INTERVIEW: JESSICA WOHL

DEC. 01, 2016

INTERVIEW: JESSICA WOHL

DEC. 01, 2016

Note: Jessica Wohl spoke with Eleanor Aldrich four days before the 2016 presidential election at her show "Love Thy Neighbor" at Sewanee's University Art Gallery.

Eleanor Aldrich: Formalism is often thought of as apolitical, where as illustration can border on the didactic- how do you reconcile these in your work?

Jessica Wohl: I was actually an illustration major in college, but as I graduated I instantly began distancing myself from that and realized that the work I was making was much more didactic, so I am pretty conscious about keeping my distance from that side of the scale.

Formalism as apolitical- hmmm.

EA: Or is it?

JW: I do feel like with a lot of work that is strictly formal in that it is graphic or it is very much about color and texture and shape; the makers are making a choice—whether consciously or unconsciously—to not deal with political things. I think a lot of times work like that is made by artists who have the privilege to focus on that with a clear head. Or I would argue that these issues may not be effecting them directly, in the way that an artist who is suffering more politically or socially may be compelled to express themselves based on their experience.

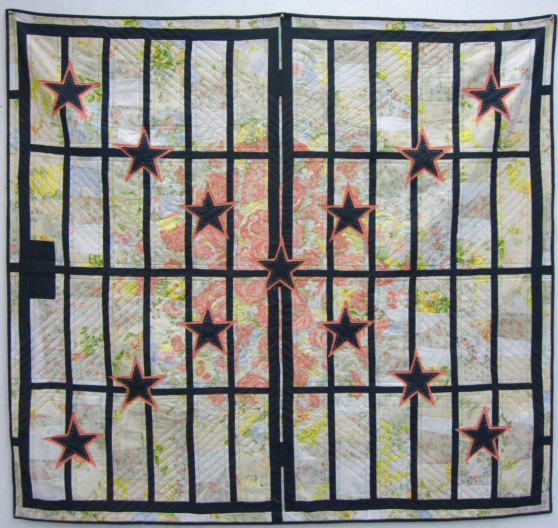

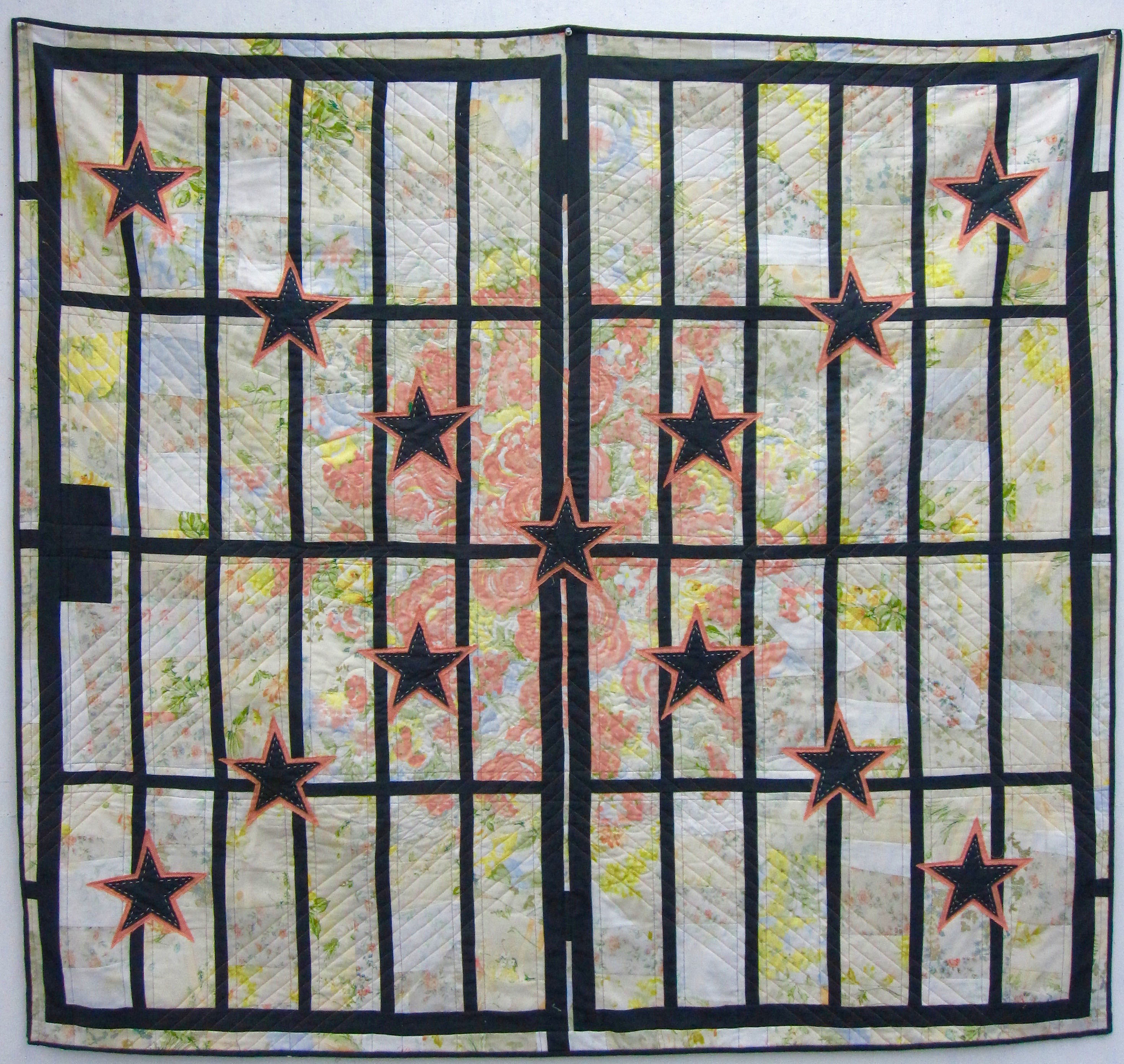

With this work, I hope it doesn’t come off as too illustrative, but I think I am somewhere in the middle where I have the luxury of navigating the world in such a way that a lot of the things I am making work about don’t effect me personally on a day-to-day basis. They do affect people in my family, but I also care very deeply about these issues and in this work I am trying (sometimes in subtle ways) to acknowledge my specific voice, experience, and position that I do see as being privileged. I guess I want to come out and own that in a sense, and not try to hide it or be ashamed of it.

A lot of the work, like the embroidery—the cursive—speaks to the idea that historically, embroidery is a technique that tends to be excessive or embellishment; something that is not necessary for function. But the way many different communities have used quilt-making in the past functioned as a way to salvage fabrics and textiles which were scarce, so they had to save everything they had.

