INTERVIEW: KATIE HARGRAVE

JUN. 02, 2016

INTERVIEW: KATIE HARGRAVE

JUN. 02, 2016

Jodi Hays: I love this sentiment your mention in your writing -- “we can complicate and unpack the narratives of everyday life”. Can you name an everyday life narrative that you are most interested in this season?

Katie Hargrave: Right now I am interested in exploring the conversation in our culture surrounding the learning and teaching process. I am a teacher (I teach first year foundations at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga), and I am fascinated by the ways in which folks who do not work in education engage in informal teaching and learning (or don’t). With my collaborator Brett Hunter, I have begun a new collaborative duo we’re calling “Like Riding a Bicycle” which explores the freedom and fear around education in our society. This seems particularly pertinent in Tennessee, which has some of the worst public education in the US but some really interesting informal educational opportunities (like the history of the Highlander Center, for instance). I think that exploring narratives of everyday life is inherently political, and empowering individuals to become both teachers and learners outside of the formal educational system is no different. Just think about the power educational systems have.

J: I'd love to hear more on this-like some of the freedoms and fears in education?

K; I think about how to help students learn how to think, how to express themselves, and most importantly learn how to learn. The students I work with had a very different K-12 experience than most of their faculty (hello No Child Left Behind) and as a result they are really hungry for the answer. They struggle when I tell them from the beginning that I will not, under any circumstances, tell them what to do. I have 10+ years more experience than them at looking at and making art, but do not think people learn by being told what is right. Instead, I try to help them work it out.

My favorite educational theorist is Paulo Freire (everyone should read “Pedagogy of the Oppressed”, particularly those teaching in areas with bad public education and race/class conflict). Freire promotes working against a “banking” method of education—where experts deposit knowledge into students—and instead working to get students to see why education matters for them, why education can be liberatory. I also think it is important to remember that most learning happens outside of formalized spaces of education. Where do I learn? When I notice what kinds of plants grow along roadways after construction. When I watch my mother as she tastes a sauce and adjusts seasoning. When I listen to the bartender explain different beers. When we forget that these opportunities for learning are teaching us, we alienate our everyday experiences from learning (and I think devalue it as a society to the point that children hate learning). I think many adults are afraid to admit they don’t know things and forget about what learning really looks like, how vulnerable you feel when learning something new, but also how exciting and how freeing it can be when you have accomplished a learning goal.

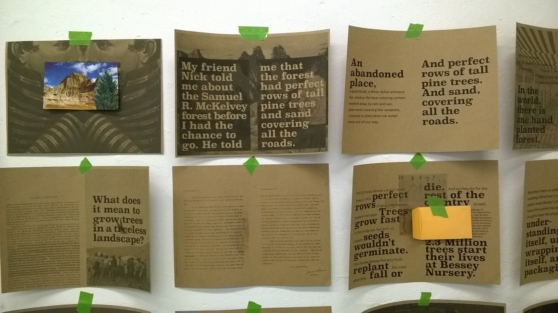

My project with Brett Hunter, “Like Riding a Bicycle”, is about reflecting on a moment of learning / teaching many of us went through as a way to begin to look at other moments of learning. We are creating skill shares, how-to zine libraries, and recording stories about how people learn and teach.

J: Can you talk a bit more about the ambivalence you felt when making formal work as related to "political" subject matter (beet sugar work)?

K: I am not a craftsman. I don’t have a lot of skill with any one medium, and as such the form often feels like a tool used to illustrate content, to make space for content to come forth. Since I don’t think in a primary medium (you referred to this tendency in my work as “Post Studio”), I worried that beginning to come to some mastery, or to make something that looks visually interesting veiled the content too deeply. I try to use established cultural forms and found objects as a way to allow the content to be close to the viewer, and in the case of “In poor tastes good” the content was harder to get at. One way of making is certainly not better than another, but it is a point of tension in my own work.

J: What does an MA in “cultural production” look like, particularly in Boston (I was there 1998-2005, subtext: are you a Red Sox Fan)?

