INTERVIEW: SARAH PHYLLIS SMITH

APR. 20, 2017

INTERVIEW: SARAH PHYLLIS SMITH

APR. 20, 2017

Rachel Bubis: Your work explores the nature of photography as a medium, specifically, its “failure due to an inherent nostalgia.” Can you talk more about this?

Sarah Phyllis Smith: At the heart of it I think I’m interested in our relationship to photographic images, and that’s mostly in reference to personal photographs. Why do we feel compelled to take the photos that we do and what happens in us that makes us reach for our cameras and decide that something should or needs to be photographed?

Photos are made as a way to create a historical record that can then be reflected on in the future. I think when I talk about the failure of photography lying in its nostalgia, I’m really thinking about how inefficient photographs are at capturing those moments or places or people that we’re constantly taking photos of. They end up being paper fragments that through time lose context. I think that’s even more present now with how many images never even leave our phones or computers. The prints people are having made at the drugstore may fade before their owner even reaches old age. I think photographs want to promise us something very permanent and we also expect that from them but in reality, the very invention of photography proves that no, we can’t stop time, we can only pull out small moments and make documents that can allude to history but never is that history. So as much time as I spend thinking about how we live with and make these personal images and sometimes how futile that task may be, I can’t not also do it myself. I take photos with my phone all the time, and when I get that alert that my storage is full, I do the same thing that everyone else does and I start deleting things, sometimes deleting something that, at the time, felt important but in retrospect wasn’t. I have family photos that I love dearly and looking at them is both wonderful and a little sad at the same time.

I have a body of work called “I Can’t Love Nobody Else But You” and that title came from a time when I was teaching in Murray, Kentucky and only country music or evangelist radio would come through on the radio. I’m not a fan of country music, but I listened and heard how desperate and lovesick some of those musicians were. I started thinking about love songs in relationship to my photographs and had this idea that they could be one in the same. The way that I feel when I look at photos of my family, or places I’ve been with friends or partners who are no longer in my life, has some of that same melancholy that maybe listening to breakup songs can have. So in that way I think many of my images are a little sad but mostly to me they feel very quiet. My Niagara Falls work is about how we take photos when we’re on vacation. Vacation photos are a special kind of image that speak to such a specific place and experience but afterwards they all kind of look the same and aren’t ever that fun to look at unless they’re your own. For this work, I pushed my way through the crowds to take the same photos the other tourists were taking and made a record of my personal and also very intimate experience of being on vacation at Niagara Falls. It’s funny how much romance is embedded in the culture surrounding the falls that even when my partner and I posted a few photos to social media, some friends thought we’d gotten married just because we were on vacation there. My new work is really focused on making personal images that can hold very specific narratives of place and time but on the surface are entirely anonymous. I think photographs are really good at doing both of those things at the same time.

RB: There’s of course been a lot written on the medium of photography throughout art history. Are you inspired by any specific theories put forth by art historians/philosophers?

SPS: As a graduate student, I read a lot of Lucy Lippard. She wasn’t writing exclusively about photography but her ideas about the landscape and the different ways that we lay ownership over it resonated with the work I was making at the time. There really has been so much written about photography and I think that’s in part because it’s this thing that has embedded itself in every aspect of our lives. In the classroom I talk to my students about how many photographs they interact with on a daily basis and it’s overwhelming. Whether we like it or not, everyone has had their picture taken and at some point everyone has been the one taking it.

My own work sometimes looks at the pain that comes from viewing photographs and an easy person to point to for that is Roland Barthes with “Camera Lucida”. It’s classic photo theory, but much more personal than other things you might read about the medium. Written after the death of his mother, he starts looking at every photograph like it’s a memorial. He describes both the mental and physical pain he experienced when viewing images of his mother and even though she was in the images it wasn’t really her. It’s a strange book that, outside of “On Photography,” [Editors note: by Susan Sontag] is one of the most read texts about photography. It doesn’t really offer up many answers but it’s a text I love and have returned to many times throughout my career.

RB: You touched on this a bit before, but do you have any more thoughts on how technology has affected the medium or how it’s used as a tool at the intersection of art/politics/branding? Do you see it going anywhere different in the future?

