood relief carvings that reference the body and specific mentors in my life. They hang collapsed against the wall. The most recent of these, I milled using a CNC router. In addition to the CNC milling, I’ve also been exploring Photogrammetric Processing, a system of turning photographs into usable 3D models. As for what’s next, I have a solo exhibition coming up in May and am eager to have some larger, more substantial works on deck.

Raymond Padrón, “Roper” (detail), CNC milled cedar, 2018

Raymond Padrón grew up in the Northern Virginia suburbs of DC. In 2005 after receiving his B.A. in sculpture and graphic design from Messiah College in Grantham, PA, he moved south to the city of Chattanooga, TN. During his time in Chattanooga he and exhibited in both public sculpture exhibitions and gallery shows across the Southeast. In 2011 he received his M.F.A. from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He has since returned to Chattanooga where he now makes art, exhibits nationally, teaches art, and is co-founder of a collaborative design and fabrication studio called Range Projects.

Rachel Bubis is an independent arts writer as well as the Exhibitions Manager of Seed Space in Nashville, TN.

Ray has an upcoming solo show at the John C. Hutcheson Gallery at Lipscomb University (Nashville, TN) from May 13 — August 2, 2019.

* all images courtesy of the artist