K: Definitely not a Red Sox Fan, no no no (I’m from Chicago, so if anything I have a place in my heart for the Cubs, but the only player I know is Sammy Sosa, which is like ten or more years ago). Cultural Production was an interdisciplinary MA program at Brandeis University. I was attracted to it because it brought historians, anthropologists, museum professionals, archivists, and artists together. As an artist who uses the tools of many other disciplines in incorrect ways, I felt like I had a lot to learn from that proximity. The program is now defunct, but it was a great place to learn about the complexity of cultural narratives, for instance, it is almost impossible to have a real conversation about Israel Palestine at an institution started by Zionists, even when there are Palestinian students and faculty at Brandeis. I learned so much there, mostly how to break the rules and how to read theory, but it was important for me to go and get an MFA in a community of artists after working with humanities and social science folks for several years. After I finished, I studied at the University of Iowa for my MFA.

J: You write on your site, about your project “In Poor Tastes Good” examining an abolitionist-ed effort to support beet sugar: “Between metaphor and formalism, between social practice and interactivity, this project pushes the boundaries of my practice while the subject’s boundaries are almost limitless.” Given our current climate post-Trayvon, etc, have you continued this limitless subject?

K: Right now I am taking a break from sugar for other projects, for two reasons. First, I moved from a place where alternative sugars could be easily grown and that the reasons alt-sugars were produced were political. Second, “In Poor Tastes Good” was a challenge for me, because I used social practice methods in the research phase but I ended up making pretty formal sculptural and video works. I struggle to figure out how political content and formal qualities work together, and I have always struggled with this (this is why I like to surround myself with painters, who are so good at manipulating how content and image work together).

J: Since your practice is decidedly “post studio” (even Post-post studio), do you have any rituals that get you into a work mindset for each potentially disparate project, or are projects disparate, in your mind?

K: I am currently at a residency at Vermont Studio Center, where the post-studio dimension of my work feels particularly acute (like what do I do in this white room?). I read a lot, make a lot of lists, and make a lot of mistakes before something ever takes physical form. The real work is to ask: “what is my research question, and what form will support exploring those questions most?” The work is slow to start (maybe slower than for traditional studio-based artists) but I make a lot of work quickly once it starts to come together. I also collaborate a lot, which helps.

J: What would you be if you did not become an artist (or were not one to begin with?)

As a kid I don’t remember being interested in anything other than art. As an adult, I worked on a farm and apple orchard and loved it, and I worked in libraries and archives for over ten years, so I suppose one of those (very different) fields. I doubt a career change anytime soon.

J: What are you reading?

K: Oh! That is a good question! I am currently reading “Table of Contents” by John McPhee. I love McPhee, and it is the perfect book for being in Vermont on an artist residency. A friend just saw a black bear not far from the residency, and the whole first part of the book is about black bears! McPhee has a great way of telling me all about science and history and culture alongside really interesting personalities. I cannot get enough of him. I also just read a book of poems about the landscape by a fellow resident: “Systems of Ghosts” by Lindsay Tigue.

* All images courtesy of the artist.

Katie Hargrave (b. 1985 Chicago, resides Chattanooga, TN) is interested in the production of American identity through politics, history, mythology, and narrative. Her work elevates stories from popular culture, those hidden in the archives, and the everyday conversations from passerby’s and participants. Hargrave is a professor of art at the University of Tennessee Chattanooga. She received her MFA in Intermedia and Drawing from the University of Iowa, MA from Brandeis University, and BFA from the University of Illinois. Her work has been shown at Proof Gallery in Boston; Gallerie Analix in Geneva, Switzerland; the Manifesta Biennial in Murcia, Spain; The Philadelphia Art Alliance, and the Athens Institute of Contemporary Art, to name a few.

Jodi Hays is a painter based in Nashville. Her works are included in collections of the J. Crew Company (NY), Nashville International Airport, Gordon College (MA) and the Tennessee State Museum, among others. Residencies include The Cooper Union School of Art, The National Parks of America, and Vermont Studio Center. She was a founding member of COOP Curatorial Collective and maintains a studio and pop-up gallery (DADU) in Five Points, East Nashville, TN. She received her MFA from Vermont College, her BFA from The University of Tennessee, and studied Foundations at School of Visual Arts (SVA).