SPS: Technology has almost completely democratized photography and that’s pretty incredible and can’t be said for most other mediums. Whether you’re the maker of images or not, social media and the ease of producing photographic images have made it possible for everyone to be a witness from all corners of the globe. Yes, it is legal for you to photograph police. We should be recording the world and holding those who would look to take advantage of us accountable for their actions. Photography is incredibly political. Most of what we know about the history of the world has been written and recorded by a select few but when everyone can document their community, their city, their neighbors, we can begin to see a new and significantly more full record of history forming. Without photography would we still be talking about Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, or Eric Garner? Photography and its availability has changed everything, and will continue to create change as it continues to permeate culture. My own work doesn’t reflect my political interests or affiliations, but I want everyone to be a photographer. We probably don’t need anymore wedding photographers, but right now we do need our world to be recorded, and as a photographic educator, I get a lot of pleasure from sending students into the world not just as experienced image producers, but also educated image consumers.

RB: What is your artistic process?

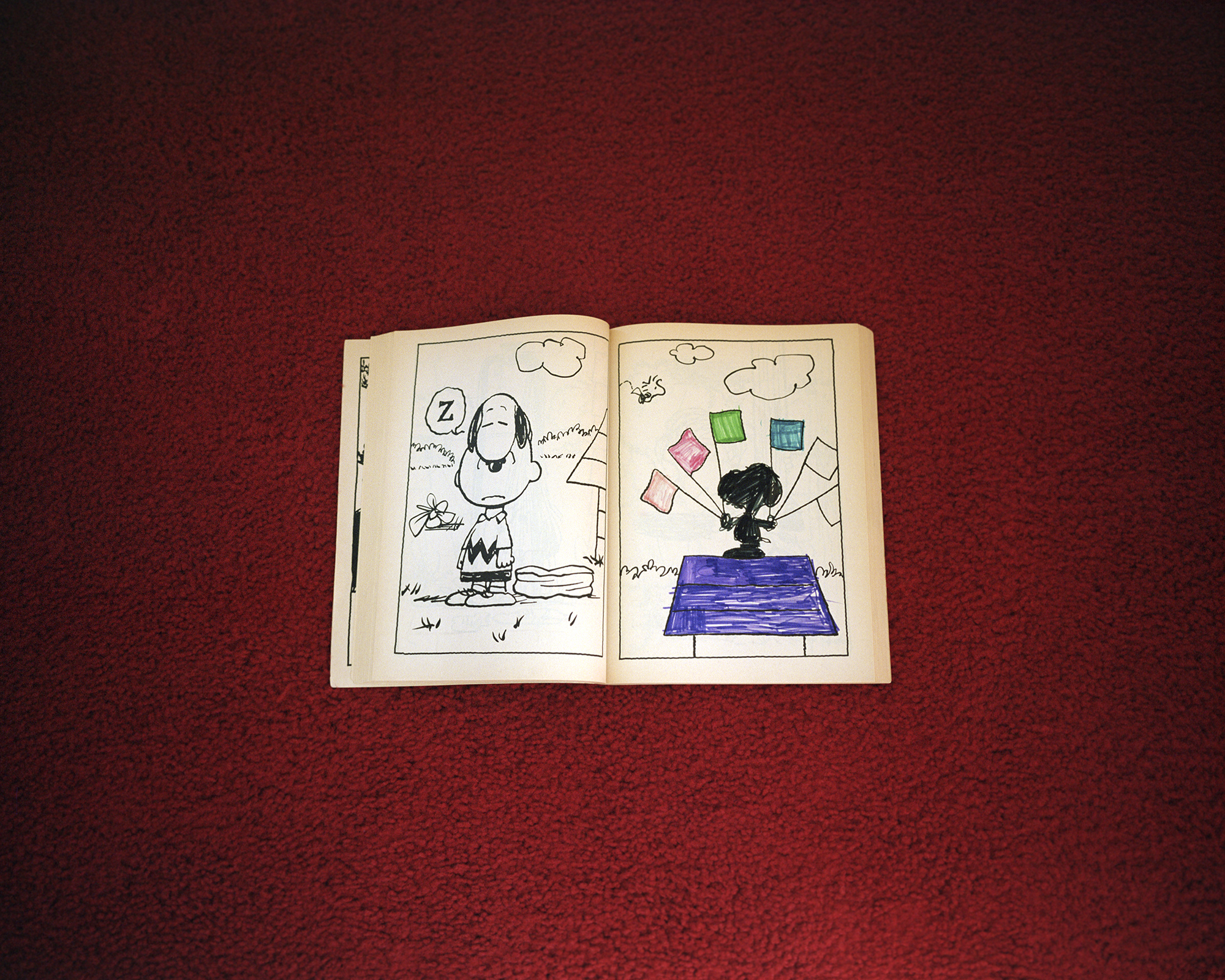

SPS: If my studio practice is anything, it’s slow. I shoot for months at a time, then I’ll send all of my film to the lab for processing. What that process does is it allows me to see connections between images that on the surface may not have anything to do with each other. I can find moments where images begin to speak to each other despite being taken months apart and in opposite parts of the country. It might be something formal, or compositional, that makes me start seeing a connection, but often it’s because I’ll find similarities in my approach to describing completely different subject matter. If I saw my images right after I shot them, I don’t think I could have that same experience. Sometimes images are staged but most are not. My studio contains a collection of objects and ephemera that I sometimes make photographs of, and those are usually the only ones that are ever staged. So much of my work has always been tied to location, and specifically locations that I have strong relationships with so I travel quite a bit. I’ve been shooting with a medium format film camera for many years now but my most recent acquisition is a Mamiya 7ii and that has become my go-to camera. I’m a one woman show, doing all of the scanning, editing, and printing myself. Dust correcting images is the bane of my existence but I wouldn’t have it any other way.

RB: What’s the story behind Bistineau (2016) (the photograph of the deer head in a plastic bag)?