EA: Like the Gee’s Bend’s quilts?

JW: Exactly. These are building on that tradition but I am certainly acknowledging a certain history of excess. I wouldn’t say I come from an extremely wealthy background or anything, but I definitely want that voice to come out: I am a white woman, I grew up in the suburbs of Minneapolis, this is just who I am, and I don’t feel like I need to apologize for it, but I feel like it is really important to acknowledge that that’s the place I am coming from- if I want my work to be genuine, which is one of the most important things to me.

EA: It seems like there are different narrative voices in the show – as the viewer we are sometimes behind the bars looking out, and sometimes we are on one side of the fence, or the text is addressed directly to us. Can you talk more about the role of text?

JW: The first piece I made was We Shouldn’t Have to Live This Way and it initially said “You shouldn’t have to live this way”. That was the first iteration, but I realized the voice of me saying that put me against the viewer in a way that I intended to be empathetic but actually came across as more accusatory than I wanted- almost more like an insult. And so that is why the text reads “we”, because I want to include myself in these issues- it is not something that is separate from me.

Again with the embroidered cursive- when the viewer looks at it I think it comes across as feminine; as a rather contemporary form of calligraphy that can contextualize the time I am saying it, and what my background might be. Historically it was really only middle to upper-class people who were embroidering. I took an embroidery workshop a couple years ago, and there were only white women in my class. The workshop was extremely expensive to attend, and in that entire school there were no people of color. There were all these wealthy white people learning crafts, and that's what I want this voice to conjure up. I had the privilege of time to take the class to learn how to do this. I didn’t just hand write this- sewing those words takes hours! And it acknowledges that I had the time to do it- to me that is really important.

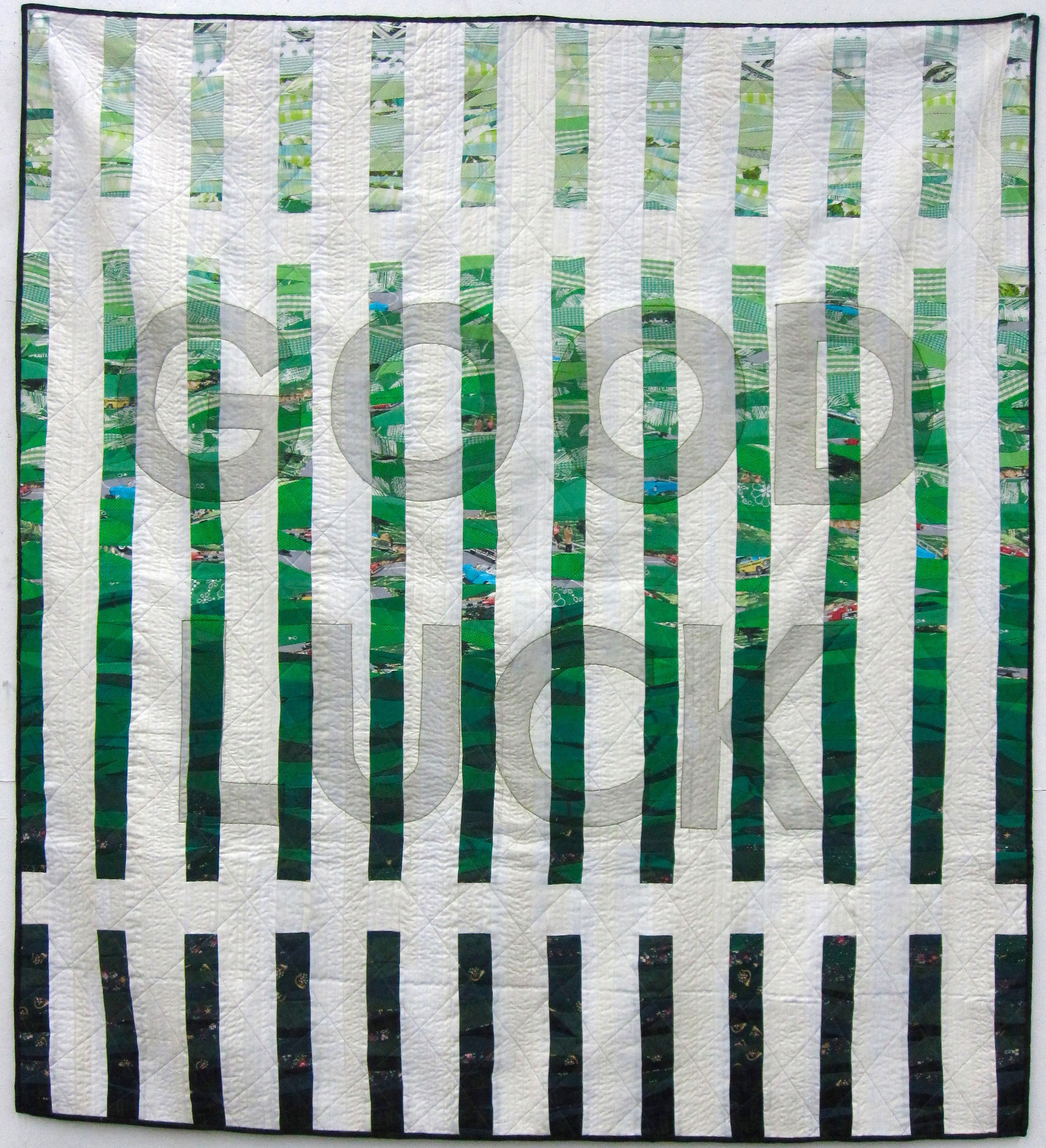

The bigger block letters, to me, almost come from an omniscient voice that seems as if the universe or the-powers-that-be are speaking. That is why I wanted to use a more generic, timeless font. There is a little bit of sarcasm- like in “Good Luck”- that one is pretty snarky and aggressive- it could be interpreted as being a well wish- depending on who you are. If you are one of the little white suburban people from the 50s, literally depicted in the fabric of the quilt, conquering the landscape as you build your suburban home, then good luck means good luck. It means good luck with your life and accomplishing this American Dream, but to everybody else, good luck getting there. I feel that sentiment, but it is not necessarily my voice.

The text “Shut Up and Listen” in the piece White America is my voice. It is me yelling. It is me acknowledging that I get angry and that I get mad and that sometimes I just want to yell that at people. But I don’t and I won’t. The word “listen” is in that feminine voice, a softer more empathetic voice. This piece is more about me not being able to reconcile the things I feel positive about and the things I feel more worried about. I want to feel hopeful, but I’m still quite frustrated- I hope that comes across in the text, and in the font.

EA: I think the title White America is helpful in understanding who the speaker is and who the audience is for that one. Can you talk some about how that one in particular came into being?