SPS: The head is from a deer that my partner’s brother shot on Christmas. I grew up with a father that hunted but it’s been a long time since I’ve been around it. I don’t really know the appropriate language to talk about it but because the deer was shot on a holiday they needed to do all of the skinning and quartering of the deer themselves. It was a weird moment, but I found myself as an adult standing over this dead deer and feeling just the same way I did as I child when my father would bring a deer home in the back of his truck. In many of my images, I’m looking for moments where the past, present, and sometimes maybe even the future, are present in the image.

RB: Are most of your photographs autobiographical?

SPS: Many of my photographs come from autobiographical experiences, but I don’t want them to end there because otherwise I’m just navel-gazing. I think many of the images read on several different levels and some of that comes through how I group them in exhibitions. I see myself as a curator of my own images, being able to say different things with the work based on what images I show and what images I leave out.

RB: Do you draw a line between your use of photography as an artistic medium and for personal documentation/social media?

SPS: That line gets pretty blurry when the work feels very autobiographical. There are times when I have what I like to call my “real” camera, which is my Mamiya, and that can sometimes really dictate what I can and can’t do when I’m taking a photograph. I use my cellphone like a sketchbook. I’ll often see something that isn’t photographable at the moment but could be at a later date or an arrangement of objects that I like but want to recreate later. I take a lot of pictures through airplane windows, as does everyone else. I have this really grand project in mind that involves aerial photos but I haven’t made much progress yet.

RB: Have you always taken a lot of pictures?

SPS: When I was in middle school, my mother signed me up for some photo classes at a local community art center and that’s where I first learned how to process film and print images in the darkroom. In our family albums there is a picture of our cat playing on the floor with a lobster. For years I returned to that image because I loved it and it always made me feel a little tickled. I still feel that way when I look at it. I think I’ve always really appreciated looking at pictures more than being the one taking them. Growing up, I loved looking at pictures of my parents when they were younger and thinking about who they were in those photos as opposed to the person that I knew them to be. A lot of the decisions that I make with my own work comes from my early interest in looking at my family’s personal photographs.

RB: I know you have an upcoming solo exhibition at The Shed Space in Brooklyn. Can you tell me a more about that show, what you’re working on now, and what’s next?

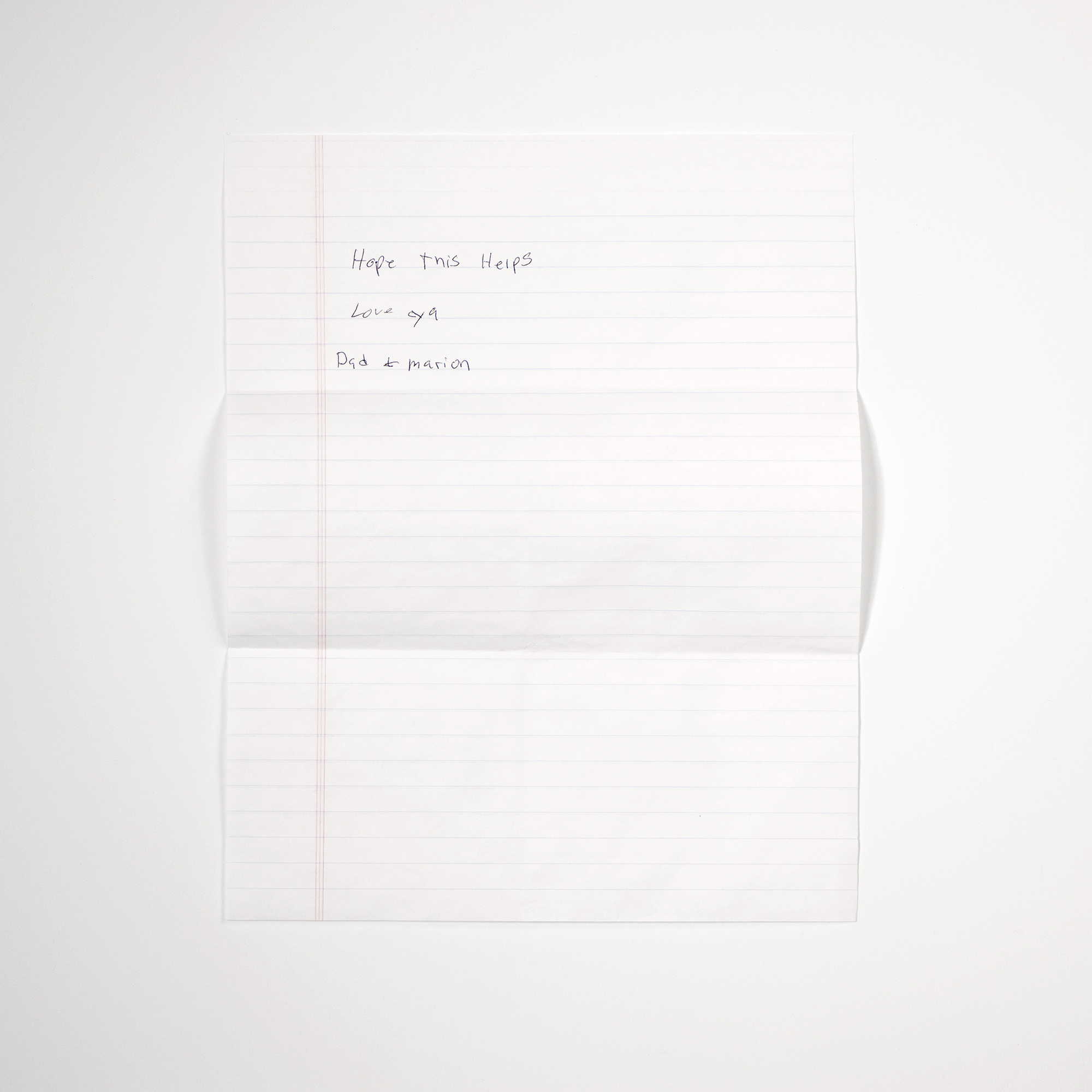

SPS: I’m really excited about the show at The Shed Space. It’ll be the first time I’m showing the Niagara Falls work so I can’t wait to see it all come together. The woman who runs the space, Roberta Bonisson, is incredibly supportive of emerging artists and actively works to give opportunities to people to show work that hasn’t been exhibited yet. The future is open right now. I’m in between projects and playing around with a few things but still at a place where I’m deciding what I want to focus on. I’m always shooting but as I said earlier, the process is slow, and sometimes things don’t feel fleshed out until months down the road. The Niagara Falls work was a real departure from the way that I usually work and I really want to return to that. I also recently lost a grandparent who I was very close with and have a short film that I had been making about him that really needs some attention so the next big thing that I think I’ll finish will be that.

Originally from Middletown, New York, Sarah Phyllis Smith received a MFA from the University of Iowa in 2013 and a BFA from Murray State University. Her recent solo and two-person exhibitions include, I Can’t Love Nobody Else But You at Penn State Altoona’s Sheetz Gallery and An Island is Unreliable at the Janice Mason Art Museum. Her work has been included in various group exhibitions including Art Helix in Brooklyn, Roman Susan Gallery in Chicago, and the Los Angeles Center for Digital Art. Her short film “Everything is Here” was recently screened at Torch Cinema Outdoors at TROOST in Brooklyn, NY. In 2017 she will be showing new work in a solo exhibition at The Shed Space in Brooklyn, NY. Sarah currently lives in Tennessee where she teaches at the University of Tennessee Chattanooga.

Rachel Bubis is an independent arts writer and Curator of Seed Space in Nashville, TN.