JW: Yeah- this is the last piece I finished. Before I made it, I put all of the other quilts up on a wall together and felt they were just too sweet. It didn’t get across the real anger and despair and hopelessness that really fueled all of this. So it was a piece I made because I had to give the exhibition some kind of punch- I had to show that I am angry- and somehow convey that while I think there is a lot of beauty and positivity that is happening right now, there are some things that are really in distress- which is why I used the symbol of the upside down flag. I felt like I had to acknowledge that pain somewhere; everything else was just too quiet.

EA: Quilts and quilting are largely marginalized as a female art form – is there something overly essentialist and gendered about assigning that comforting role and the uniting role to quilts and thereby femininity?

JW: I found out I was pregnant a week before I started my sabbatical to go and begin this project, and I finished when my son was probably six weeks old- so there is something that I couldn’t escape about knowing that all this work and a person were created by me at once. There is obviously something very motherly or maybe tender or nurturing in wanting to create some kind of softness around an issue or a person- it might all be connected, but I haven’t worked all that out yet- it is still too new.

It is very possible that there is a next chapter to the lives of these quilts that might be a little bit more socially engaged. There’s a part of me that considered that they may need to go and live with families for a while, and then other families for a while- hanging on a wall isn’t all they are meant to do. I don’t know what the next step is yet but it is possible it may have more of a physical impact. Conceptually, the reason I chose a quilt is because it can get people together and comfort them and warm them up and they can snuggle with it, and feel something warm and cocoon themselves into this little safe-haven. That might help somebody who is in pain- even if it is just sitting with somebody they love. Maybe there is a way of bringing people together who don’t even know each other. I think there are ways that the quilts can make a difference but for now I definitely am at peace with the fact that they may not do anything- I am just doing what I can do, like sending thoughts and prayers to someone in pain.

EA: I think that is interesting- having a social practice component to it, but there is always that tension- like is painting not enough? Does it need to go on and do something else?

JW: That’s why I made quilts- as a painter I couldn’t figure out a way to do this with paint. If these were the exact same images, but made of paint on canvas, it would loose so much of that intimacy. I think people can imagine using these as blankets. They don’t have to physically be used for a viewer to understand how it works or imagine them in use. But I couldn’t do that with a painting- painting would just be color and pigment on the support, and that was just too far removed.

EA: It seems like there’s a lot of drawing going on in terms of the seams- I was interested in how you talked in your statement about gerrymandering and redlining and some of these practices that are drawings that have a very real impact on peoples lives.

JW: The quilting itself- meaning the stitches that are joining all three layers together- that is often very intentional. In Good Luck, the quilting is based off of a chain link fence so you have a picket fence and a chain link fence together. The quilting in both

EA: These drawings of people sleeping- did you do them from life?

JW: No, they are based on photographs of people I know. What I want to be seen in them is that all of the people are in a state of repose- they are all of us. Young and old, black and white, male and female. There’s no distinction between their belief systems, there’s no distinction by class, there’s no hierarchy. They were all created the same way. And they are all at peace. At a time when everybody’s experience puts them in a different perspective, I wanted to portray us all as the same.

EA: It is also shared vulnerability.

JW: Absolutely.

* All images courtesy of the artist.

Wohl's solo exhibition, Love Thy Neighbor, is currently on view at the University Art Gallery, The University of the South, Sewanee, TN through January 27, 2017.

Jessica Wohl received her BFA from the Kansas City Art Institute in 2001 and her MFA from the University of Georgia in 2010. Originally trained as an illustrator with specialization in art history, her studio practice now includes drawing, painting, embroidery, quilting, collage, performance and installation.

Wohl’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, recently at the Belfast Photo Festival, the Robert Mann Gallery in New York and the Zeitgeist Gallery in Nashville. Her work has also been exhibited at venues in Miami, Atlanta, Kansas City, England, Finland, Norway, Italy, Hong Kong and Korea, and has recently been featured in Burnaway, Vogue and ArtNews. Her work is collected by the Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, the Sprint-Nextel Corporation, the H&R Block World Headquarters, numerous private collectors and is included in the Drawing Center’s Viewing Program. She is currently an assistant professor of Art at the University of the South where she teaches Drawing and Painting.

Eleanor Aldrich holds an MFA in Painting & Drawing from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, where she currently lives. She was a participant in the Drawing Center’s first Open Sessions and her work has been included in New American Paintings and on Artforum.com. She also has attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine.